By Peter Anthony – Numismatic Guaranty Corporation …….

“We are going to a Lu Xun restaurant,” my friend announced as we left the subway station.

“A Lu Xun restaurant? What’s that?”

“They serve food that appears in Lu Xun stories. It is called Kong Yiji. There are four of them in Beijing.”

I knew that Lu Xun was a famous writer, but a restaurant inspired by him? China is full of surprises.

Lu Xun is the pen name for Zhou Shuren. In his lifetime (1881–1936) he was everything from geologist to medical student to writer to artist to teacher. Today, he is mostly lionized for his stories. Every middle schooler in China reads these. He is considered the father of modern Chinese writing, the first to sweep aside outdated poetical fluff and replace it with common, everyday language.

As a young man, Lu Xun recognized that China needed more than just a political revolution. Stale thinking shackled the country as much as the Qing Dynasty did. In 1902, he turned his back on his own family’s customs. He traveled to Japan on a Chinese government scholarship to study scientific, not traditional, methods of medicine. Among Asian countries, Japan was the quickest to adopt western technology. Many Chinese wanted to follow its lead.

You never know how things will turn out, though. From 1904-05, while Lu Xun studied, Japan and Russia fought a war over which empire would rule northern China and Korea. Japan won. After a 1906 biology lecture, one of Lu Xun’s professors proudly gave the class a bonus, a slideshow of war photos.

One image captured the moment Japanese soldiers chopped off the head of a Chinese spy. In a classroom filled with students from China, this passed without comment. In fact, the audience seemed to approve.

Lu Xun wrote, “Every face was utterly, stupidly blank…if (a country’s) people were intellectually feeble, they would never become anything other than cannon fodder… The first task was to change their spirit, and I decided that literature and the arts were the best means to this end.”

So Lu Xun quit both medical school and Japan. Next stop: Beijing.

Today, although a nearby freeway slices through the city, Lu Xun would recognize his street in Beijing. The store names are different, but the buildings are more or less unchanged. His own apartment at 19 Gongmenkouertiao (try saying that a few times fast) Road remains. It does have a new neighbor: a museum, the Lu Xun Museum.

For ten years, Lu Xun holed up at number 19 while he wrote and struggled to stay afloat. There were papers on geology and translations into Chinese of foreign authors like Victor Hugo. At last, after the Xinhai Revolution in 1911 swept aside the Qing Dynasty, China was ready to face itself. It was Lu Xun’s hour. He was at the center of a literary revolution with his fierce satires like The Diary of a Madman and The True Story of Ah Q.

One of his most popular works is Kong Yiji, the story that lent its name to the restaurant. This tale follows the memories of a young busboy at a tavern in Luzhen, an imaginary town. One of the tavern’s regulars is Kong Yiji, a ne’er-do-well who failed the xiucai, or imperial examinations.

In that era, working-class men wore short coats, while their “betters” dressed in long gowns. Inside the tavern, it was easy to spot who was who — the long-gowns sat, the short-coats stood. Except for Kong Yiji. Dressed up like a scholar, he was still only welcome to stand at the bar. There he drinks, endures jibes and passes out one marinated aniseed bean apiece to passing children.

Without a real occupation, Kong Yiji steals to get drink money. When he gets caught, he is beaten. That is how his legs get broken. The busboy ends with, “After this, we were again bereft of Kong Yiji for an extended period of time.”

“‘Kong Yiji still owes me those nineteen coppers!’ the manager said, as the year neared its end, taking the slate down again. ‘Kong Yiji still owes me nineteen coppers!’ he repeated at the Dragon Boat Festival, in early summer the following year. At the Mid-Autumn Festival he said no more about it; nor at the end of the year. “I never saw him again—I suppose Kong Yiji really must have died.”

There were actual deaths to reckon with, too. On March 18, 1926, soldiers of the warlord government fired on a peaceful protest, killing 200 students. Lu Xun called it “the blackest day since the founding of the Republic.” The warlord Zhang Zuolin reportedly ordered his arrest after this. Whatever his reason, Lu Xun definitely left Beijing and kept on working.

His output was prodigious. Besides fiction, there were essays and opinion piece after opinion piece—enough to fill ten volumes between 1932 and 1936. Somehow he found time to be prominent in The Freedom League, a civil rights organization, and also lead the League of Left-Wing Writers. As a teacher, he spurred many writers and artists on to greater heights.

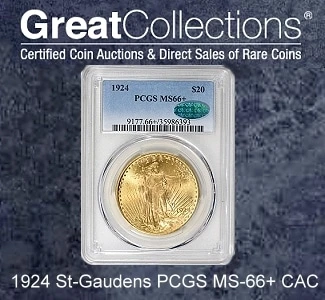

Strolling through the museum exhibits between families and classes of schoolchildren, one display catches my eye. It is a group of old coins. Yup, Lu Xun was a numismatist, too. He contributed to a coin design that exists as a pattern struck by the Tianjin Mint. He actively collected old coins himself and wrote an essay about their history.

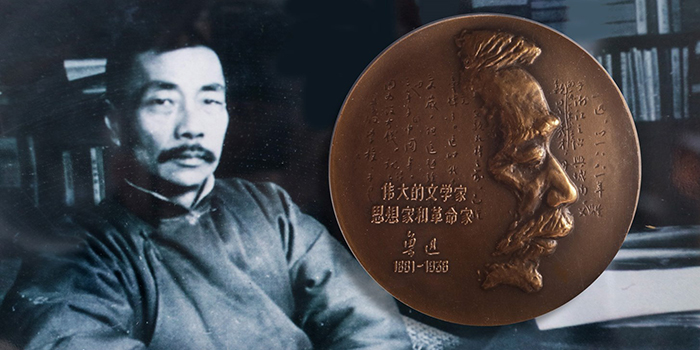

So Lu Xun himself collected coins, but what is there for us to collect of him? Top billing goes to a great work by Chen Jian, the 1982 Panda coin designer. This same artist also created the memorable 1997 Yellow River Culture Shooting the Sun gold coins’ design (Nick Brown’s favorite). On the 1988 copper Lu Xun medal, only the edge of the author’s face rises above the fields. The rest of the surface is left blank, veiled in darkness, except for inscribed writing. It’s a bold, unforgettable image. This 60 mm round copper medal shouldn’t cost a lot, and it isn’t considered real scarce (it also exists in silver), yet go try to find it! NGC has graded but one (shown above).

While Chen Jian’s extraordinary portrait stands out, there are several other medals worth hunting for. The artist Feng Yunming, who has been rediscovered and now has a devoted following, designed a 1981 two-piece Lu Xun medal set. I have seen as much as $1,000 asked for a raw set. The China Mint Company struck a different pair in gilt brass and silver (shown above) for Lu Xun’s 100th anniversary in 1981. Still others, with less clear origins, were issued, too.

Lu Xun’s role as an educator makes him a natural subject for school-related medals. An example is a pair of beautiful Shanghai Mint medals from 2014. These were issued in copper and silver for the 8th Anniversary of the Lu Xun Memorial Hall at a Nanjing high school. The copper medal has a low mintage of 200, while the 100-gram silver issue is a mere 36.

When Lu Xun passed away, one newspaper hailed him as “the soul of the nation.” His influence can still be felt all around China, touching even restaurant names. So, is Kong Yiji restaurant as tasty as a Lu Xun story? I recommend both the eating—especially the delicious whole chicken in a clay pot (the marinated aniseed beans are interesting)—and the reading.

Note: Quotations are from The Real Story of Ah Q and Other Tales, translated by Julie Lovell, 2009.

* * *

Peter Anthony is an expert on Chinese modern coins with a particular focus on Panda coins. He is an analyst for the NGC Chinese Modern Coin Price Guide as well as a consultant on Chinese modern coins.