An Editorial by Charles Morgan – Editor, CoinWeek.com …..

In July of last year, American publisher Krause Publications released the 10th edition of The Standard Catalog of World Coins: 2001-Date. This book serves as the most comprehensive encyclopedia of all coins struck by or for each country in the world, tracking issues starting with Afghanistan’s decimal coins and ending with the dollar coinage of Zimbabwe.

At 1,344 pages, The Standard Catalog of World Coins: 2001-Date is an impressive volume. But the prodigious output of new coin designs from each of the world’s mints has not only rendered this book obsolete, but rendered the concept of a single-volume encyclopedia devoted to 21st-century world coins untenable.

Consider this.

Since its debut in 2007, The Standard Catalog of World Coins: 2001-Date has increased in size by an average of 118 pages per year. Should the annual output of new coins from the world’s mints continue at this pace, the 94th edition of The Standard Catalog (which, one assumes, would be scheduled for publication in the year 2100) would exceed 11,000 pages. This assumes that coins will continue to be produced and that the medium doesn’t find itself replaced by digital or altogether different forms of payment.

Which means that, by the end of this century, the number of new coin designs issued by the world mints wil dwarf the entirety of all known coinage struck from the middle ages to the year 2000.

But that’s nothing compared to the actual number of pieces struck.

The United States Mint alone has already struck more than 180 billion coins. That number could exceed one trillion circulating coins by the end of the century. Add to that all of the circulating coins that will be struck by every nation across the globe. The number of coins that will be produced this century (ceteris paribus) will be simply staggering.

And believe it or not, despite the fact that almost none of the coin issues will be what one would naturally consider rare, there will still be a built-in collector base for them. Coin collectors of all ages and experience levels have traditionally enjoyed collecting their country’s circulating coinage. For many, discovering and accumulating the older coins that circulate alongside newer ones is the first act of a budding collector.

And believe it or not, despite the fact that almost none of the coin issues will be what one would naturally consider rare, there will still be a built-in collector base for them. Coin collectors of all ages and experience levels have traditionally enjoyed collecting their country’s circulating coinage. For many, discovering and accumulating the older coins that circulate alongside newer ones is the first act of a budding collector.

After doing this a while, it becomes apparent to these collectors that there are gaps in their collection, coins they can’t find. Perhaps they will buy an informative book or magazine, or read about their preferred series online. And in order to acquire these missing coins–the coins they couldn’t find in their change–collectors have trade for them or buy them from other collectors or coin dealers. It is at this point that new coin collectors enter the numismatic marketplace.

But even as global circulating coin production pushes into the trillions, circulating coins aren’t the cause of the explosive growth of Krause’s Standard Catalog and these coins pose little threat to the rare coin industry as it’s currently constituted. Instead, the cause of that irruption belongs to the seemingly endless cavalcade of collector coin issues, the vast majority of them to be struck at mints that operate not as government bureaucracies but as for-profit businesses.

And as these corporate mints have become innovators and leaders in the marketplace, the more traditionally-structured mints have followed suit. The result of this industry transformation has been a dramatic redefinition of what a coin is as a physical object; as a social construct; and what role the coin-producing mints play in the numismatic marketplace.

The Redefinition of “Coin”

What is a coin?

No matter how one answers the question today, that characteristics that make a metal disc a “coin” have changed dramatically over the course of the past hundred years.

Before the Great Depression crippled the global economy in the 1920s and ‘30s, many of the leading industrialized countries adhered to some version of the gold standard. The circulating coins of this period (especially the higher denominations) were, more often than not, struck in either silver or gold.

At the height of the Depression, the production of gold circulating coinage was suspended. In many countries gold coins were either devalued or recalled, leaving silver as the de facto coining precious metal. Then, after World War II, some countries were faced with concerns about the continued circulation of silver coins. The United States, for example, suspended the production of silver coinage 50 years ago.

For the collecting hobby, especially in the U.S., the withdrawal of silver coins from circulation couldn’t have come at a better time.

As silver coins began to rapidly disappear from pocket change, collectors flooded into the marketplace. The value of coins grew dramatically, and the allure of collecting and investing in coins hit the mainstream. A lot of the U.S. industry’s leading dealers launched their careers during this exciting period. Many have related to me over the years that they were able to earn more money selling coins as teenagers than their parents were able to earn working professional jobs.

By the end of the 1960s, silver coins had all but disappeared from circulation in America. I imagine that a similar story played out elsewhere around the world when base-metal discs replaced silver coins.

A hundred years ago, the idea that the coinage of every country in the world would have little to no intrinsic value would have troubled economists and lay people alike; usually, intrinsically valuable coins disappeared from circulation in times of hardship or war. Today it is accepted without much consideration. Most people alive today have never spent a coin with any precious metal content (that doesn’t mean such coins aren’t being made, of course).

The Redefinition of “Coin”, Part II

The social and psychological fallout from the withdrawal of silver and gold from commerce, and the role it has played in the public’s fascination with gold and silver coins, is worth a deeper look.

In the 1930s, the United States experienced a commemorative coin boom. During that decade, the United States Mint produced dozens of silver half dollar coins that were sold to the public at a profit over face value.

The coin market in the U.S. was much smaller then than it is now – and these were tough times, financially – but even though many of these special collector coins brought new collectors into the market, it was only a matter of time before the Mint’s output exceeded the market’s ability to keep pace. The commemorative bubble soon collapsed. Production was suspended for the duration of World War II, but afterwards there was little interest in making this type of coin. Only three were issued between 1946 and 1954, and for the next 20 years the United States Mint neither desired to nor was required to strike commemorative coins for collectors.

But major changes to the global market were afoot, and while the U.S. Mint may have had little interest in producing and promoting coins for collectors, the world mints were developing and growing markets in this material.

One could arguably say that the global collector coin industry that took shape after 1945 marked the end of the era of modern coinage and the beginning of the postmodern period that we find ourselves in today. In the postmodern period, public and private mints have rushed to satisfy growing collector demand by striking coins that were different from “traditional” coins but resembled them in many ways. And while these new collectibles were (legally speaking) coins, they were never meant to circulate and were often struck in denominations unfamiliar to most people. Some were even legal tender in remote locales that had little (if anything) to do with the motif on the coin, or the market in which the coins were sold.

How else would you explain a 2015 issue that bears the effigy of Queen Elizabeth II on one side and an equestrian portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte on the reverse? This coin was struck for Ascension Island, a remote and isolated landmass that has no indigenous population.

How else would you explain a 2015 issue that bears the effigy of Queen Elizabeth II on one side and an equestrian portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte on the reverse? This coin was struck for Ascension Island, a remote and isolated landmass that has no indigenous population.

Much like money with no basis in precious metals, it’s unthinkable that such a coin would have been struck 200 years ago.

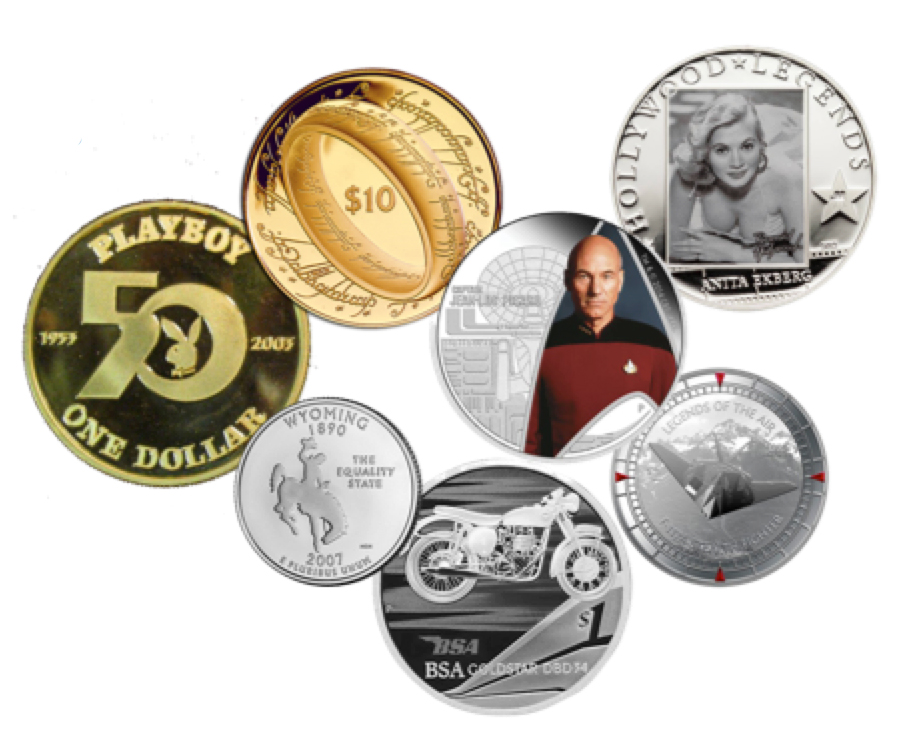

Increasingly, many of today’s collector coins have little to do with the culture of their countries of issue. They have become global, not only in their intended distribution footprint but also in cultural scope. Such coins might tie in with a popular film, a beloved children’s book, a popular comic strip or a comic book superhero.

One can, notionally, conduct a commercial transaction with money backed by the full “faith and credit” of the government but that is otherwise designed to promote the Lord of the Rings films, the 50th Anniversary of Playboy magazine, or iconic cartoon characters like Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny.

Going in a different direction, mints have also sought to differentiate their collector coins from other Not-Intended-For-Circulation (NIFC) coin products by adding novelty elements like lenticular stickers, Swarovski crystals, colorized elements, and non-traditional shapes. The more elaborate the design, the more expensive the coin becomes; the price of the coin having little connection to the coin’s face value.

So if the retail price of the coin has no relationship to the coin’s face value, and if the coin is produced for international consumption and collecting… why carry on the pretense?

Why call it a coin if it really isn’t?

Because an elaborately designed metal object cast in the role of exotic money sells. Nevermind tax considerations and import regulations. Even if the coins being marketed serve as money only in some far away territory all but unknown to the intended consumer, they will still have buyers and they will still sell.

Without the denomination, the object becomes something else: a piece of art, a medal. And as everyone here probably knows, medals don’t (usually) sell as well as coins.

Saturation and the Lack of a Two-Way Market

The United States has the largest market for coins in the world and to limit the scope of my remarks, I will speak only about my first-hand knowledge of the U.S. coin market. But much of what I’m about to say has applications elsewhere. It is my view that for some international coin markets, conditions are actually worse than they are in the U.S.

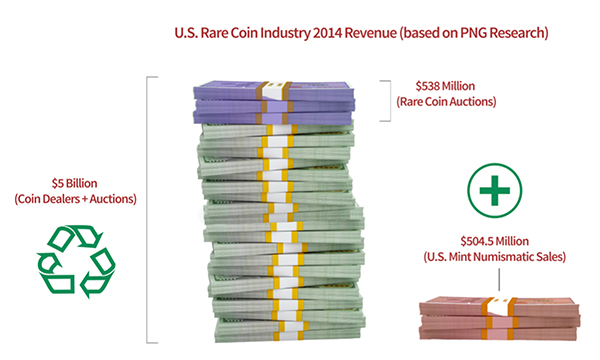

A recent study conducted by the Professional Numismatists Guild (PNG), an international trade organization comprised of coin dealers, puts, by their estimate, the total revenue generated by the rare coin industry in the United States at $5 billion USD in 2014.

This figure does not represent revenue generated by the sale of numismatic coins by the United States Mint. Instead, according to the PNG’s figures, approximately 90% of rare coin industry revenue is derived from dealer-to- dealer and dealer-to-collector sales, while the remainder (approximately 538 million dollars) is generated by rare coin auctions.

A majority of the revenue generated by the rare coin industry is from vintage coins, mostly coins struck in the United States by the U.S. Mint, starting in the 18th century through the first half of the 20th. Ancient coins, rare world coins and American colonial coins struck before the founding of the United States also form a significant portion of the overall market.

At the same time, the United States Mint reported sales of $504.5 million in numismatic items in 2014. This figure is slightly off from the Mint’s 2013 sales figures and 30% off from their peak year, 2011.

Boring down into the U.S. Mint’s sales numbers, we find a total of 5,725,000 numismatic items were sold in 2014 at an average price of $88.12 per unit.

This is a fantastic number.

Essentially, what this number is telling us is that each year the U.S. Mint produces new material at a value of 10% of the traditional coin market. Augmenting this number is the not insignificant amount of revenue earned by world mints and their U.S. distributors, primarily on coins manufactured for the American market.

So, what happens to these coins after the Mint sells them to collectors?

To answer this question, let’s first take a look back, as the situation we find ourselves in has historical antecedents.

In 1965, serial entrepreneur Joseph H. Segel founded the collectible coin business The Franklin Mint. From an initial investment of just $21,000, Segel grew the Franklin Mint into a coin producing juggernaut in the 1970s. Enlisting the help of former U.S. Mint Chief Engraver Gilroy Roberts, the Franklin Mint promised innovation and collectibility, all the while reaching out into markets that the United States Mint, limited by the federal government’s Department of the Treasury to mainly producing circulating coinage, had no interest in.

The effort proved successful at first. Collectors were excited about the prospect of buying precious metals coins with limited production runs. The Franklin Mint offered both novelty items (such as silver art bars) and foreign coins from countries such as Jamaica, Panama, Belize, among others. And while these foreign coins were marketed as legal tender in their issuing countries, the reality was that the coins were issued by the Franklin Mint and struck almost exclusively for American collectors.

In other words, if you are going to go out on the market today to look for a 1978 Jamaica Proof set, you will find it for sale from a collector in the United States, not Jamaica.

This worked for a number of years, and much to their credit the Franklin Mint was successful with both their innovative designs and their business model.

To reinforce the value of the products they offered, Segel and the Franklin Mint promised to make and support a secondary market for these coins. He saw the need to offer collectors the promise that the coins they were selling at significant premiums would hold value in the long term. Segel even shepherded the production of a price guide for Franklin Mint products through a major industry publisher.

Collectors bought into this premise and purchased coins from the company with this understanding.

For reasons that are not clear, Segel and the Franklin Mint never lived up to their end of the deal. The coin industry, not seeing value in Franklin Mint coins beyond the precious metals content, didn’t either.

To their discredit, however–and to the discredit of trade journalism–the Franklin Mint, through aggressive legal tactics, silenced pliant industry media from sounding the alarm.

But it wasn’t long before complaints from Franklin Mint customers compelled CBS television reporter Morley Safer to investigate. The resulting report, which originally aired in 1978, revealed the depths of the public’s fleecing.

Collectors that had spent tens of thousands of dollars or more on Franklin Mint collector coins had lost virtually everything. The face value of these legal tender coins – and their exchange rate against the U.S. dollar – did little prop up their value. The mere mention of the Franklin Mint in conversation today brings up these bad memories, if not also a little ridicule at the Franklin Mint’s expense.

But in what ways is the current manufacture of postmodern collector coins all that different from what happened with the Franklin Mint?

Solutions?

As I mentioned at the beginning of this editorial, the sheer number of new designs is unprecedented in the history of the numismatic hobby.

And while it’s safe to say that a viable market in bullion coins – that is, precious metals coins sold at or near the current market price for their constituent metal – is thriving and supported by a sophisticated network of retailers, wholesalers and consumers, the same cannot be said about precious metals coins that are issued for premiums well above the coin’s intrinsic value.

This is a problem. For coins, unlike cars, computers, or other consumables, do not get used up and discarded. Instead, they are purchased with the belief that they are a store of value and the expectation that this value will increase over time.

Without a proportionally-sized and well-developed secondary market, these goals cannot be realized.

Without a proportionally-sized and well-developed secondary market, these goals cannot be realized.

What I find and what CoinWeek finds is that customers will feel increasingly alienated when it comes time to sell their coins. For example, silver bullion will have to reach prices of $100 or more per ounce to recover the purchase price of many of these coins. For gold coins, gold will have to reach double or triple its current level for these coins to reach par.

Collectors entering the market do not necessarily understand this reality. And those that learn about it the hard way often leave the market. In the long-term this points to a shrinking market.

Solving this problem will not be easy.

For their part, the mints will have to focus their efforts on sustainability. Most mints, I believe, understand this, and in all likelihood would be little affected by a crisis in the modern coin market. Mints that produce dozens or hundreds of coin programs per year, however, would do well to focus some resources on research and the implementation of a viable two-way market – one that provides for some measure of price stabilization of collector coins after the initial sale. It would also be helpful if the mints communicated to their customers the differences between investing in bullion and collecting numismatic coins.

Without such effort, the industry may likely repeat past mistakes. Only this time, they will be multiplied by the sheer scale of the contemporary modern coin minting industry. The rare coin market is built around the recycling of a finite volume of numismatic material. It has neither the thickness nor the resources to consume and prop up the value of all the modern coins struck by the mints today.

The sooner the mints come to understand this new paradigm and do something about it, the more assured the long-term success of their current business models will be.

The most interesting and best coin information in the world! Keep it up!

Well written article. I’ve always stayed away from the “Postage Stamp” countries who issue ‘coins’ depicting everything from Michael Jordan to Disney movies. I’ve often wondered when “Trekkies’ will deluge ANA dealers with their worthless collector coins sometime in the future. Sorry to say, such things do not make future collectors.

What does a country like Nuie need to produce proof coins highlighting American national monuments? For me licensed Family Guy or NBA coins would be more appealing.

Part of the problem, as I understand it, is the symbiotic relationship between tiny entities such as Niue or the Cook Islands and the mints that have product to sell. The mints need their items to be “legal tender” to give them validity as “coins”, otherwise they’re just privately produced commemorative medals. And little countries need an income, which they presumably get, at least in part, from royalties from the sale of “coins” issued in their name. It’s the only reason I can think of for issues from Pacific island countries featuring Russian cars or any of the other themes mentioned in this article.

Perhaps we need a generally agreed set of principles to distinguish these “CLOs” (coin-like objects) from what would have been considered perfectly normal commemorative coins up to about the late 1960s – if there isn’t a tangible connection between the theme and the issuing entity; if the CLOs never actually come near the territory that has lent its name to them; and if there is no collector base (or even human population!) in the supposed place of issue, then perhaps they should be omitted from standard “coin” catalogues for failing to meet these basic criteria.

New Zealand’s Lord of the Rings series, though not to my own taste, would potentially still qualify for inclusion, since the movies were made in that country and have a popular following there. In many other cases, however, we’d have a good way of paring down the “phone book” catalogues for the 20th and 21st centuries using the above three criteria alone.

The consumer needs protection from countries such as UK and Canada that sell “coins” that cannot be redeemed at face value. They should not be allowed to cross the border as they are a fraud.