By Mike Markowitz for CoinWeek …..

IN BIBLICAL HISTORY and popular legend, Herod “the Great”, Rome’s client king of Judaea from 40 to 4 BCE, is an evil tyrant.

Born about 73 BCE, Herod’s wealthy father Antipater served the Hasmonean kings of Judaea and befriended Julius Caesar, who made Antipater a Roman citizen. Herod and his father were Idumean, a Semitic people recently converted to Judaism. Herod’s mother Cypros was a Nabataean princess. When young Herod was appointed governor of Galilee, his brutality in suppressing bandits got him in trouble with the Temple priesthood in Jerusalem, but his connections saved him.

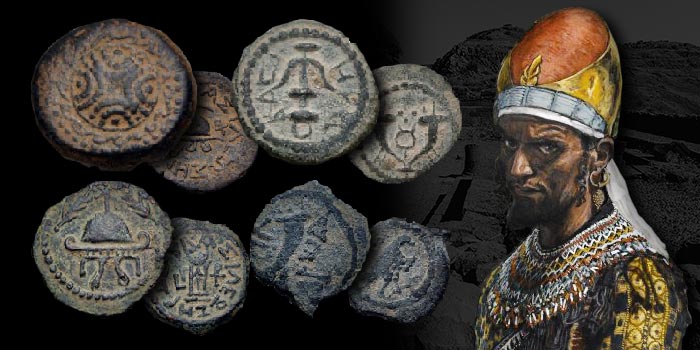

In 40 BCE, Rome’s Senate made Herod king of Judaea. It took him three years to secure control of Jerusalem. Many of his coins are dated “Year Three”, likely commemorating this victory. All Herod’s coins are copper; he leased rich copper mines on Cyprus from Augustus. Some coins were struck at Jerusalem, but most were struck at Sebaste[1], near modern Nablus in Samaria.

Herod’s common coins are popular with collectors of Biblical coinage and are reasonably affordable in average grades.

8 Prutot

Like most ancients, Herod’s coins carry no mark of denomination, but numismatists designate the largest one as 8 prutot[2]. The weight of these token coins was irregular; well-preserved examples range from less than six grams to over 10[3].

The obverse shows a dome-shaped object topped by a star and flanked by palm branches. Sometimes described as an incense burner (thymaterion), it is probably Herod’s own elaborate helmet, adorned with an ivy wreath and dangling cheek-pieces. The reverse shows a tripod, surrounded by the Greek inscription, BAΣIΛEΩΣ HPΩΔOY, meaning “of King Herod”.

4 Prutah

The 4 prutot coin bears an elaborately decorated “Macedonian” shield on the obverse. The reverse is a profile view of the same helmet. Weighing four to six grams, these are rather scarce[4].

2 Prutot

The obverse of Herod’s 2 prutot coin shows an “X” within a circle representing a diadem, the golden headband that symbolized Hellenistic kingship. This may allude to the high priest of the Temple, whose forehead was anointed with holy oil in the form of an X. The reverse shows a three-legged offering table flanked by palm branches[5].

Prutot

There are numerous variants of Herod’s one prutah denomination, which typically weighed between 1.5 and three grams. One type depicts an anchor, badge of the defunct Seleucid Empire, often used on coins of Herod’s Judaean predecessors, the Hasmonean dynasty (140 – 37 BCE). The reverse shows two crossed cornucopiae (“horns of plenty”), conventional symbols of prosperity[6]. Between them is a kerykeion (often described as a “caduceus[7]”), the staff carried by heralds and athletic referees. In 12 BCE, Herod financed the Greek Olympics and actually presided over the games.

Another type bears a palm branch on one side and an aphlaston on the other[8]. The gracefully curved, branching aphlaston or aplustre was a “decorative extension of the stern post of a naval vessel (Melville Jones, 18).” It may represent one of Herod’s proudest achievements: construction of a great artificial harbor at Caesarea Maritima on the coast 55 miles (88 km) northwest of Jerusalem.

Half Prutah

The little half prutah (lepton in Greek) was the smallest Judaean coin.

One type repeats the nautical theme, with a crudely rendered galley on one side, and an anchor on the other[9].

Herod’s most historically interesting coin is the half prutah depicting a seated eagle[10]. About 4 BCE, Herod installed a gilded bronze eagle above the gate of the Jerusalem Temple. This infuriated some religious students, outraged by this seeming violation of the Second Commandment’s prohibition of idols (Exodus, 20:4-6). They tore down the eagle and destroyed it. Herod had them executed. Soon afterward, he died in agony from an uncertain disease.

In the course of his long reign, Herod managed to execute his wife, his mother-in-law, his uncle, and three of his sons. Like so many royal families, it was rather dysfunctional.

In 2007, Israeli archaeologists found Herod’s empty tomb at the Herodium[11], a huge fortified palace he modestly named for himself.

The standard reference for Judaean coins, and an essential book for any serious collector, is David Hendin’s Guide to Biblical Coins (fifth edition, 2010). A few coins of Herod appear in most large coin actions and are widely available from dealers who specialize in Biblical coinage.

* * *

Notes

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samaria_(ancient_city)#Sebaste

[2] Prutot is the Hebrew plural of prutah, a small coin that was the price of a pomegranate.

[3] CNG Electronic Auction 437, February 6, 2019, Lot 190. Realized $525 USD (estimate $200).

[4] CNG Electronic Auction 436, January 23 2019, Lot 242. Realized $900 USD (estimate $150).

[5] CNG Electronic Auction 382, September 7, 2016, Lot 159. Realized $300 USD (estimate $300).

[6] CNG Electronic Auction 393, March 15, 2017, Lot 193. Realized $320 USD.

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caduceus

[8] CNG Electronic Auction 344, February 11, 2015, Lot 162. Realized $150 USD (estimate $100).

[9] CNG Electronic Auction 384, October 12, 2016, Lot 337. Realized $110 USD (estimate $100).

[10] CNG Electronic Auction 333, August 20, 2014, Lot 122. Realized $450 USD (estimate $150).

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herodium

References

Grant. Michael. The Jews in the Roman World. New York (1973)

Hendin, David. Guide to Biblical Coins, 5th edition. New York (2010)

Holum, Kenneth, et. al. King Herod’s Dream: Caesarea on the Sea. (1988)

Jacobson, David and Nikos Kokkinos. Judaea and Rome in Coins: 65 BCE – 135 CE. London (2012)

Lorber, Catharine. “The Iconographic Program of the Year 3 Coinage of Herod the Great”, American Journal of Numismatics 25. (2013)

Melville Jones, John. A Dictionary of Ancient Greek Coins. London (1986)

Meshorer, Ya’akov. Jewish Coins of the Second Temple Period. Tel Aviv (1967)