By Peter van Alfen for American Numismatic Society (ANS) ……

As long as there have been shipwrecks, there have been attempts to salvage the cargo – especially when that cargo consisted of gold coins and other precious metals. Here, Dr. van Alfen writes about specific shipwrecks and the medals that commemorated their recovery efforts.

* * *

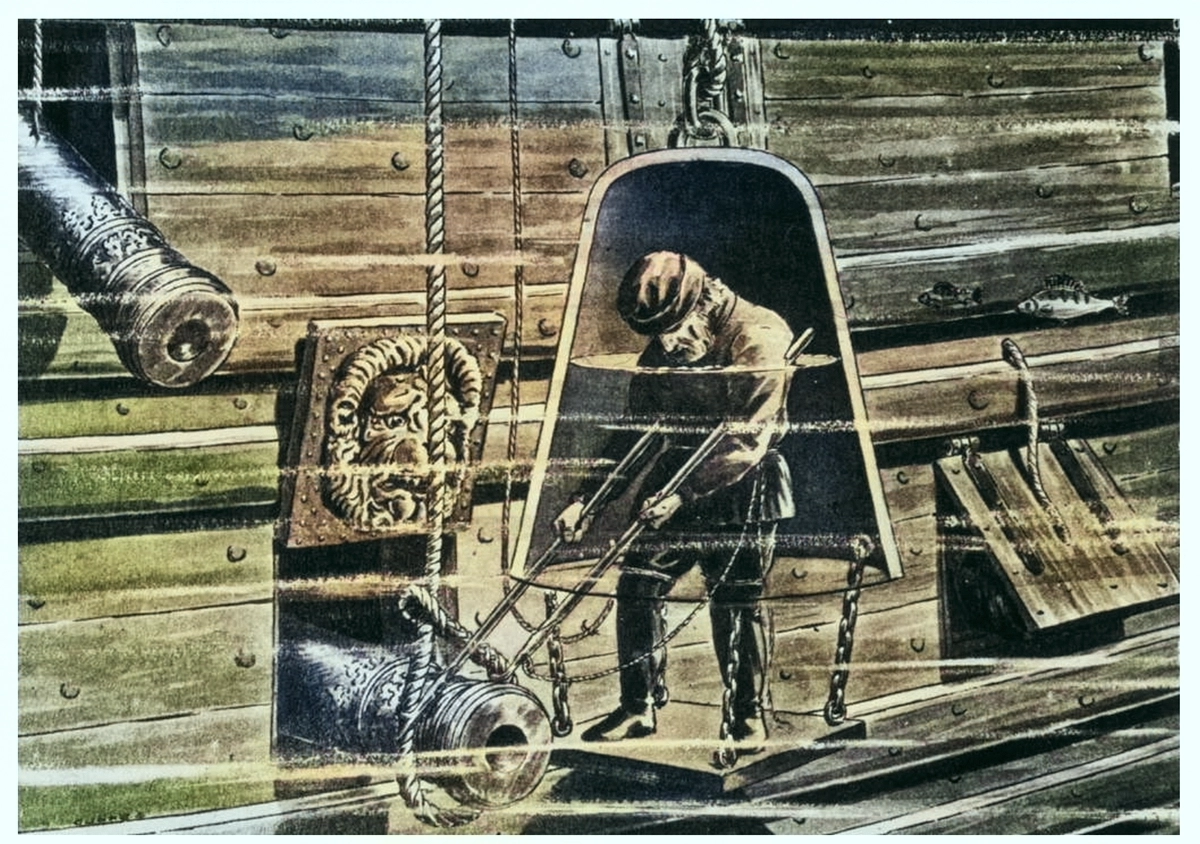

Since antiquity, wrecked ships lying in shallower and accessible waters were often salvaged, but within the limitation of divers being able to hold their breaths and the lifting capabilities available to them. Along with the rapid advances in ship technologies, the 17th century also saw advances in salvage technologies, including the perfection of diving bells and heavy lift mechanisms.

In a recent dissertation, Michael Jung offers an extensive overview of early modern salvage technologies along with the culture of science and treasure hunting that evolved along with it, including an account of Hans Albrecht von Treileben, a German-Swedish military engineer.[1] Along with others, Treileben developed a working combination of diving bell and heavy lift pinchers that were demonstrated on recovering cannon from various Baltic shipwrecks, including the ill-fated Swedish warship Vasa, which sank in 30m of water in Stockholm harbor on its maiden voyage in 1628. Amazingly, the largely intact hull of the ship was raised in 1961 and now resides in a museum in Stockholm. Given the enormous expense and value of shipboard artillery, especially bronze cannon, all efforts were made to recover sunken guns when possible. Treileben’s successful demonstration recovering cannon from Vasa in 1658 earned him and his consortium a salvage monopoly from the Swedish king, which greatly increased their reputation.

Treileben was subsequently contracted to recover valuables from the wreck of a Dutch ship, Wapen van de Prins, that sank in a storm near the city of Westkapelle on the island of Walcheren in the province of Zeeland in October 1659 on a return voyage from Cadiz. In a fascinating study, Albert Meijer and Jan de la Hayze detail the life of the captain of the ship, Jan Vinkaert, also known by his nickname “Waterdrincker,” the history of his ship and its last tragic voyage.[2] Having served for years as a captain for the Zeeland Admiralty, and gaining fame commanding a fireship during the Battle of Scheveningen in August 1653 (Fig. 4), Vinkaert was furloughed in 1657 and subsequently purchased the retired fleet vessel Vlissingen from the Admiralty, which he renamed Wapen van de Prins, to try to make a living in regional trade. As part of a convoy of ships returning from Cadiz with tons of silver aboard, much of it meant to be steered towards the Zeeland Mint to produce Dutch trade coinage, Vinkaert decided, when close to home, to peel off from the rest of the convoy and head for his home port of Veere. He never made it. A sudden gale caught him off-guard and drove his ship onto a sandbank near Westkapelle where it was battered to pieces, costing Vinkaert his life along with that of most of his passengers.

Among those who had consignments of silver aboard the ship was the prominent Walcheren trader Marcelis van der Goes, who organized Treileben’s expedition to Zeeland, which in the end recovered most of the lost silver from the wreck, some of which was turned over to the Zeeland Mint for striking coins (Fig. 5), and some of which, presumably, was also used in 1660 to strike a commemorative medal at the behest of Goes (Fig. 6).[3]

The obverse depicts Treileben’s salvage operation, while the reverse has a lengthy Latin inscription that translated reads: “To commemorate the salvage, by a wonderful device exceeding the arts of previous centuries, near Walcheren and in a rough sea, under the auspices of delegates of the States of Zeeland and the care of Marcel Goes, of a great amount of minted and unminted silver, gemstones and artillery from a sunken and broken ship deep beneath the sea, with the objects returned to owners according to the law” (trans. Saunders and Vanhoudt). The artist is unknown but could very well be Matthys Hooft de Jonge, a silversmith and engraver who became master of the Middelburg silversmiths’ guild in 1660, and who succeeded his father as engraver of the Zeeland Mint. He also produced a medal for the Zeeland Admiralty that stylistically is reminiscent of the medal for Goes.[4]

Shipwreck Medals of George Bowers

In any event, this was not the only medal struck to commemorate recovered shipwrecked silver in the 17th century.

During the brief reign of the English King James II (r. 1685–1688), Massachusetts treasure hunter William Phips located the wreck of the 600-ton Spanish galleon Nuestra Señora de la Limpia y Pure Concepción, which sank in a storm off the island of Hispañola on September 28, 1641. Phips journeyed to England to find backers for his recovery operation, initially receiving support from King Charles II, but ultimately it was the Duke of Albemarle who financed the salvage expedition. Phips managed to recover over 34 tons of gold and silver from the wreck in 1687, apparently without the need for specialized equipment like Treileben’s. With so much of the loot flowing back to England, James II subsequently knighted Phips, and two medals by the artist George Bower were struck to commemorate the recovery, both of which are discussed in detail in Christopher McDowell’s new Betts Medal Companion (Figs. 7–8).[5]

![Figure 7: Silver medal by George Bowers issued in 1687 commemorating the salvage of the shipwreck of the Nuestra Señora de la Limpia y Pure Concepción, which is taking place in the foreground of the reverse side of the medal. The Latin inscription Naufraga Reperta can be translated “shipwrecked [goods] recovered.” (ANS 0000.999.34762).](https://coinweek.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/1687_Nuestra_Senora_de_la_Limpia.webp)

Centuries later, in 1978, treasure hunters from Seaquest International Inc. relocated the remains of the wreck and found an additional 60,000 coins, 10 of which were donated to the ANS in 1987 (Fig. 9) by the notorious Juan Suros, who was convicted in 1990 of stealing coins from the Society.[6]

While still Duke of York, James II himself was involved in another shipwreck in 1682, when the frigate he was aboard,HMS Gloucester, struck a sandbank off the Norfolk coast. The Duke was rescued, but around 250 others lost their lives. Shortly thereafter a medal also by George Bower was issued to commemorate the event (Fig. 10). In 2007, the wreck of Gloucester was discovered, initiating the proper archaeological recovery of items, some of which were displayed at an exhibit in 2023 at the Castle Museum in Norwich.

* * *

Sources

[1] M.W. Jung, “Kultur- und Technikgeschichte des Gerätetauchens in der Frühen Neuzeit,“ PhD dissertation (Saarbrücken, 2023), pp. 161–170. See also, J.E. Ratcliffe, “Bells, Barrels and Bullion: Diving and Salvage in the Atlantic World 1500 to 1800,” Nautical Research Journal 56.1 (2011), pp. 34–56; and D. Cressy, Shipwrecks and the Bounty of the Sea (Oxford, 2022), which looks at shipwrecks as social events in 16-18th century England.

[2] A. Meijer and J. de la Hayze, “Een marinekapitein die voor zichzelf begon,” Archief Koninklijk Zeeuwsch Genootschap der Wetenschappen (2015), pp. 5–42.

[3] G. van Loon, Beschryving der Nederlandsche Historipenningen: of beknopt Verhaal van’t gene sedert de overdracht der heerschappye van Keyzer Karel V. op Koning Philips zynen zoon, tot het sluyten van den Uytrechtschen Vreede, in de Zeventien Nederlandsche Gewesten is voorgevallen, vol.II, book 6 (Graavenhaag, 1726), pp. 477-479; J. Saunders and H. Vanhoudt, eds., Gerard van Loon. Medallic History of the Low Countries (1555–1716), vol. II (2021), p. 350, no. 1660-32.

[4] J.W. Fredericks, Dutch Silver: Wrought Plate of the Central, Northern and Southern Provinces from the Renaissance to the End of the Eighteenth Century (The Hague, 1960), p. 8; M.G.A. de Man, “Over het Grootzegel der Admiralteit van Zeeland,” Jaarboek van het Koninlijk Nederlandsch Genootschap voor Munt- en Penningkunde 9 (1922), pp. 78–84. L. Forrer, Biographical Dictionary of Medallists (1907), vol. III, p. 461, attributes this medal to Johannes Loof.

[5] C.R. McDowell, The Early Betts Medal Companion. Medals of America’s Discovery and Colonization (1492–1737) (New York, 2022), nos. 66 and 67.

[6] See D. Yoon, “Theft by Abstraction”, ANS Magazine 2017, vol. 1, pp. 37–44.

* * *

* * *