By Tyler Rossi for CoinWeek …..

What does it take for an ancient historian to claim that you died by having molten gold poured down your throat?

Easy – you just need to be the richest Roman to have ever lived. It also helps if you earned your vast fortune through slavery, dubious business dealings, and extorting the poor. Such was the financial legacy of Marcus Licinius Crassus.

Born circa 112 BCE, Crassus belonged to one of Rome’s most influential families. His father, Publius Licinius Crassus, was a general and senator while his ancestor Lucius Licinius Crassus, who served as consul in 95 BCE, was one of Rome’s most influential orators. Despite this privileged background, the young Crassus grew up in a period of extreme political and physical danger – the civil war between Lucius Cornelius Sulla and Gaius Marius. Aged just 24 years old when formal hostilities broke out, Crassus made the fateful decision to back Sulla.

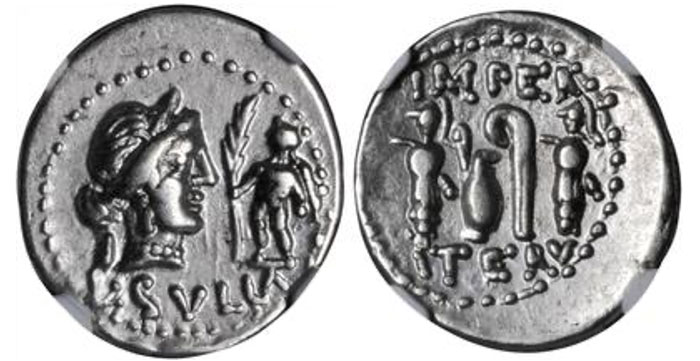

Even in these early years, the young man’s greed could be seen easily. He was able to purchase huge quantities of land at criminally low rates from the estates of influential men that Sulla ordered executed during his many proscriptions. Crassus may have even used some of the newly minted aurei that Sulla began striking at a traveling military mint in the mid-80s BCE. These extremely rare coins were valued at 25 silver denarii and were a much more portable store of wealth, with two different examples shown below. Both aurei depict the dictator Sulla on the reverse, but one shows him driving a quadriga and the second riding a horse.

Crassus’s support of Sulla turned out to be a political blunder since as soon as Marius emerged the victor, the youth was forced to retreat into exile as his father and older brother became victims of the inevitable purge. Once Marius died and Sulla regained power, Crassus was able to return home.

After the Sulla-Marian civil wars ended, Crassus continued to build his already considerable fortune. Using the income from lands he acquired during the wars, he purchased 500 slaves, which he then formed into a firefighting brigade. He would wait for a fire to break out in the crowded and notoriously fire-prone slums of Rome, and then immediately offer to purchase the building and land from the panicked owner before he ordered his slaves to douse the flames.

The historian Plutarch estimated Crassus’s fortune at 7,100 talents or 170 million sesterces at its peak – an amount “roughly equal to Rome’s entire annual revenue” (Cowan). Therefore, since Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great were both desperately in need of cash, he was the man that they turned to when forming the First Triumvirate.

Despite his service in the Sulla-Marian civil wars and during the Third Servile War, the one thing that Crassus did not have was a respectable military career. Thus, armed with the apocryphal quote “A man is not rich unless he can raise an army at his own expense”, the richest man in the world bought himself an army and marched east.

It was in this latest war against the Parthians that Crassus would meet his ignominious fate.

This campaign was started for no other reason than personal glory, and, as Cassius Dio would later write, Crassus “had no complaint to bring against them nor had the war been assigned to him; but he heard that they were exceedingly wealthy and expected that Orodes would be easy to capture”. After a series of strategic blunders, the wealthy general found himself on a plain near an ancient Mesopotamian city named Carrhae, facing the forces of Orodes II, King of Kings of the Parthian Empire.

Finding himself surrounded on all sides in the now-famed double envelopment, Crassus was forced to watch as the Parthian cavalry rode in front of his lines waving the freshly decapitated head of his son Publius. His forces were then quickly overwhelmed and out of an estimated 43,000 Roman soldiers, 20,000 were killed and 10,000 were captured. The battle was a complete humiliation for Rome.

While it is said that Crassus died in the fighting, ancient sources differ in the eventual fate of his earthly remains. Ever dramatic, Cassius Dio records that the Parthian King of Kings ordered molten gold be poured down Crassus’ throat, in order to slake the Roman’s thirst for gold. A different yet no less humiliating fate is detailed by Plutarch, who writes that “they sent his head and hands to Orodes and honored the Roman with a mock triumph” (Hudson, 2019).

This defeat not only affected Rome emotionally but left a very real power vacuum. Without the balancing presence of Crassus to stop Caesar and Pompey from fighting, the First Triumvirate faltered. Eventually, the pair would split and fight another war over the control of Rome.

Interestingly for such a wealthy man, there are very, very few coins that are attributable directly to Crassus. In fact, there are only two that can be definitely attributed to M. Licinius Crassus. The two coins are a variation of the Seleucid emperor Philip I Philadelphus’s tetradrachms and one type of Syrian bronzes minted in Antioch that date to the 12th and 13th years of the Pompeian era (Vagi, 37-8).

After the last Seleucid emperor Philip II Philoromaeus’s death in 56 BCE, the Romans reintroduced his father’s coinage. This silver tetradrachm minted under the proconsul Aulus Gabinius in 53 BCE, the year of Carrhae, displayed the monogram of Crassus to the left of Zeus’s feet on the reverse. While there are no marks on the anonymous bronze issue from Antioch, coins of this type were struck in the same year as the Philip I posthumous tetradrachm. Consequently, this means they were most likely produced by order of Crassus.

There is a third coin that may depict Crassus on the obverse. However, there is some debate as to whether the portrait is actually Crassus or Gabinius. Earlier issues of this type included the legends ΓA or ΓAB, which led numismatists to assume that the figure was that of Gabinius.

Rachel Barkay, of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, argues:

“The portrait on these coins differs from that on coins of Gabinius, and it also lacks an identifying legend. Since the coin was issued during the governorship of Licinius Crassus, it seems likely it bears his portrait as well.”

As is evident by the scarce nature of coins produced by Crassus and his son, not only is it difficult to find examples of these types, but they are usually expensive. The Æ from Decapolis pictured above hammered at $2,100 USD in 2013 and the posthumous Philip I type sells for almost the same amount. Selling for between $200-500, the P. Licinius Crassus denarius is more affordable, and the autonomous Antiochian Æ20 usually sells for $100-200.

* * *

Sources

Cowan – https://ancient-history-blog.mq.edu.au/cityOfRome/Roman-Real-Estate

http://www.columbia.edu/dlc/garland/deweever/C/crassus.htm

https://sites.psu.edu/firsttriumvirate/crassus/

http://classics.mit.edu/Plutarch/crassus.html

https://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/miscellanea/trivia/crassus.html

Hudson – https://www.britannica.com/event/Battle-of-Carrhae

Vagi, David. Coinage and History of the Roman Empire, Vol. 1. 1999

https://www.ngccoin.com/news/article/1839/Coins-of-the-Roman-Republic/

* * *

About the Author

Tyler Rossi is currently a graduate student at Brandeis University’s Heller School of Social Policy and Management and studies Sustainable International Development and Conflict Resolution. Before graduating from American University in Washington D.C., he worked for Save the Children creating and running international development projects. Recently, Tyler returned to the US from living abroad in the Republic of North Macedonia, where he served as a Peace Corps volunteer for three years. Tyler is an avid numismatist and for over a decade has cultivated a deep interest in pre-modern and ancient coinage from around the world. He is a member of the American Numismatic Association (ANA).