![]()

By Michael T. Shutterly for CoinWeek …..

Part I | Part II

* * *

Iconoclasm (“image smashing”) was very popular within the Byzantine military during the eighth and ninth centuries, but the bulk of the population strongly opposed the Iconoclasts (“image smashers”). The decree of the Second Council of Nicaea in 787, which declared Iconoclasm to be heretical, was well-received throughout most of the Byzantine Empire. Iconoclasm was a lost cause.

Or so it seemed.

The Iconodule (“icon venerating”) Empress Irene (ruled 797-802) reigned extravagantly, spending huge sums on popular domestic projects while neglecting the Empire’s northern frontier with Bulgaria. She was deposed and exiled in 802. She was succeeded by her finance minister, Nikephoros I (ruled 802-811).

Nikephoros seems to have been indifferent to the issue of the veneration of icons, and instead focused his attention on restoring the Empire to solvency and strengthening the frontiers. He won several stunning victories against the Bulgarian Tsar Krum, but he threw everything away by chasing Krum into the mountains where Nikephoros and his army were ambushed and destroyed. Krum celebrated by having a drinking cup made from Nikephoros’ skull.

Nikephoros’ son, Staurakios, was badly wounded in the same battle, although he managed to return to Constantinople. Due to the seriousness of his injury (his spine had been severed), he was forced to abdicate. Staurakios was then succeeded by his brother-in-law, Michael I Rhangabe (ruled 811-813).

Michael I briefly brought stability to the Empire, but he threw everything away by launching another disastrous war against Krum. On July 11, 813, Michael abdicated in favor of Leo the Armenian, a successful general who took the throne as Leo V. The new emperor pledged to support the veneration of icons, going so far as to kneel before an icon of Christ when he entered the imperial palace.

The war against the Bulgarians ended in 814, largely as a result of Krum’s death by natural causes. Now secure on his throne, Leo V showed his true colors on the issue of icons: with peace now restored, Leo renewed the iconoclastic policies of the Isaurian emperors. One of his first actions was to force the Iconodule Patriarch Nikephoros into exile.

Leo had a young son, Symbatios, whom Leo renamed Constantine soon after being crowned. Leo’s choice of a new name for his son was deliberate, echoing as it does the pairing of the iconoclastic Emperors Leo III and Constantine V, and Leo V and Constantine VI. Leo crowned Constantine as his co-emperor at either Christmas of 813 or Easter 814, after which Constantine regularly appeared on Leo’s coins.

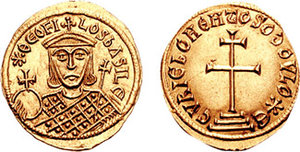

The obverse of this solidus depicts Leo V with the inscription LЄ On ЬASILЄЧ (“Leo the King”). The reverse presents a crowned facing bust of Constantine with the inscription COnSτ Anτ ∂ЄSP Є (“Constantine the Despot”). Despot did not have the pejorative meaning it has today: the word comes from Greek and literally means “Master of the House.” It was just another of the many titles given to the emperors.

This solidus was struck in Constantinople circa 813-820. It is catalogued as Sear 1627 and sold for $6,500 at an auction in January 2012.

Leo V followed the leads of Leo III and Leo IV by including his son Constantine on his silver miliaresion. Fortunately, the miliaresia of Leo V are easy to distinguish from those of his predecessors: Leo V’s miliaresion names him and his son as “Kings of the Romans” rather than just “Kings”, as had been the practice under both Leo III and Leo IV.

This miliaresion was struck in Constantinople circa 813-820. It is catalogued as Sear 1628 and sold for $475 at an auction in August 2013.

According to an old account, in 803, Leo the Armenian and his companions Thomas the Slav and Michael the Amorian encountered a monk who prophesied that Leo and Michael would both become emperors, while Thomas would be acclaimed emperor but would die without being crowned. When Leo became emperor in 813 he gave Michael and Thomas senior military commands.

Leo and Michael later had a falling out when Leo came to suspect, probably with good cause, that Michael was plotting against him. On December 24, 820, Leo sentenced Michael to death, with the execution scheduled to take place after Christmas. Early Christmas morning, Michael’s supporters disguised themselves as choristers and murdered Leo while he was attending Mass in a chapel in the imperial palace. Michael was taken from prison and crowned emperor, his legs still bound with chains as no blacksmith could be found to remove them.

A Kinder, Gentler Iconoclasm

Michael the Amorian became emperor as Michael II (ruled 820-829). He supported the Iconoclastic cause but did not actively persecute the Iconodules. Michael recalled the deposed Patriarch Nikephoros from exile but did not restore him to the Patriarchate.

The first half of Michael’s reign was troubled by a revolt led by his former comrade in arms, Thomas the Slav. It took nearly three years to put down the revolt, which severely weakened the Byzantine military. The Arabs took advantage of the Empire’s weakness, conquering Crete in 824, and launching an invasion of Sicily in 827.

Michael’s first coins portray him on both obverse and reverse. The obverse of this solidus portrays Michael wearing a garment known as a chlamys, with an inscription reading * mIX AHL ЬASILЄ (“Michael the King”). On the reverse, he wears a loros, and the inscription reads mIXAH-L ЬASILЄЧ’ Є (“Michael the King”). The chlamys was a long purple cloak that represented the Emperor’s political authority, while the loros was a long garment symbolic of the burial sheet of Jesus and represented the emperor’s religious authority.

This coin, once part of the Hunt Collection, was struck in Constantinople in 820/1-822. It is catalogued as Sear 1639 and sold for $18,000 against a $20,000 estimate at an auction in May 2016.

Michael crowned his eight-year-old son Theophilos as co-emperor in Spring 821. Theophilos soon began appearing on the coins with his father. Michael appears on the obverse of this solidus, wearing a chlamys, with an inscription reading *mIX AHL ЬASILЄЧS (“Michael the King”). Theophilos appears on the reverse, wearing the loros, with an inscription reading ΘЄOFI LO ∂ЄSPS +Є (“Theophilos the Despot Faithful”).

This coin was struck in Constantinople circa 821-829. It is catalogued as Sear 1640 and sold for $3,500 at an auction in May 2018.

Michael’s miliaresion was struck in Constantinople sometime between 821 and 829, (probably) to memorialize Theophilos’ coronation as co-emperor. It follows the pattern set by Leo V, with the coin identifying Michael and Theophilos as +MIXA HLS ΘЄOFI LЄЄC ΘЄЧ BASILIS RO MAIOҺ (“Michael and Theophilos Kings of the Romans”). This coin is catalogued as Sear 1641 and sold for $320 at an auction in September 2010.

The Last Iconoclast

Michael II died of natural causes on October 2, 829. He was the first emperor to die peacefully and in possession of the throne since Leo IV, 49 years earlier. His son Theophilos took possession of the throne without opposition.

Theophilos (ruled 829-842) was much more fervent in his support of Iconoclasm than his father had been; he was also much less successful as a military commander than his father had been. Where Michael II had been a poorly educated soldier who became a great general, Theophilos was a well-educated, highly cultured man who never won a war. Theophilos greatly admired Islamic art and culture but had the misfortune to spend most of his reign fighting – usually unsuccessfully – against the Arabs. His family’s hometown, Amorium, became the largest city of Asia Minor during the reign of Michael II, but that only made it a primary target for the Arabs, who captured and leveled the city in 838; Theophilos literally could not go home again.

Theophilos was noted in his own time as a fair and just ruler. One of his first acts as emperor after his father died was to execute the men who had assassinated Leo V – even though that assassination saved Theophilos’ father from execution and gave him the imperial throne. Theophilos’ took the position that the murder of an anointed emperor – particularly when that murder took place before the altar during a religious service – was a sacrilege that could not be tolerated.

Theophilos’ first coins portray and name him alone as emperor. The obverse presents a facing bust of Theophilos with an inscription reading *ΘЄOFI LOS bASILE (“Theophilos the King”). The reverse design consists of a Patriarchal Cross on three steps with the inscription CVRIE bOHQH TO SO dOVLO*E (“May the Lord Help Your Servant”). Somewhat oddly, the words of the inscription are all in Greek but use Latin lettering.

This coin was struck in Constantinople circa 829-830 and is catalogued as Sear 1655. It sold for $4,000 at an auction in January 2005.

There is a tradition that Theophilos’ oldest son, Constantine, was born in the late 820s. But records from the period indicate that Theophilos only met and married Constantine’s mother, Theodora, in 830. Constantine does not appear on Theophilos’ coins until about 833, and he is missing from the coins (other than those commemorating him as a deceased emperor) after about 835. All of this suggests that Constantine was born about 831-833 and died about 835.

The solidus shown above would have been struck in Constantinople while Constantine was alive, that is, sometime between 831 to 835. The obverse presents a facing bust of Theophilos with the inscription * ӨЄOFI-LOS ЬASILЄ (“Theophilos the King”), while the reverse portrays Constantine with the inscription + COҺSτAҺτ ∂ЄSPOτI X (“Constantine the Despot”).

This solidus type is catalogued as Sear 1654; it is very rare and does not often appear in the market. The coin shown here sold for $11,000 against a $6,000 estimate at an auction in May 2016. Similar specimens have sold in recent years for prices ranging from $7,500 to $22,000.

As his imperial predecessors had done, Theophilos struck a miliaresion that (presumably) commemorated the coronation of Constantine as co-emperor. The six-line reverse inscription reads + ΘЄOFI LOS S COҺST AҺTIҺOS δЧ LЧ XPISTЧS PISTЧ ЬASIL ROMAIO (“Theophilos and Constantine Servants of Christ and Faithful in Him King of the Romans”).

This miliaresion was struck in Constantinople circa 830-83 and is catalogued as Sear 1660. It is somewhat scarce, appearing very infrequently in the market. But when it does, it doesn’t usually bring a huge price tag; the specimen shown here sold for £460 (about $611.18 at the time) at an auction in February 2019.

Theophilos had a second son, Michael III, who was born in January 840. Later that same year Theophilos crowned the infant Michael as his co-emperor and struck miliaresia to commemorate the event. The five-line reverse inscription on this coin reads + ӨЄO FILOSSMI XAHLЄCӨЄ bASILISRO MAIOҺ (“Theophilos and Michael by the Grace of God Kings of the Romans”). The coin was struck in Constantinople circa 840-842 and is catalogued as Sear 1664. It sold for $625 against a $300 estimate in January 2005.

Theophilos issued five different types of miliaresia, three of which were very different from the miliaresia of his predecessors in that they name Theophilos alone. None of the earlier emperors ever struck a miliaresion solely in his own name – each of them seems to have issued his miliaresion at the time of the coronation of his son as co-emperor, and each named himself and his son on the coin. Theophilos’ “sole rule” miliaresia were presumably struck before Constantine was born (that is, before circa 830-833), or after Constantine died but before Michael was born (that is, from circa 835 to 840).

The miliaresion shown here is one of those that only names Theophilos. Based upon its general “type”, it was probably minted during the period between Constantine’s death and Michael’s birth. The reverse inscription reads . +ΘЄOFI LOS δЧLOS XRISτЧS PIS τOS ЄҺ AVτO BASILЄЧ RO MAIOҺ (“Theophilos Servant of Christ and Faithful Believer, Sole King of the Romans”). The coin was minted in Constantinople circa 830/831-838 and is catalogued as Sear 1661. It sold for $850 at an auction in September 2010.

Sometime between the death of Constantine and the birth of Michael III, Theophilos struck a gold solidus that harkened back to the coins of the Isaurians, who portrayed deceased members of their dynasty on their coins. The solidus shown here portrays Theophilos on the obverse and his deceased father, Michael II, and his deceased son, Constantine, on the reverse. The obverse inscription reads * ΘЄOFI LOS bASILЄ Θ (“Theophilos the King”) while the reverse reads simply + MIXAHL S COnSτAnτINs (“Michael and Constantine”).

This solidus was minted in Constantinople. Most references indicate that it was struck circa 831-842, but insofar as Constantine was probably alive until 835, it was probably minted circa 835-842. The coin is catalogued as Sear 1653 and sold for $1,100 at an auction in May 2012.

At some time in the late 830s, the mint in Constantinople struck a solidus honoring Theophilos, his wife Theodora, and three of his daughters. The obverse portrays the crowned facing busts of Theophilos, Theodora, and their oldest daughter, Thekla; Theophilos wears a chlamys, while each empress wears a loros. The obverse inscription reads ΘЄK ΘЄOF ΘЄ (abbreviated versions of “Thekla Theophilos Theodora”). The reverse portrays crowned facing busts of his daughters Anna and Anastasia, with an inscription reading AnnASAnASτASIA (“Anna and Anastasia”).

The coin neither names nor portrays Theophilos’ oldest son, Constantine, nor Theophilos’ two youngest daughters, Pulcheria and Maria. This suggests that it was minted in the very narrow window of time between the death of Constantine (circa 835), and the births of Pulcheria and Maria (circa 836 and circa 838, respectively). It appears to be a ceremonial issue, and it very likely commemorated Thekla’s coronation as an empress, which occurred after Constantine died.

Thekla’s younger brother, Michael III, succeeded their father as emperor in 842, but the reverse of the first solidus struck during Michael’s reign names and portrays Michael and Thekla together – and her portrait is larger than his. The obverse portrays Theodora, who served as regent for the two-year-old Michael and was apparently Empress Regnant in the early part of his reign.

The coin is extremely rare, and there are no commercially available images of it. The Dumbarton Oaks Catalogue notes the existence of just three specimens, all in museum collections.

Late in his reign Theophilos struck a gold solidus with Michael III. The obverse depicts Theophilus with a short beard, wearing a chlamys, and holding a Patriarchal Cross and an akakia (this was a bag of purple silk that contained dust and symbolized human mortality). The inscription reads + ΘЄOFI LOSbASILЄs Θ (“Theophilos the King 9”). The reverse portrays the beardless Michael III facing, wearing a loros, and holding a globus cruciger and cruciform scepter. The inscription reads • + MIXAHLuЄSPOTIS A (“Michael the Despot 1”).

In earlier times, coins struck in the imperial mint in Constantinople often identified by number the workshop in which they were struck. This practice was long obsolete by the time this solidus was struck, but the mint continued to place random workshop numbers on the coins – such as the Θ (“9”) at the end of the obverse inscription on this coin and the A (“1”) at the end of the reverse inscription – apparently out of force of habit.

Some have argued that this coin was struck during the reign of Michael III (reigned 842-867), and that it follows the pattern begun by the iconoclastic emperors of depicting their deceased predecessors on their coins. This seems very unlikely. First, Theophilos is depicted wearing a chlamys, while Michael is wearing a loros, and at this time it was customary for the loros to be worn by the junior emperor (if the coin portrayed two living emperors) or by a deceased emperor (if the coin portrays living and deceased emperors). Second, Theophilos is given the title Basileus (“King”) while Michael is called “Despot”, and typically when one Emperor is identified as “King” and the other as “Despot”, the title of “King” goes to the more senior of the two. Third, when the Iconoclasts portrayed deceased members of their dynasty on coins, it was customary to portray all of their deceased predecessors, and this coin does not include Michael II, the deceased grandfather of Michael III.

This extremely rare coin is catalogued as Sear 1657. It was probably issued for ceremonial purposes at the time of Michael’s coronation as Theophilos’ co-emperor. Despite having been mishandled (it was one time mounted in jewelry); it still brought a price of $3,250 at an auction in January 2009.

The solidus that Theophilos struck in Sicily is the most affordable solidus from his reign, and one of the most common and affordable of all Byzantine gold coins. Sicily was under heavy attack by the Arabs throughout Theophilos’ reign, and the mint struck huge quantities of gold coins to pay the soldiers who were defending the island. It has generally been assumed that the coins were struck in Syracuse, but some inconsistencies in the coins suggest the possibility that the coins may also have been at several mints besides Syracuse.

The Sicilian coins were struck on small, thick planchets. The quality of the gold during Theophilos’ reign was generally very good, but the weight of the coins tends to be about 12% less than that of the coins of Constantinople. During the reign of Michael III, the gold quality would deteriorate drastically, and the coins eventually contained much more copper than gold.

The coin has a very basic design, naming and portraying Theophilos on both sides. He wears a loros and holds a Patriarchal Cross on one side and wears a chlamys and holds a globus cruciger on the other. One common variety of this coin, not shown here, adds an abbreviated version of his title as bASIL (“King”) to the inscription.

Another very rare variety (also not shown here) names and portrays Theophilos’ deceased father, Michael II, and his deceased son, Constantine, on the reverse.

The solidus shown here sold for $600 against a $500 estimate in May 2002.

The End of Iconoclasm (For Real This Time)

Theophilos’ health was never good; he died of dysentery on January 20, 842, not quite 30 years old. As was the case when Leo IV died in 780, a sickly iconoclastic emperor died young, leaving the throne to a very young son under the regency of a vigorous dowager empress who happened to be an Iconodule.

In March 843, Empress Theodora formally restored the veneration of icons. She also ordered that the body of the Iconodule Empress Irene (ruled 797-802) be placed in the lavish tomb of the Iconoclastic Emperor Constantine V, with Constantine’s remains to be burned and the ashes dispersed to the winds. For her actions on behalf of Orthodoxy, Theodora is venerated as a saint in the Orthodox Church. Iconoclasm would never again rule the Empire.

Collecting the Coins of the Iconoclasts

Sear (1987) is an excellent reference catalog for the general collector, providing good descriptions of about 50 different coins of the second period of the Iconoclastic Controversy. For more advanced numismatists, Volume Three, Part I of the Dumbarton Oaks Catalogue offers more detailed descriptions of the coins, accompanied by outstanding plates, with additional significant background information. Grierson (1982) provides a thorough overview of the coinage.

* * *

References

Grierson, P. Catalogue of the Byzantine Coins in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection and in the Whittemore Collection, Vol. Three, Part 1: Leo III to Michael III 717-867. Dumbarton Oaks: Washington, D.C. (1973)

–. Byzantine Coins. Methuen & Co.: London. (1982)

Ostrogorsky, G. History of the Byzantine State (Hussey, J. translator). Rutgers University Press: New Brunswick, NJ. (1969)

Sear, D.R. Byzantine Coins and Their Values (2nd Edition). London. (1987)

Theophanes. Chronicle (Turtledove, H., editor and translator). University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia. (1982)

* * *

About the Author

Michael T. Shutterly is a recovering lawyer who survived six years as a trial lawyer and 30 years working in the financial services industry. He is now an amateur historian who specializes in the study of ancient Rome and the Middle Ages, with a special interest in the art and history of the coins of those periods. He has published over 50 articles on ancient and medieval coins in various publications and has received numerous awards for his articles and presentations on different aspects of the history of the ancient and Medieval world. He is a member of the ANA, the ANS, the Association of Dedicated Byzantine Collectors, and numerous other regional, state, and specialty coin clubs.