By Michael Beall for CoinWeek …..

Portraits of important persons in ancient times are among the most sought-after pieces of ancient coinage, though key biblical characters are seldom depicted on contemporary coins. Jewish law during the Second Temple period, including the second commandment, forbade the depiction of human beings in any form, and Christian iconography on coins does not surface until the early fourth century. Representations of Christ are not widely seen until the end of the seventh century CE.

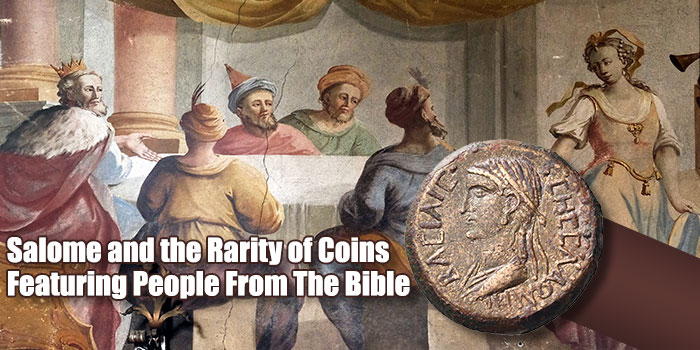

The Armenian king Aristobulus IV (a great-grandson of Herod the Great) struck one of the most fascinating portrait coins from Biblical times in 66/67 CE.

His portrait appears on the obverse while his wife, the infamous Salome, who danced for the head of John the Baptist some 30 years earlier–as told in Matthew 14:6-11 and Mark 6:14-29–appears on the reverse. This until recently extremely rare bronze coin is a two-for-one in that it features both a portrait of a member of the Herodian dynasty and one of the most storied women in Biblical history.

In this article, we will describe these two people’s role in history and chronicle recent activity in the market for this coin, where we have seen an influx of supply in recent years.

Aristobulus and Salome

The Herodian dynasty was one of the most important series of leaders in Jewish and early Christian history.

Their rise to power begins with Antipas, an Edomite that converted to Judaism. He was a friend of Rome as the emerging empire consolidated its position in the Levant in the middle of the first century BCE. His son Herod I (“the Great”) was appointed king of Judea in 40 BCE by the Triumvirate marshaled by Mark Antony.

Herodians held various positions of power in Israel and surrounding areas until the end of the first century CE. There are at least five Herodian’s mentioned in The Bible although some are bit players. In terms of coinage, some Herodians that ruled areas with negligible Jewish populations took the opportunity to place their portraits on coins. These leaders of various titles include Herod Phillip II (4 BCE to 34 CE), Tigranes V (6-12 CE), Tigranes VI (60-62 CE or later), Herod of Chalcis (41-48 CE), Agrippa I (37 to 44CE), Agrippa II (49/50 to 94/95 CE), and Aristobulus IV (54-72 CE).

Aristobulus IV (aka Aristobulus of Chalcis) was the son of Herod of Chalcis by his first wife Mariamme -a granddaughter of Herod the Great (I). When Herod of Chalcis died, Aristobulus initially was awarded no rank but when Nero became emperor, Aristobulus was appointed ruler of Lesser Armenia –a small territory north and west of Greater Armenia. It is unclear but generally believed Aristobulus retained ruler status until 92 CE although the exact territory changes somewhat. His coinage is struck on an irregular basis with key dates being 66/7CE (2 coins -one with Salome the other with an inscription honoring Nero) and 70/71CE (no Salome but a reverse honoring Titus). The coins struck in 66/67 CE and 70/71 CE appear to show support for Rome during the Jewish War.

Salome was the daughter of Herodias and Herod II (aka Philip II) and she was probably in her mid-teens when she performed an erotic dance for Herod Antipas on his birthday. By that time, Herodias was married to Antipas, having divorced Antipas’ half-brother Phillip – an action that John the Baptist publicly criticized. In exchange for her special dance, Antipas granted Salome a wish. At the urging of her angry mother Herodias, Salome requested that the head of the imprisoned John the Baptist be delivered to her on a platter. Antipas reluctantly agreed, having more of a feeling of curiosity rather than contempt for John the Baptist.

The story of Salome and the beheading of John the Baptist is told in two Gospels although she is not mentioned by name. However, she is named by Josephus in his Jewish Antiquities (Book XVIII, Chapter 5), which confirms we are talking about the correct Salome. Her story is told numerous times in art, film, and on the stage. Her image in the Christian tradition is one of a very young seductress, while a few portray her as an innocent pawn in a foolish promise that led to the death of John the Baptist. John’s head on a platter is also featured on a coin from Malta, minted between 1557-1568 (pictured above).

In any event, owning an ancient coin with a portrait of such a storied person (even if she is then in her late 40s) would qualify as a prized part of any Biblical coin collection. The portrait of a Herodian king is a bonus!

Salome for Sale

As mentioned at the outset, the Aristobulus/Salome coin has been considered as extremely rare with the available specimens so few and in such poor condition that the dating of the coin was in question.

In May of 2013, the first to appear in many years was auctioned in CNG Auction 93 (Lot 93) and hammered at $70,000 USD ($84,000 with buyer’s fees). The coin was described as Very Fine; a generous grade in our opinion, and perhaps “for the type”–numismatic talk for grading on a curve–was implicit. In CNG 96, a specimen described as Good/Fine (Lot 653) was sold a year later for $45,000 hammer ($54,000 with fees). In January 2016, a far superior example, described as a Good/Very Fine, hammered at $160,000 (over $190,000 with fees).

Two coins were sold in 2016, two in 2018, and two more in 2019. So far in 2020, eight examples have been sold, and two were on the auction block in late October. Prices have softened dramatically as one might expect, as the two lower-grade examples above illustrate.

In tandem with the Salome coin, Aristobulus With Inscription coins are also appearing in auctions with greater regularity. Has a hoard been discovered? My sources believe not; it is more likely an area has been located that is currently being combed with metal detectors. However, a large find remains a possibility.

Potential buyers of the Salome coin face a dilemma. Clearly, this rare coin is not as rare as once believed. It is impossible to know how many more will appear and what price levels will ultimately prevail. I would not be afraid to buy since this is unlikely to become a common coin and prices have definitely come down to levels where a much broader group of collectors now have a chance to own this special coin.

* * *

Sources

Hendin, David. Guide to Biblical Coins, Fifth Edition. Amphora: New York. 2010. Print (pp. 273-277).

Kovacs, Frank L. Armenian Coinage of the Classical Period. Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. Lancaster/London. 2016. Print (p. 51).

Meshorer, Ya’akov. “Coins of the Holy Land”, Ancient Coins in North American Collections. American Numismatic Society: New York. 2013. Print (pp. 180-182).

The Complete Works of Josephus. William Whiston, transl. A.M. Kregel Publications: Grand Rapids, Michigan.

* * *

Be sure to check out CoinWeek’s Ancient Coin Expert Mike Markowitz talking with Beall about the author’s stunning personal collection in the video below

* * *