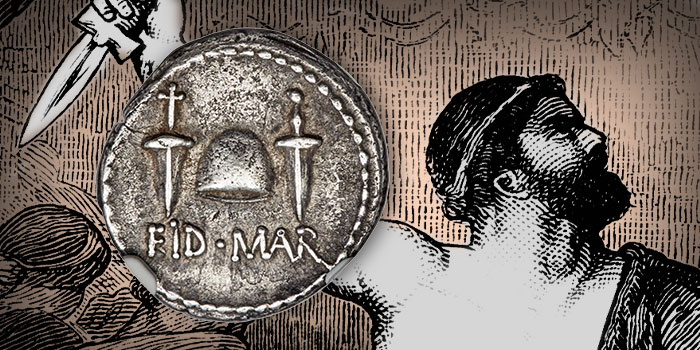

The EID MAR denarius, undoubtedly the most historically important of all ancient coins, is the only Roman coin to mention a specific date, the only Roman coin to openly celebrate an act of murder, and one of the very few specific coins mentioned by a classical author. In his account of the Roman civil wars of 49-31 BCE, the Roman historian Dio Cassius writes:

“Brutus stamped upon the coins which were being minted his own likeness and a cap and two daggers, indicating by this and by the inscription that he and Cassius had liberated the fatherland.”

The EID MAR type is justifiably famous and was selected in a 2008 vote by top numismatists as Number 1 of the 100 Greatest Ancient Coins. Numerous books, articles, and TV productions have illustrated this type, including the most widely used handbook of Roman coins, David R. Sear’s Roman Coins and Their Values Vol. I (no. 1439).

Heritage Auctions is presenting an example of this coin in the upcoming ANA World’s Fair of Money Signature Auction of World and Ancient Coins, scheduled for August 19-20.

The event celebrated by this coin is the assassination of Julius Caesar on the Ides of March (March 15), 44 BCE. The man depicted on the obverse, Marcus Junius Brutus, was one of the ringleaders of the assassination plot, despite being the son of Caesar’s longtime mistress, Servilia. In the centuries since, he has been both hailed as a champion of liberty and damned as the vilest of traitors.

Brutus was born in about 85 BCE, the product of two of Rome’s most distinguished families, the Junii, represented by his father M. Junius Brutus the elder, and the Servili, exemplified by his mother Servilia. The themes of Republican liberty and the defeat of tyrants ran strong in Brutus’ bloodlines. One of his distant ancestors, L. Junius Brutus, expelled the last king of Rome and went on to become the Republic’s first chief magistrate, or Consul. Another ancestor, Servius Ahala, murdered the tyrant Spurius Maelius, who had threatened to overthrow the Republic and install himself as king. Brutus’ father had resisted the tyranny of the dictator Sulla and was murdered on the orders of Sulla’s henchman Pompey the Great during the bloody proscriptions of 78-77 BCE.

After entering public life in 58 BCE, Brutus became a protégé of the conservative firebrand Cato the Younger and later married his daughter, Porcia. Although viewed by many as a paragon of Roman virtues, Brutus was anything but kindly to non-Romans. As a finance officer (Quaestor) in the provinces, Brutus made his fortune by loaning money at the extortionate interest rate of 48 percent to provincial cities, then using Roman armies to squeeze his debtors dry. When Julius Caesar crossed the Rubicon River and plunged the Republic into civil war on 10 January 49 BCE, Brutus was faced with a dilemma: Should he support his friend (and his mother’s paramour) Caesar, or back the Republican cause embodied by his benefactor Cato but led by his father’s murderer Pompey? Despite his hatred for Pompey, Brutus chose to side with him and the Republicans, joining them in exile in Greece in mid-49 BCE.

After Pompey’s defeat at Pharsalus the following year, Brutus sought and obtained Caesar’s pardon. During the dictatorship, he stood in high favor and won many plum positions in the regime, prompting rumors that Brutus was actually Caesar’s illegitimate son. As Caesar grew ever more megalomaniacal, Brutus began to have misgivings about the fate of his beloved Republic. When his friend C. Cassius Longinus asked him to join a conspiracy against the great dictator, Brutus eagerly accepted and became one of its ringleaders.

On the Ides of March, 44 BCE, a cabal of senators led by Brutus and Cassius surrounded Caesar during a monumental session of the Senate, where Caesar was about to announce his plans for the invasion of Parthia. In a bloody, frenzied scene reenacted countless times since, they stabbed him to death. Caesar’s poignant last words were delivered in Greek as Brutus delivered the fatal thrust: “Kai su, teknon?” (“You too, my child?”). Shakespeare would later translate this to Latin to create the immortal line, “Et tu, Brute?”

The conspirators expected to be hailed as liberators, but the Roman populace was horrified by Caesar’s murder and wanted the assassins punished. Brutus left Rome in April barely ahead of a lynch mob. He joined Cassius in assembling a pro-Republican power base in Macedonia, where they could wage war against Caesar’s successors, Marc Antony and Octavian. A successful campaign against the Bessi in Thrace won him acclamation as Imperator, after which he began to strike coins to pay his growing army.

His early coinage follows traditional themes, but his final type, the EID MAR issue of mid-42 BCE, breaks the old Republican taboo by placing his own portrait on the obverse, coupled with the pileus or cap of liberty (traditionally given to slaves who had received their freedom) between the daggers that executed Caesar. The irony is palpable: One of the acts that got Caesar killed was putting his own portrait on coins, prompting fears that he aimed to make himself King of Rome. Now Brutus was following suit while celebrating his betrayal of Caesar on the iconic reverse. The choice of types could be seen as a final, brazen act of defiance as the armies of the warring factions closed for an ultimate clash in northern Greece.

In a final twist of fate, Brutus used the same dagger he had plunged into Caesar to take his own life following the final defeat of the assassins at the second Battle of Philippi on 23 October 42 BCE. The relative rarity of Eid Mar denarii today is doubtless because the type was deliberately recalled and melted down by the victors, Marc Antony and Octavian.