By Tyler Rossi for CoinWeek …..

German World War I medals are viewed today through three main lenses: as simple vehicles for propaganda espousing Teutonic virtues; as permissible artistic expressions of war fatigue; and lastly as early 20th-century “attack ads” against the Entente Powers. Regardless, these views are informed by hindsight. To me, the more interesting question is: How did the world view these pieces contemporaneously?

To answer this question, we must first understand the innate biases inherent in a public document not released by the Central Powers about the Central Powers. Mainly the German soldier’s supposedly innate barbarism and the imposing menace of Prussian militarism. Shaped both by German actions and British reactions, these biases were strengthened by Germany’s defeat in 1918. By the end of the war, the allied nations managed, both purposefully and accidentally, to twist the public perception of these fascinating medals.

George Francis Hill, Keeper of the Department of Coins and Medals at the British Museum, published an “educational” pamphlet in 1917 to assist the British public in identifying and understanding these German war medals. Titled The Commemorative Medal in the Service of Germany, this pamphlet while highly inflammatory is a fascinating insight into the British psyche at the end of the war. This is perhaps to be expected, for the two nations were engaged in a life-and-death struggle.

Hill opens his treatise by describing the production of German medals as “the most curious of the campaigns which have been conducted by Germany”. While I tend to agree with this statement, Hill’s reasoning is quite unforgiving and even slightly vindictive.

In principle, the author agrees with current-day scholarship as to Germany’s intent of “influencing the minds of neutrals and of maintaining enthusiasm for the war within her own borders”. However, he immediately states that Germany did not achieve the desired result and spends the subsequent 23 pages thoroughly ridiculing the messaging and artistic style of said medals.

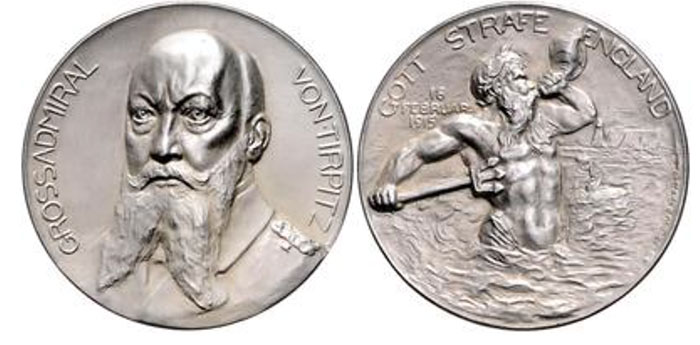

Condemning Germany’s so-called “naturally” occurring tendency for “hero-worship”, Hill belittles the fact that many German medals of the time featured famous royals or significant military leaders – while seemingly ignoring Britain’s near-fetishization of her own war heroes. Hill assumes that the stern, militaristic bearing of these individuals is intended to be an “official expression of frightfulness”, yet they are also described as “wistful,” “genial,” or even “on the verge of tears.” The medals featuring Grand Admiral Von Tirpitz, such as the example below, do indeed show the admiral’s piercing gaze and furrowed brow. Yet, while the emotions are perhaps exaggerated for propagandistic effect, he is far from a pitiable caricature.

With the legend, “Gott strafe England”, which translates as “May God Punish England”, this type was clearly intended to inspire domestic confidence in the strength of German naval arms. It is one of a series of medals hailing the commencement of unrestricted submarine warfare. While the figure of Neptune is not quite as imposing as the artist probably intended, it still is a solid piece of propaganda.

In another dig at the artistic skills of German medallic artists, Hill states that the portrait of Crown Prince Wilhelm on the “Young Siegfried” medal must be a caricature, and if not, “the caricaturist’s occupation is surely gone.” When the Crown Prince’s bust is compared to a later photograph, it shows a relatively high degree of resemblance. He does indeed have a high forehead with a receding hairline as well as a large nose and weak chin. Perhaps Mr. Hill had never seen a photograph of the man. Hill also states, presumably in jest, that it was an “omission” not to bring the artist–the famed German medallist Karl Götz–up on charges of lèse majesté for insulting the monarch.

The reverse, which depicts the crown prince as the naked mythological hero Siegfried is a bit hyperbolic. Especially since Prince Wilhelm was an inexperienced commander, instructed by his father (Kaiser Wilhelm II) to defer to more experienced men, who still lost the 1916 Verdun offensive. Hill notes that the four-headed hydra representing the Entente powers is, despite all Siegfried’s efforts, unscathed.

One medal that I believe Hill is correct about features former German chancellor Otto Von Bismarck in medieval armor standing on water with two eagles at his feet.

The obverse imagery is typical of late 19th- to early 20th-century German Romanticism and the neoclassical artistic movement. On the reverse is the five-line Latin legend “Ceterum censeo Britanniam esse delendam”, which translates to “For the Rest, I Hold That Britain Must Be Destroyed”. It is remarkably like Cato the Elder’s constant refrain of “Ceterum autem censeo Carthaginem esse delendam” (“Furthermore, I consider that Carthage must be destroyed”). The imagery evoked by this medal harkens back to historic Teutonic martial culture and Rome’s dogged rivalry with the North African empire of Carthage.

Nevertheless, it is, as Hill remarks, quite “theatrical,” and it appears as if “the hero [Bismarck] has taken refuge in an arm-chair from the rising tide.” The design does not live up to its historical significance.

Quickly moving on from the serious rah-rah German propaganda medals, Hill dishes out even more scorn for the satirical medals – perhaps the most famous being Karl Götz’s privately issued Lusitania medal.

One of the most famous WWI German medals, this was intended as a satire “mock[ing] the Allied obsession with ‘business’ and derided the supposed impartiality of the USA.” Interestingly, Hill does not dwell on this medal, simply pointing out the controversy surrounding the date on it. Götz mistakenly dated the sinking as May 5, though the British ship RMS Lusitania was sunk by a U-boat on May 7. Hill even calls the “deductions” and assumptions of the British people as to why Götz misdated the medal as “sinister” and states that he “doubted” there was any message hidden in the incorrect date.

Moving on from critiquing a list of medals, Hill next discusses Götz’s artistic style. Breaking Götz’s work into two parts, Hill manages to be simultaneously complementary and insulting. For example, he gives the backhanded compliment of calling Götz a “competent craftsman”. This is, as Hill describes, reminiscent of Renaissance portraiture. One example of this style is a silver medal of German fighter pilot Manfred von Richthofen, otherwise known as “The Red Baron”.

The second type, exemplified by the Lusitania medal, was meant to “amuse the populace.” According to Hill, they are overcrowded and make “no attempt at composition.” Another example of Hill’s second type is titled “American Neutrality.” A caricature of Woodrow Wilson is pictured on the obverse with the president wearing a laurel wreath on his head and a stole decorated with Germany’s imperial eagle and Austria-Hungary’s double-headed eagle. The reverse has Uncle Sam surrounded by weapons of war with a bag of money labeled $100,000. Götz was obviously mocking America’s supposed neutrality and 100% real financial windfall at the expense of the Central Powers.

Perhaps, if Hill and Götz were not on opposing sides of WW1, the British Museum curator might have had kinder words for the German engraver.

It is obvious that the perspectives of the British intellectual class were deeply colored by the war, and it is probably too much to ask of these men to have maintained an impartial façade after watching their countrymen march off to war and die fighting. G. F. Hill’s booklet is only one example of this bias but it is a fascinating window into a lost world.

* * *

Sources

https://digitalcollections.ucalgary.ca/asset-management/2R3BF1FUS9QEY?FR_=1&W=1792&H=1009

https://www.money.org/ana-blog/wwi-remembrance

https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/how-a-german-medallion-became-a-british-propaganda-tool

* * *

About the Author

Tyler Rossi is currently a graduate student at Brandeis University’s Heller School of Social Policy and Management and studies Sustainable International Development and Conflict Resolution. Before graduating from American University in Washington D.C., he worked for Save the Children creating and running international development projects. Recently, Tyler returned to the US from living abroad in the Republic of North Macedonia, where he served as a Peace Corps volunteer for three years. Tyler is an avid numismatist and for over a decade has cultivated a deep interest in pre-modern and ancient coinage from around the world. He is a member of the American Numismatic Association (ANA).