By Steve Benner for CoinWeek …..

By the middle of the third century CE, the Roman Empire was in bad shape.

In 253, when Valerian became emperor, the Empire had had 10 rulers since the death of Severus Alexander in 235. Most of these men had killed the preceding emperor and then taken over; several were generals who had won a battle or two against the barbarians and decided that they themselves would make better emperors.

In addition, there were constant incursions across the borders into Roman territory by barbarians like the Alemanni, Goths, Marcomanni, and the Juthungi, and by the Sassanid Persians. Two large sections of the Empire broke away as independent entities: the Gallo-Roman, centered on Gaul, and the Palmyrene Empire, centered on Syria. The loss of wide swaths of the Empire destroyed much of the tax base, and larger armies required more money, so runaway inflation was also a threat to effective governance.

So Valerian had his hands full when he became emperor, and, along with his son Gallienus, he had to work hard to recover the Empire. Things got worse when Valerian was captured by the Sassanid king Shapur I in 260 and died in captivity. Gallienus had some success in restoring the Empire, but his generals didn’t think he was up to the task and subsequently murdered him in 268. Three of the emperors that followed Gallienus were outstanding generals and are referred to as the Illyrian Emperors: Claudius Gothicus (268-270), Aurelian (270-275), and Probus (276-282). They managed to reconquer the breakaway Gallo-Roman and Palmyrene Empires and drive back the invaders, and by the time of Probus’ death, the Empire had recovered much of its strength.

It was at this point that Carus became emperor.

The History

Very little is known of Marcus Aurelius Numerius Carus’ early life. Most scholars believe he was born in Narbo, Gaul, around 224. He was educated in Rome, and as a Senator he served in various civilian and military capacities before becoming praetorian perfect under Probus in 282. In 283, Probus was killed by mutinous troops at the Pannonian city of Sirmium (which happened to be his birthplace). Carus was proclaimed Roman emperor by the army and sent an announcement to the Senate stating so. He didn’t travel to Rome and paid no heed to the will of the Senate.

Carus had two sons: Marcus Aurelius Carinus and Marcus Aurelius Numerianus. He raised both of them to the rank of Caesar but in early 283, he raised Carinus to the rank of Augustus and put him in charge of the Western part of the Empire. Carus took Numerian with him back to the east to confront the barbarians and the Sassanids. While in the Balkans, Carus campaigned against the Quadi and the Sarmatians on the Danube where he reportedly killed 16,000 Quadi and captured 20,000. For this he was awarded the title Germanicus Maximus.

Before his death, Probus had been planning a campaign against the Sassanid king Bahram II, and Carus decided to go ahead with the war. In 283 CE, Carus invaded Mesopotamia, defeated a Persian army, and captured both Seleucia and Ctesiphon, the Persian capital. Mesopotamia was once again a province of the Roman Empire, and Carus took the title of Persicus Maximus. However, Carus soon died under mysterious circumstances. After a stormy night in either July or August, he was found dead in his tent, possibly killed by lightning. It’s more likely that he had been killed by Arrius Aper, the praetorian prefect and father-in-law of Numerian, or by Diocletian, the commander of the imperial bodyguard.

Now serving as Augustus, Numerian was not as warlike as his father and withdrew from Mesopotamia, returning it to Persian control. The emperor’s entourage moved back across the Tigris and headed toward Rome. He was said to have an eye infection that had him riding in a closed coach. When the coach reached Bithynia or Thrace, a rotting smell was coming from inside, so when it was opened, the dead body of Numerian was found. Diocletian accused Aper of the murder and killed him, whereupon Diocletian was declared emperor.

Carinus headed east to confront Diocletian, and the two armies met at the Margus River in Moesia. Either Carinus won the battle but was killed by one of his tribunes or Diocletian completely defeated Carinus’ army. Whichever version is true, Diocletian was the last man standing and thus became emperor.

Carus

There were several mints in operation at this time: Antioch, Cyzicus, Lugdunum, Rome, Siscia, Ticinum, and Tripolis. The mint at Serdica was closed by Probus. Carus reduced the wight of the gold aureus to 4.6 grams but raised it back to 5.4 before the end of his reign. All the mints issued gold aurei and antoniniani, except Tripolis, which only issued antoniniani. This may explain why there seems to be a lot of gold coins from an emperor whose reign lasted less than a year.

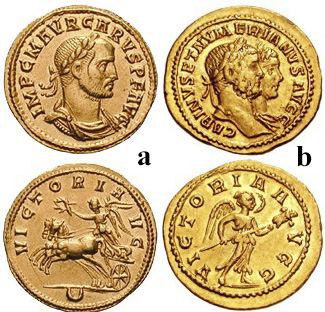

Figure 2a shows an attractive aureus of Carus, and Figure 2b shows an aureus of his sons, Carinus and Numerian, that was minted after Carus’ death.

g., RIC V pt 2. (Triton V. Lot 1025, $5800, 1/16/02). b) CARINUS and NUMERIAN. 283-284

AD, Lugdunum (Lyon) mint. Struck 284 AD. Jugate busts of Carinus and Numerian right /

Victory advancing right, 4.91 g., RIC V 332 (denarius). (Triton V. Lot: 1035, $9,000, 1/12/04).

The antoniniani varied in quality from mint to mint but some could be quite appealing. The two examples in Figure 3 show this variety. Figure 3a shows a well-silvered coin of Carus indicating that the reforms that Aurelian had implemented were still in practice. Figure 3b is interesting because it shows Carus wearing a military helmet. This obverse had been used to a limited extent under Claudius Gothicus and Aurelian but then became more popular under Probus.

emission, October 282 CE. Bust / Pax standing facing. head left, 3.65 g., RIC V 13. b)

CARUS. 282-283 AD. Antoninianus. Lugdunum mint. Radiate, helmeted and

cuirassed bust right / Pax standing left, 4.34 g, RIC V pt. 2, 13. (Triton V. Lot: 2126,

$140, 1/16/02).

The Rome mint produced a number of other denominations. These included the denarius, the quinarius, and the bronze as. Figure 4 shows all three of these denominations. Figure 4a shows an attractive denarius very similar to those produced by the previous emperors, as is the quinarius in Figure 4b. Both these denominations are scare and can be costly to buy in good shape. The bronze coin in Figure 3c has been referred to as a semis and reduced-sestertius, but most numismatists call it an as. There are only three types of these listed in the RIC, and they are very rare.

standing left, 2.6 g., RIC 53. (Numismatica Ars Classica 100, Lot 595, $2000, May

2017). b) CARUS. 282-283 CE. Quinarius. Rome mint. Bust right / Virtus standing left, 15mm,

2.34 g., RIC V 58. (CNG 90, Lot: 1696, $1000, 5/23/12). c) CARUS. 282-283 AD. As. Rome

mint. 1st emission, October 282 AD. Bust right / Carus standing left, 4.52 g., RIC V 61 (Rome;

semis). (Triton X. Lot: 1585, $2200, 1/9/06).

There is one additional bronze coin that was minted only at the Siscia mint and it is shown in Figure 5. It has the bust of Sol facing the bust of Carus on the obverse, and the reverse has Felicitas facing left. This coin was originally minted by Aurelian, who made Sol his personal god and introduced the cult of Sol Invictus to Rome. The cult became very popular, so Carus utilized this in his reign to associate himself with Aurelian. There has been some question as to this coin’s denomination. Even though the coin is not double the weight of an antoninianus, the double radiant crown on the obverse may have meant that it was worth two antoniniani in the marketplace, hence “double” antoninianus.

DEO ET DOMINO CARO INVIC AVG, bust of Sol. radiate and draped. vis à vis bust of Carus,

radiate and cuirassed / FELICITA-S REPVBLICAE. Felicitas standing left. leaning on column.

holding caduceus and transverse sceptre: •XII•, 4.56 g., RIC V 99. (CNG 67, Lot 1750,

9/22/2004)

There were also a number of coins minted by Carus that include both Carus and his son Carinus on one side or the other. The coins included aurei, antoniniani, gold quinarii, and denarii and tend to be relatively rare.

Numerian

Numerian was given the title of Caesar in late 282 by his father and retained this title until early 283 when he became Augustus. Only aurei and antoniniani were minted while he was Caesar; the former are hard to find, but the latter can be purchased at reasonable prices. Figure 6a shows an antoninianus when Numerian was Caesar, and Figure 6b is one when he was Augustus.

282. Radiate, draped, and cuirassed bust right M AVR NUMERIANVS NOB C / Mars advancing

right, holding spear and trophy, 3.55g., RIC V 353. (CNG 476, Lot 542, $100, 9/9/20). b)

NUMERIAN. 283-284 AD. Antoninianus. Lugdunum mint. IMP NVMERIANS AVG, radiate

and cuirassed bust left, holding sear and shield / Pax standing left, holding olive branch and

sceptre: B in left field, 3.34 g., RIC V pt. 2. 395. (GNC 51, Lot 69, $90, 10/23/02).

Once Numerian was Augustus, his mints began to produced denarii, quinarii, and asses, in addition to the aurei and antoniniani. I could not find examples of asses, so they must be extremely rare. The other three are shown in Figure 7. Figure 7a is an aureus with Victoria on the reverse; Figure 7b is a denarius with Pax reverse, and Figure 7c is a quinarius with Mercury on the reverse. None of these three coins are common and can be hard to find. Only the antoniniani, both Caesar and Augustus, can be purchased at reasonable prices.

NUMERIANVS AVG/ VICTORIA AVGG, Victory standing right, 4.22 g., RIC V -. (Triton VII,

Lot 1029, $24,000, 1/12/04). b) NUMERIAN. 283-284 CE. A Denarius. Rome mint. Laureate

and cuirassed bust right / Pax advancing left, holding olive-branch and sceptre, 2.73g., RIC V

430. (CNG 72, Lot 1733, $600, 6/14/06). c) NUMERIAN. 283-284 CE. Quinarius, Laureate bust

right / Mercury standing facing, head left, holding caduceus and purse, 1.89 g., RIC V 437 var.

(CNG 462, Lot 521, $1200, 2/26/20).

Carinus

The coinage of Carinus is similar to that of his brother in that Carinus was Caesar for less than half a year before becoming Augustus and produced coins with both titles on them. But unlike Numerian, Carinus’ mints issued a denarius, a quinarius, a double antoninianus, and an as, as well as an aureus and antoninianus. The double antoninianus and as are very rare, and I could not find any examples of them – though I’m sure the as is similar to that shown in Figure 4c. Figure 8 shows an aureus for Carinus as Caesar on the left and an aureus as Augustus on the right.

282 CE. M AVR CARINV-S NOB CAES. laureate and cuirassed bust right / VICTORIA AVG

wingless Victory standing left on globe, holding wreath and trophy, 4 37 g., RIC V 190. (CNG

108. Lot 664, $21,000, 1/13/04). And CARINUS. 283-285 CE. AV Aureus, Rome mint. 5th

emission, series b-c, early-mid 284 CE. Laureate, draped, and cuirassed bust right / Hercules

standing right, leaning on lion skin-covered club set on rock, 6.24 g., RIC V 235D. (CNG 85, Lot:

1154, $4700, 9/15/10).)

When Carinus became Augustus, mints continued to produce the same denominations, except that the double antoninianus was dropped and the gold quinarius was added. Like the double antoninianus and as, I could not find any examples of the gold quinarius. Figure 9 shows three of the Augustan denominations. Figure 9a is an antoninianus with Victoria on the reverse; Figure 9b is a denarius with a quadriga (a four-horse chariot) on the reverse; and Figure 9c is a quinarius with Virtus standing on the reverse. The denarius and quinarius can be hard to find and expensive, but the antoninianus is readily available on the market and can be purchased in excellent condition at reasonable prices.

draped, and cuirassed bust night / Victory advancing left, 3.77 g., RIC V 220. (CNG 837711). b)

CARINUS. Billon denarius, 283-285 CE. Rome mint. IMP CARINVS PF AVG, laureate,

cuirassed bust right with slight drapery on left shoulder. /P M TR I P COS PP, Carinus, holding

olive branch, driving slow quadriga right, 2.76 g., RIC V-2 226 var (listed only as aureus).

(Numismatica Ars Classica 84, Lot 1153, Mav 2015). c) CARINUS. 283-285 CE. Quinarius.

Ticinum mint. 1st emission, October 282. Laureate and cuirassed bust right / Virtus standing left,

holding spear and resting hand on grounded shield, 2.06 g., RC V 283. (CNG 60, Lot 464, $300,

7/20/22).

In addition to the aforementioned coins, Carinus issued a lot of coins that had both himself and his father and/or his brother on them. He also issued divus (posthumous) coins for his father, brother, and for whom was probably his own infant child, Nigrinian. One of these last coins is shown in Figure 10a: the coin is a divus antoninianus of Nigrinian with the standard eagle and CONSECRATIO legend on the reverse. Carinus also struck coins of his wife. Figure 10b is an aureus of Carinus’ wife Magnia Urbica with Venus on the reverse.

5th emission of Carinus, November 284 CE. DIVO NIGRINIANO, radiate head front / eagle

standing facing, head left, with wings spread, KAA, 3.63 g. RIG V 4/ 4. (Triton XX. Lot: 841,

$1300, 1/9/17).). b) MAGNTA URBICA, wife of Carinus. Augusta, 283-284 AD. AV Aureus.

Lugdunum (Lyon) mint. Struck July 284 AD. MAGNIA VR-BICA AVG. diademed daraped bust

right / VENVS GE-N-ETRIX. Venus standing left, holding apple and sceptre. 4.20 g., RIC 330.

(Triton VII, Lot: 1036, $11,000, 1/12/04).

Comments

Aside from the antoniniani, the coins of this Roman Imperial dynasty are very pricey and hard to find. The gold coins, of course, and are going to fetch the highest prices, but some of the other coins, like the bronze quinarius and denarius, can command a heavy price even if the coin is not particularly attractive (I have several of these: expensive and ugly). The as and double antoninianus must have been very limited issues since it’s hard to find photos of them, let alone one for sale.

* * *

Reference

Hornblower, Simon. The Oxford Classical Dictionary (Antony Spawforth, ed.). Oxford (1996)

Madden, F., C.R. Smith, and S.W. Stevenson. A Dictionary of Roman coins. London (1889)

Sear, David. Roman Coins and Their Values III. Spink (2005)

Vagi, David. Coinage and History of the Roman Empire (2 volumes). Coin World (1999)

Webb, Percy. The Roman Imperial Coinage, Vol V, Part II. Spink and Son: London (1933)

* * *

About the Author

Steve M. Benner has a Ph.D. in engineering from the Ohio State University and worked for NASA at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, for almost three decades before retiring in 2016. He has been an ancient coin collector since the early 1970s and is a member of the ANS, the ANA, and the ACCG. He specializes in coins of the ancient Greek leagues and in Roman Imperial bronzes. Dr. Benner has published over 30 ancient coin articles in various publications and is the author of Achaian League Coinage of the 3rd through 1st Centuries B.C.E. (2008) and History and Coinage of the Ancient Greek Leagues, 5th through 1st Centuries B.C.E. (2018).