By Mike Garofalo for PCGS ……

Thursday, October 5, 1967, was a really terrific day for this author. I was 14 years old, a freshman in high school, and my beloved Boston Red Sox had just played Game 2 of baseball’s 1967 World Series. The Sox pitching ace, Jim Lonborg, shut out the St. Louis Cardinals 5-0, and my boyhood hero, Carl Yastrzemski, hit two home runs to win the game and tie the Series at one game each.

The next morning, I went looking for the story in The Boston Globe about the Red Sox win. The Sox heroics were certainly there, but there was also another story that caught my eye. I had been collecting coins for several years already, and my brother was attending coin shows as a dealer, so this article really piqued my interest.

About 1,500 miles south of me in Miami, Florida, five young men had driven to the affluent neighborhood of Coconut Grove to rob someone. The area was filled with mansions, estates, and palatial summer homes. Inside these mansions must be millionaires, and millionaires must have cash! No one seems to know why the crooks stopped at one particular, massive 42-room mansion when so many other similar estates were nearby. The grandiose home was situated at 3500 St. Gaudens Road, an address well suited for those with an affinity for numismatics but one that likely held no meaning for these robbers.

The five young men were armed and looking for cash and jewelry, but they had no idea that they were about to acquire the rare coin collection of a lifetime. They also didn’t realize how much trouble these coins would cause them. Just before midnight, they stopped the car, donned their ski masks, and proceeded to break into this particular residence.

However, this was no ordinary mansion. It was the home of Mr. and Mrs. Willis H. du Pont, former head of General Motors and E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, the chemical giant. Willis was the youngest of 10 children and had left the family’s homeland of Delaware for the relaxing sunshine of Florida. He had married a Spanish model, Miren de Amezola de Balboa, and they had two children: Victor, age four at the time of the robbery, and his baby brother Lammot, then just one.

Many of du Pont’s neighbors had private security guards watching over them and their property. Willis du Pont felt that the technology of the day would better serve to protect his family. His home was protected by a state-of-the-art alarm system and a network of closed-circuit cameras. Never fully comfortable with being in the public eye due to his wealth and fame, du Pont at least felt protected here.

Shortly after midnight, Willis and Miren were awakened by the sound of their bedroom door exploding open. The lights went on and in came five masked strangers with their guns drawn. One of the robbers yelled, “We want your money. Tell us where it is!” As scary as that must have been, at least they were looking only for money – not to hurt or kidnap the family. Money was something Willis could easily surrender.

The gang had rounded up young Victor from his room, as well as the maid and butler, who were still on duty, and brought them all into Willis and Miren’s bedroom (they left the baby asleep in his crib). Two robbers stayed in the bedroom, forcing Miren to open the small bedroom safe. At one point, Miren panicked and couldn’t remember the combination, only to have a gun shoved in her face. Meanwhile, Willis was escorted downstairs.

In the bedroom safe was some $50,000 in cash and family jewelry, which would not have been a terrible haul on its own. But downstairs was a game-changer! Willis was forced to show them the walk-in safe next to his study. While the robbers were looking for more cash, inside the walk-in safe was one of the most impressive and valuable private coin collections in the country. The robbers realized that this was the haul of their dreams.

The robbers secured six suitcases from the du Pont attic and filled them with books and boxes full of rare coins, gold and silver pieces, and more than 1,000 silver dollars. After packing all of their loot, the family, the maid, and the butler were tied up using a number of Willis’s silk ties. The stolen car that had brought them to the du Pont home was abandoned, and they used Miren’s brand new red Cadillac convertible to make their getaway.

Less than 30 minutes after they left, the butler had freed himself and immediately called police. While waiting for their arrival he untied the rest of the family who all gathered together downstairs. When the detectives arrived and began their investigation, they were perplexed at how these young robbers successfully avoided the sophisticated alarm system. Willis provided the unexpected answer. “The alarm system, unfortunately, had never been turned on.” As for getting into the house, an unlocked patio door meant that they didn’t even need to actually break in.

The Haul

Stolen were approximately 7,000 coins in total. Some 250 Russian Ruble coins from the famed Mikhailovich collection were taken, along with more than 1,000 United States silver dollars.

But all of that paled against the value in the handful of great American rare coins that Willis owned.

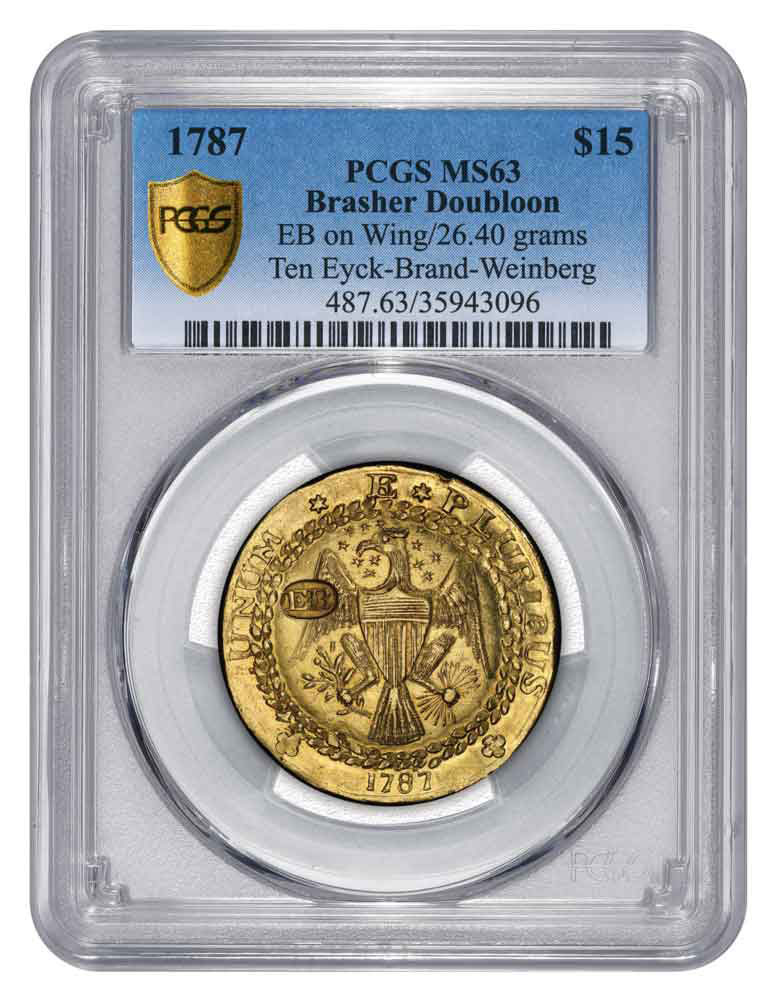

His rarities were legendary in that he owned the collection of 13 private and territorial United States gold coins that were some of the finest known; two specimens of the legendary 1804 Draped Bust Dollar; and the famous trio of coins including the 1866 No Motto Seated Liberty Quarter, Half Dollar, and Dollar – all thought to be unique. Another major rarity stolen was the finest-known 1787 Brasher Doubloon.

Also stolen was more than $4,000 in cash and nearly $50,000 in family jewelry. This was an amazing haul for the inexperienced group of hoodlums. The estimated value of all items stolen easily exceeds $10 million today.

While the local and state police ran the investigation, du Pont hired his own investigators headed by Harold Gray, a du Pont family attorney who traveled the globe trying to recover many of the coins that were stolen that evening. Gray was on the case until 2011, when he passed on at age 85, but not without having had some successful recoveries of a number of important coins.

Aftermath for the Victims

The du Ponts made significant changes to their lives after the robbery. The Coconut Grove mansion was sold within a few months and the family moved to an estate in Palm Beach that was much more secure, boasting not only a security system but also a cadre of armed guards protecting the property 24/7.

Miren’s Cadillac convertible was recovered the next day, but she refused to even get in the car. Within 48 hours Miren had a new convertible to drive. The vast majority of common coins were not recovered and, presumably, sold back into the numismatic marketplace.

We will, however, focus on the items immediately recovered and then the five great rarities that were recovered after the crime and the role that various coin dealers played in their identification and subsequent recoveries.

A Quick Recovery

Although it is believed that much of the jewelry was melted (and the precious stones extracted) so specific jewelry pieces could not be identified, the common coins were likely sold quickly for pennies on the dollar.

In February of 1968, a brief four months after the robbery, the very first coins recovered were 13 Pioneer and Territorial Gold coins ransomed back to du Pont for $50,000. Edward Stanton, a Philadelphia bail bondsman, and his wife, Barbara, handled the transaction in a meeting with two “shady characters” in Philadelphia. Harold Gray had approved the ransom price of $50,000. The coins were returned as the $50,000 in small, unmarked bills were delivered to the crooks, stored in Barbara’s handbag. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was involved in this sting operation, and as soon as the bag changed hands the agents swooped in and arrested the two men. The family had hoped to ransom back all of the coins.

Most of the gold and platinum Russian Rubles of the Mikhailovich collection were recovered when it was being sold for its bullion value. Some 24 years later in 1993, Harold Gray flew to Zurich, Switzerland because two likely du Pont coins were being offered for sale by an Israeli collector – an 1804 Draped Bust Dollar (the Cohen specimen) and the unique 1850 $5 Norris, Gregg & Norris Stockton specimen Territorial Gold coin. In Zurich, Swiss Police, Interpol, and Gray arranged to meet the unnamed collector and purchase the coins. But the couriers of the coins became uneasy and tried to flee Switzerland. They were caught and subsequently released, but the coins were returned to Willis du Pont.

The Brasher Doubloon

The recovery of the 1787 Brasher Doubloon was quite by coincidence.

One of the participants in the robbery of the du Pont home wanted a coin for himself, over and above what the rest of his gang would split up. He conveniently palmed du Pont’s 1787 Brasher Doubloon.

The enterprising hoodlum who stole this coin taped it to his ankle to keep it safe and secure at all times. Eight months after the robbery (in May of 1968), this coin was still taped to his ankle.

Unfortunately for him, he had a difficult temper to control. His wife suffered a beating at the hands of this crook.

But even more unfortunate for this robber was having married the daughter of a prominent Mafia chief. When the father-in-law saw the injury that his son-in-law inflicted upon his daughter, Dad sought to exact revenge. He had his son-in-law beaten within an inch of his life. While at the hospital, the tape was discovered and removed, and the golden prize inside was found. The coin was identified as a stolen du Pont coin and Gray was called in to recover the piece for the du Pont family.

Gray was quoted as saying, “We might never have recovered this coin if the guy had been a better fighter.”

The Linderman Specimen of the 1804 Silver Dollar

Fast forward to 1980, some 13 years after the du Pont robbery.

Tom DeLorey was working for a coin authentication team under the direction and ownership of the American Numismatic Association (ANA). DeLorey received a call from a man in Las Vegas who said that he had an opportunity to buy an 1804 Draped Bust Dollar. He hinted that the coin might very well be the stolen du Pont specimen and insisted that any possible 1804 Draped Bust Dollar had to be authenticated first. But the seller refused to come to the ANA’s headquarters in Colorado Springs.

So, DeLorey agreed to meet the buyer and seller in Las Vegas. But the seller did not show up, and DeLorey assumed that was the end of the discussion.

But just a year later, DeLorey crossed paths again with this stolen coin. A seller had made an agreement with a dealer in Texas to sell him this coin. The dealer demanded that the coin be authenticated by the ANA in Colorado Springs before making any payment. The seller would bring the coin to the ANA and leave it with them to authenticate. If they said it was genuine, the seller would leave the coin, fly back to Texas, and get paid. The ANA’s authentication team sent the authenticated coin to the Texas dealer.

The ANA authenticator handed the coin to DeLorey and asked him what he thought of it. DeLorey went to the library and there he matched the coin to the picture of the Linderman specimen, shown in references and in auction catalogs. The diagnostics all matched. It was the stolen du Pont coin.

ANA Executive Vice President Ed Rochette, and DeLorey convinced the seller to leave the coin overnight while they authenticated it. He agreed, filled out the forms, and paid an authentication fee. As soon as he left, they called officials with the FBI, who came and took custody of the coin. The next morning the FBI came back with mug shots of the man who had submitted the coin as well as those of an older man. The older man was identified as an important member of a Las Vegas crime syndicate.

When the seller came back for his coin, the FBI officers were waiting and arrested him and an older gentleman who was waiting in their car with the motor running. When the case went to court in Denver, both were able to escape conviction, as the jury believed the man’s story about his deceased grandfather giving him the coin and they also felt there wasn’t enough evidence to convict the older man.

Willis du Pont was so grateful that he donated the Linderman specimen to the Smithsonian and the Cohen coin was granted to the ANA Money Museum.

No Motto Quarter and Half Dollar

By September 1999, the trio of 1866 No Motto Seated Liberty coins had been missing for 32 years.

Kevin Lipton, a well-known Beverly Hills coin dealer, was contacted by Steve Teitelbaum, the owner of Los Angeles Coin, about a possible discovery coin that he had purchased over the counter in a collection. Teitelbaum drove to Kevin Lipton’s office and showed him the coin. Lipton immediately confirmed to Teitelbaum that the coin was not a new discovery piece but that it was the missing du Pont No Motto Seated Liberty Quarter.

Teitelbaum contacted the du Pont family and the coin was reunited with them. But that was not the last of the “No Motto” coins to be recovered in such a manner.

A few weeks later, another remarkable occurrence also involved coin dealer Lipton.

Superior Galleries had gone into bankruptcy several years earlier, but Lipton purchased the Beverly Hills building in which they were located. The successor company still occupied the building and as Kevin walked through the coin gallery, he saw a piece that looked interesting in one of their showcases. He examined it closely and when he turned the coin over was amazed to see that it lacked the normal “IN GOD WE TRUST” motto on the reverse.

Lipton immediately knew that this coin was the unrecovered du Pont 1866 No Motto Seated Liberty Half Dollar specimen. He notified the manager of the coin department, Steve Deeds, to the fact that one of the stolen du Pont rarities was sitting in his showcase where anyone could purchase it. It had been sold over the counter for well less than the coin was worth and had sat in their inventory since its purchase a few weeks earlier. They returned the coin to the du Pont family.

The 1866 Liberty Seated No Motto Dollar

Nearly 37 years after the du Pont robbery, one additional rarity was located in February 2004.

But the story begins the previous autumn when John Kraljevich, Jr. received a call from a gentleman who was curious about a coin that American Numismatic Rarities (ANR) had auctioned in September 2003. The coin was an 1866 No Motto Seated Liberty Dollar, one of only two known to exist. The only other specimen of this rarity was the du Pont coin stolen back in 1967. The gentleman inquired how certain they were that only two examples were known and whether there were photographs of the du Pont specimen.

Upon further inquiry, Kraljevich learned that the person had acquired the coin as collateral on loan to a friend. The caller was hoping that the coin in his possession was a third yet-undiscovered example of this rarity rather than the stolen specimen, which he knew he would have to return. Over the next few months, the conversations were irregular yet they continued. When the gentleman, a librarian and book collector from neighboring Maine, photographed the coin and sent the photos to ANR, it matched perfectly. Kraljevich and John Pack, also of ANR, who helped Kraljevich identify the coin with certainty, knew that they had located the long-lost du Pont rarity.

Convinced that this was the stolen du Pont specimen, the gentleman gave the coin to Kraljevich and Pack, and they notified officials at the ANA who, in turn, notified Willis du Pont. At the 2004 Baltimore Coin and Currency convention, all three of the No Motto coins were once again reunited, as they had been back in 1967.

Conclusion

Many of the du Pont rarities were returned, and a grateful Willis du Pont donated them to the ANA Money Museum and to the Smithsonian’s National Numismatic Collection.

He was asked, years later, if he still collected coins. He responded that he did not. But if that response was untrue, du Pont – now in his mid-80s – has kept an extraordinarily low profile in the hobby. His one regret was that his 1879 $4 Stella had never been recovered. But he and his family recovered from the ordeal they had suffered in 1967.

* * *

* * *

Great story, Mike!