Nickel and US Coinage by Lianna Spurrier for CoinWeek …..

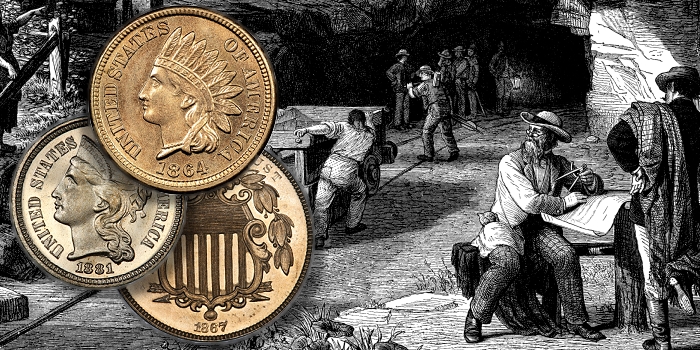

Unlike copper, silver, and gold, nickel is a fairly new addition to coinage around the world. It was used in a few ancient Bactrian issues, but wasn’t seen in coins again until the mid-1800s. It didn’t appear in American coinage until the  Flying Eagle and early Indian Head cents. It disappeared briefly but saw a triumphant return in the nickel three- and five-cent pieces of 1865 and ’66.

Flying Eagle and early Indian Head cents. It disappeared briefly but saw a triumphant return in the nickel three- and five-cent pieces of 1865 and ’66.

Why the sudden adoption of this somewhat obscure metal?

The short answer is fairly simple: Joseph Wharton.

Origins

In recorded history, nickel was first extracted from a German copper mine in the 1600s. In its raw form, it had a light brown-red color, and the workers thought it was a different form of copper ore. When they failed to extract any copper, they blamed Nickel, a mythological demon, and came to call the rock kupfernickel, or “copper demon”.

Years later, in 1751, Swedish alchemist Baron Axel Fredrik Constedt identified properties of the kupfernickel that determined it wasn’t copper at all, but a new element. He dropped the beginning of the name and called his discovery “nickel”.

Nickel is a very hard metal – significantly more so than any of the traditional coinage metals. As such, it was quite difficult to strike and not an ideal candidate for coinage. So how did it get there?

First Small Cents

Nickel deposits weren’t found in America until 1853. The Gap mine of Pennsylvania, which opened as a copper mine in 1849, found large deposits of an ore they called “mundic”. It was cast aside and stored until finally being studied in 1853 when it was discovered that it was primarily nickel. The mine was renamed to the Gap Nickel Mine Company and changed their focus.

In the meantime, the United States Mint was starting to look for an alternative to the cumbersome and expensive large cent. They began experimenting with copper-nickel alloys, ultimately settling on 88% copper and 12% nickel at the suggestion of James Booth, the melter and refiner. With a large nickel supply available in America, this seemed like an excellent solution. The large percentage of copper softened the alloy, making it relatively easy to strike.

The Gap Nickel Mine Company supplied nickel to the US Mint through 1860, when it was shut down and the Mint had to get nickel from other countries. However, the Gap mine wasn’t quite finished yet.

Enter Joseph Wharton

Joesph Wharton was born to a wealthy family in 1826 and became a successful businessman as an adult. He was involved in education, founding the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania, and was also a founder of the Bethlehem Steel  Company and Swarthmore College. In addition, he was invested in mining and manufacturing, having worked with zinc, iron, coal, and copper by his mid-30s. He developed close ties with officials at the Mint, and through them learned of the need for nickel. Seeing an opportunity, he purchased and reopened the Gap mine in 1862, alongside a nickel refinery in Camden, New Jersey.

Company and Swarthmore College. In addition, he was invested in mining and manufacturing, having worked with zinc, iron, coal, and copper by his mid-30s. He developed close ties with officials at the Mint, and through them learned of the need for nickel. Seeing an opportunity, he purchased and reopened the Gap mine in 1862, alongside a nickel refinery in Camden, New Jersey.

He made his first delivery of nickel to the Mint in early 1864, but it seems that his supply wasn’t enough. Shortly thereafter Mint Director James Pollock, wrote, “Our present stock of nickel will be exhausted in a few days and an adequate supply cannot be obtained from any source … We are therefore shut up to the home supply, from the works of Mr. Wharton; but if we could receive all made at his establishment the amount would be wholly insufficient.” Pollock had begun suggesting a bronze cent in 1863, and he continued his efforts.

Wharton was able to use his political influence to delay the passing of legislation to remove nickel from the cent, but he couldn’t stop it, and the composition was changed. Wharton was now left with $200,000 invested in a mine and refinery focused on producing a metal with little use; it was too difficult to work with to be desired in most industry.

Pivoting to Higher Denominations

In a pamphlet issued by Wharton as a last-ditch effort to stop the cent composition change, he made several suggestions. Not only did he call for the cent to be copper-nickel, but also the three-cent piece, the five-cent piece, and the dime.

He expected that his mine would be able to increase production and argued that this token coinage would allow the government to make a large profit. While too late to counteract the cent’s composition change, this wasn’t the end for Wharton.

He expected that his mine would be able to increase production and argued that this token coinage would allow the government to make a large profit. While too late to counteract the cent’s composition change, this wasn’t the end for Wharton.

During the Civil War, a large number of three-cent fractional notes had been issued that the government now wanted to withdraw from circulation. The current three-cent piece, made of billon and containing 90% silver by 1864, was subject to hoarding and melting for its silver content.

How best to get a three-cent piece to circulate? Reduce the precious metal content. Wharton, of course, began lobbying for a copper-nickel composition, which was accepted, giving us the first 25% nickel coin in 1865.

Encouraged by this success, Wharton then focused his efforts on the five-cent piece. Half dimes didn’t circulate well either as they also fell victim to hoarding, and America simply needed more circulating coinage. A bill authorizing a 75% copper and 25% nickel five-cent piece was passed in May of 1866, which ultimately led to the Shield nickel.

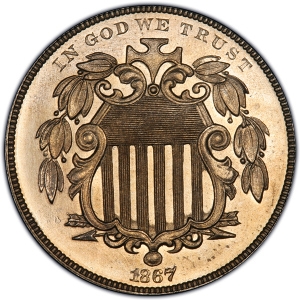

The Shield Nickel

With little time to create an original design, a modification of the shield obverse found on two-cent pieces was adopted with a fairly simple reverse. An obverse featuring Abraham Lincoln was considered but expected Southern backlash discouraged the idea.

The early days of the nickel were not easy. The metal proved very difficult to strike, allowing for only around 15,000 coins to be struck per die. For comparison, the average Indian Head cent die lasted for 200,000 coins. The Mint was frantically creating new dies throughout the beginning of the series, which led to many quality control issues. Die cracks are the standard rather than the exception and finding a specimen without any striking issues is difficult.

The early days of the nickel were not easy. The metal proved very difficult to strike, allowing for only around 15,000 coins to be struck per die. For comparison, the average Indian Head cent die lasted for 200,000 coins. The Mint was frantically creating new dies throughout the beginning of the series, which led to many quality control issues. Die cracks are the standard rather than the exception and finding a specimen without any striking issues is difficult.

To add to the struggle, the public response was less than ideal. The design was highly criticized, the shield mistaken for things like a gridiron or a tombstone. To make matters worse, the stars and stripes on the reverse reminded some of the Confederate flag, which was not well-received in the North.

Most of these complaints came from numismatists, not the general public, but were still an unwelcome reaction. The stripes were ultimately removed from the reverse in 1867 to help with some of the striking problems. Gradually the Mint learned how to work with nickel, and they improved die life as the series progressed. The coins circulated well, and the composition was ultimately a success. In fact, it remains unchanged to this day, making it the only denomination whose composition hasn’t changed in over 150 years, with the exception of war nickels during World War II.

Moving Forward

Wharton continued to supply the Mint with nickel through the Liberty nickel series, though he was not their only supplier. In fact, in 1884, the Mint received 2,000 lbs of nickel from England and Germany that was so hard that it was virtually unusable. The Mint contracted Wharton to convert this into usable blanks.

Wharton’s business expanded beyond coinage, and he became the only supplier of nickel in the US and provided a significant portion of the worldwide supply. When the Gap mine became exhausted in 1893, he was forced to purchase nickel from a mine in Canada to refine. He sold his Camden refinery and the exhausted mine in 1902 to purchase shares in a new company, the International Nickel Company, or INCO. This company still exists today, now known as Vale and headquartered in Canada. The location of the Gap mine, however, is now an Amish community known as Nickel Mines, Pennsylvania.

Without Wharton, there would have been no domestic supply of nickel in the 1860s, making it unlikely that the Mint would have adopted the metal for so much of our coinage. The copper-nickel cents could have been the last noteworthy use of it, and our small coinage could have had a very different history.