By Louis Golino for CoinWeek …..

Girl on the Silver Dollar by Roger W. Burdette (Seneca Mill Press, 2019)

* * *

Ask most collectors of the Morgan silver dollar issued from 1878 to 1921 who the model was for the image of Liberty that appears on the coin’s obverse, and they will likely say it is Anna Willes Williams. Born in 1857, Williams was a Philadelphia schoolteacher at the time, who went by the nickname Nannie.

Her story became legendary not only because Morgan dollars are so popular and widely collected but also because it was the first time a real person was believed to have appeared on an American coin (at least based on press accounts at the time). But according to award-winning numismatic researcher and author Roger W. Burdette in his new book Girl on the Silver Dollar (2019), it is far more probable that Morgan’s Liberty design “was a composite of [Morgan’s] wife, Alice, and ancient Greek designs in French interpretation. If any of Nannie Williams’ features are included in the silver dollar design, it may be more coincidence than anything else (Burdette, 31).”

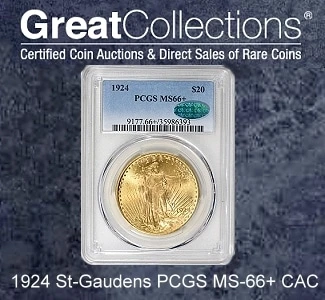

Composite images based on different models, or those that are partly inspired by real models while also reflecting design motifs associated with specific artistic styles or periods, are a staple of American numismatic art – especially in allegorical representations of Liberty. A good example is the Liberty image that appears on the obverse of Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ celebrated $20 gold double eagle that was based on a combination of Greco-Roman motifs and an African-American model from South Carolina named Hettie Anderson, who stood for both Saint-Gaudens and Adolph Weinman.

Burdette says the matter of Williams’ role on the Morgan coin will probably never be fully resolved but lays out a compelling case based on extensive research into her, famous United States Mint designer and engraver George T. Morgan, and the artist Thomas Eakins–for whom Williams also modeled and who introduced her to Morgan–that is based on U.S. Mint and Treasury documents from the National Archives and press accounts and numismatic articles of the era.

He also explains that she did model a number of times for Morgan in 1876 while he was working on the silver dollar obverse but that her actual features and youthful appearance are present not in that design but instead on the famous 1879 School Girl pattern and a half eagle pattern. For example, the chin on the Morgan obverse resembled that of Morgan’s wife, who arrived from England in 1877, rather than that of Ms. Williams.

Moreover, Morgan, who came to the U.S. from England in 1876 after the Royal Mint’s deputy master recommended him to U.S. Mint Director Henry Linderman, had already begun work on a Liberty head silver dollar obverse before arriving in America. He was hired specifically to create the designs for a new silver dollar due to widespread dissatisfaction with the coinage of Charles Barber. Director Linderman wanted a new design for a silver dollar with a “classical head of Liberty” (i.e., one based on Greco-Roman motifs) that might be used on all silver coins except the Trade dollar (Burdette, 10).

Moreover, Morgan, who came to the U.S. from England in 1876 after the Royal Mint’s deputy master recommended him to U.S. Mint Director Henry Linderman, had already begun work on a Liberty head silver dollar obverse before arriving in America. He was hired specifically to create the designs for a new silver dollar due to widespread dissatisfaction with the coinage of Charles Barber. Director Linderman wanted a new design for a silver dollar with a “classical head of Liberty” (i.e., one based on Greco-Roman motifs) that might be used on all silver coins except the Trade dollar (Burdette, 10).

Based on his training that emphasized “copying classical models with a strong emphasis on French interpretation” (Burdette, 12), all of Morgan’s Liberty designs featured “the Grecian nose and forehead which was considered ‘classical beauty’ of the time” (Burdette, 30). But we also know that after Morgan arrived in the U.S., he wanted to give his design a more distinctly American look that reflected the beauty of young American women he saw in Philadelphia.

Numismatic Lore

Given the strong case Burdette makes (buttressed by images of paintings and sketches) that Anna Williams is not the woman on the Morgan dollar, one wonders how the view that she was the model became so widespread that her 1926 obituary devoted far more space to that story than to her important work as an educator. In fact, though she was a kindergarten teacher and education student at the time she modeled for Morgan, Williams would later publish extensively on education and philosophical issues and rose to become the Superintendent of Kindergartens for Philadelphia. Modeling was something she did briefly as a young woman (from 1876 to 1880 or 1881) to supplement her modest income at the time.

The answer to this question lies in shoddy journalism of the time and the fact that inaccurate news stories were often repeated with no critical analysis in numismatic writing of the era, including a famous 1896 Numismatist article called “The Silver Dollar Girl”. That piece referred to Williams’ face as “known to more people than that of any other woman of the American continent” (Ray Levato, “Numismatic Nostalgia: The Girl on the Morgan Dollar,” Coinage, November 2015). In addition, as Burdette notes, as far as can be determined, no numismatic writer ever actually interviewed Williams.

The story of the Morgan dollar girl so familiar to collectors and numismatists for more than 130 years is that Williams was hesitant to model for Morgan because of the conservative social mores of the time and her concern that if it became known that she had modeled, it might jeopardize her teaching career. Thus, she is said to have agreed only on the condition that her identity remain anonymous and that a cover story be used, which is that the inspiration for the design came from a Greek figure Morgan saw at the Philadelphia Academy of Art, where Morgan trained.

An August 13, 1879, a Philadelphia Record newspaper piece said that Williams was the real model for the silver dollar obverse. This story, repeated in many other accounts of the time, took on the force of lore, but it remains unclear whether any of it was based on information from Anna or her friends. Or, as Burdette suggests, it may simply have been invented by reporters to fit the narrative.

It did, however, lead to much unwelcome notoriety for Williams that subsided but never fully went away. She sought to downplay the significance, referring to it later as “an incident of my youth” (Levato, 31) and “a casual and easily forgotten affair” (Burdette, 33). However, according to other press accounts, the incident and publicity surrounding it may also have been a reason why her planned marriage was called off by her fiancé.

It did, however, lead to much unwelcome notoriety for Williams that subsided but never fully went away. She sought to downplay the significance, referring to it later as “an incident of my youth” (Levato, 31) and “a casual and easily forgotten affair” (Burdette, 33). However, according to other press accounts, the incident and publicity surrounding it may also have been a reason why her planned marriage was called off by her fiancé.

It is also ironic that while her modeling for Morgan (which consisted in part of her sitting while reading a book, as seen in an 1876 portrait believed to have been done by painter Thomas Eakins and one of his students) was seen as controversial at the time, Williams also did nude modeling for Eakins. One of the great strengths of Burdette’s book is the use of images of paintings and sketches of or believed to be of Williams, which are compared to the final Morgan design and patterns he created.

Beyond the Coin

Burdette’s research on Williams’ role in the Morgan dollar design takes up roughly the first third of the book. That is followed by additional biographical information on her, focusing mainly on her educational career, and extensive discussion on the origins of the Morgan dollar program; the many classic Liberty head designs considered for it prepared not only by Morgan (especially his 1877 and 1878 half dollar and dollar patterns) but by chief engraver William Barber (especially the “Sailor Head” patterns) and Philadelphia artist Hermann Faber; and the numerous production issues encountered in 1878 — the first year of production that required design modifications such as to the feathers on the reverse and production of new hubs and dies. That is why there are so many major die varieties of the 1878 coin that are part of a complete set of the coins.

Burdette also covers Morgan’s extended frustration at being passed over for the chief engraver position until 1917, when he made improvements to Hermon MacNeil’s Standing Liberty quarter that was used for the first six months of 1917. Then under the Pittman Act that called for the Morgan dollar to be issued again in 1921, he was asked to revise his 1878 design with some modified details and shallower relief. Finally, when the 1921 Peace dollar’s original design became the subject of criticism from the press for its inclusion of a broken sword on the reverse, Morgan was asked to recut the hub and die for the reverse by cutting out the sword.

The final two chapters examine why the key date – the 1895 coin — exists today only in proof despite the fact that 12,000 Mint State coins were struck, and the 1918 Pittman Act that led to the melting of 270,232,722 (Burdette, 133) of Morgan dollars (about half of the entire mintage to date, including perhaps all 12 bags of 1895 coins) with records only of the total number destroyed, not of which dates and mintmarks were melted. This forever created major lacunae in Morgan dollar history that many researchers have sought to address with their estimates of surviving populations of each coin – most notably in the work of Q. David Bowers. The coins were melted in order to sell them as bullion to Great Britain to help stabilize the price of silver. At the time the Germans were trying to weaken Britain by spreading rumors it did not have enough silver, and the silver needed for U.S. coinage was replaced with newly mined American silver.

Greco-Roman vs. American Liberty

Prior to the new book’s release, the main evidence that Anna Williams was not the model for the Morgan dollar came from an undated letter found in a 2002 auction from Morgan’s youngest child, Mrs. Mervyn Graham, to her daughter Charlotte that states: “Father always said no matter how many models they posed for him, that he never bid any and that he just made up the obverse himself (page 9).”

In addition, an August 11, 1879 New York Times article that says Williams’ face appears on the Morgan dollar includes the fact that while “the Grecian nose and delicate lips” were based on her features, “the full rounded chin” was more like that of Morgan’s wife Alice (Burdette, 45) and that by the time Morgan fleshed out the completed design it was not possible to see in it any direct resemblance to Williams.

It is very unfortunate that few writers and researchers over time did not pick up on those important details. However, in his 1971 book Numismatic Art in America, which remains the best volume on the topic, Cornelius Vermeule referenced “the direct conflict between the artist’s own word that a Greco-Roman head provided the model and the apocryphal, romantic legend that a certain young woman was the model for the head of Liberty (Vermeule, 69).”

In addition, this author drew on press reports from the period to explain that the belief that Williams was the model appears to have been rooted in “attributing ‘all-American’ virtues of modesty and milkmaid physique to the girl allegedly the model for the American goddess (Vermeule, 71).”

In other words, the real roots of why this story spread so widely for so long lie in the standards of beauty at the time and the prevalent societal belief that Liberty had to be a woman who was “chaste and beautiful,” (Vermeule, 71) as an 1878 report in the Philadelphia Sunday Republic noted. A modest young schoolteacher fit that bill perfectly.

Burdette’s book — a model for the kind of original numismatic research that can change our understanding of important facets of the hobby — is essential reading for Morgan dollar enthusiasts and anyone interested in the history of American coinage. It is high time that a numismatic researcher has finally uncovered what appears to be the real story about the Morgan dollar design that reveals a lot about American social mores and artistic standards of the late 19th century.

* * *

Louis Golino is an award-winning numismatic journalist and writer, specializing primarily in modern U.S. and world coins. His work has appeared in CoinWeek since 2011. He also currently writes regular features for Coin World, The Numismatist, and CoinUpdate.com, and has been published in Numismatic News, COINage, and FUNTopics, among other coin publications. He has also been widely published on international political, military, and economic issues.

Louis Golino is an award-winning numismatic journalist and writer, specializing primarily in modern U.S. and world coins. His work has appeared in CoinWeek since 2011. He also currently writes regular features for Coin World, The Numismatist, and CoinUpdate.com, and has been published in Numismatic News, COINage, and FUNTopics, among other coin publications. He has also been widely published on international political, military, and economic issues.

In 2015, his CoinWeek.com column “The Coin Analyst” received an award from the Numismatic Literary Guild (NLG) for Best Website Column. In 2017, he received an NLG award for Best Article in a Non-Numismatic Publication with his piece, “Liberty Centennial Designs”.

In October 2018, he received a literary award from the Pennsylvania Association of Numismatists (PAN) for his 2017 article, “Lady Liberty: America’s Enduring Numismatic Motif” that appeared in The Clarion.

I know the concept of beauty at the time Morgan dollars were made may have changed significantly later in the 20th century. I always thought whoever it really is posing as Liberty on the Morgan is one of the least attractive women I’ve ever seen. To me, the model as Liberty on the Peace dollar is a far better representation of both beauty, and Lady Liberty.

It’s the Eurocentric standard of beauty that prevails.