By Charles Morgan and Hubert Walker for CoinWeek and re-posted …..

In 1963, Coin World columnist and former ANA librarian Ted Hammer wrote about a coin dealer in Texas arrested for trying to sell a gold certificate. The dealer had run afoul of federal authorities who acted to enforce a 30-year-old Executive Order outlawing private ownership of gold coins, bullion, and Gold Certificates. At the time of publication, few in the numismatic community were aware that no crime had actually been committed. One reader was, however, and he began a letter writing campaign that made the Treasury Department change its stance on collectors owning and trading Gold Certificates. That reader’s name was Herbert P. “Herb” Hicks[1].

But before we talk about what happened, let’s take a step back and look at the executive order that started it all, and see whether it still mattered in 1963.

Off of Gold

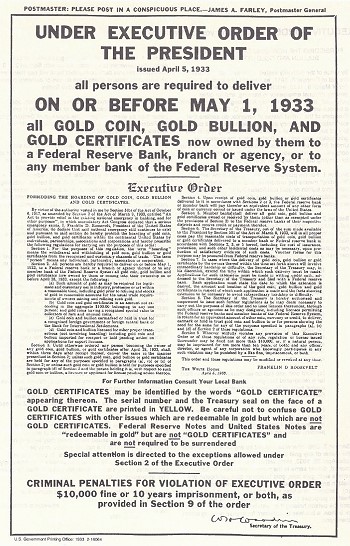

On April 5, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6102. The controversial order is familiar to many who collect gold coins or invest in gold bullion, and is often perceived as an example of tyrannical executive overreach. When the order was announced, the United States was in an intractable financial position. Hard currency standards rendered foreign governments unable to defend their currencies against speculation and unable to capitalize banks, which were failing right and left. In the U.S., Americans faced similar problems – vast unemployment, undercapitalized banks, and the contraction of the banking system. The government needed the flexibility to create money in order to stimulate the economy, and in order to do so, President Roosevelt and his advisors thought that America had to get off of gold.

On April 5, 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6102. The controversial order is familiar to many who collect gold coins or invest in gold bullion, and is often perceived as an example of tyrannical executive overreach. When the order was announced, the United States was in an intractable financial position. Hard currency standards rendered foreign governments unable to defend their currencies against speculation and unable to capitalize banks, which were failing right and left. In the U.S., Americans faced similar problems – vast unemployment, undercapitalized banks, and the contraction of the banking system. The government needed the flexibility to create money in order to stimulate the economy, and in order to do so, President Roosevelt and his advisors thought that America had to get off of gold.

The seizure of privately-held gold was made legal by the Roosevelt Administration’s interpretation of the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917 after the passing of the Emergency Banking Act of 1933. The order was designed and implemented with the help of Republican Treasury Secretary William H. Woodin. The order went into effect in the immediate aftermath of the federally-mandated national bank holiday. Under penalty of harsh fines and potential imprisonment, save for a few specific exceptions, Americans and American institutions handed over their physical gold (including coins) and gold monetary instruments. The government immediately revalued the seized gold, thus devaluing the dollar and beginning the development of modern monetary policy that exists to this day.

It is widely believed that because of Woodin, a notable numismatist in his own right, exceptions were made to the Executive Order, making it possible for numismatists and museums to continue to collect gold coins. The order stated that “gold coins having a recognized value to collectors of rare and unusual coins”[2] were exempt.

Although not spelled out in as many words, the government was clearly allowing coin collectors to hold onto individual specimens of numismatic worth. Even though they were historically significant, and a collector base did exist, Gold Certificates were excluded from this allowance.

Most Americans, desperate to see the country’s financial crisis come to an end, complied with the order. Some challenged the validity of Executive Order 6102, but nobody was able to change the end result. Within a few years nearly all of the Nation’s gold coins, bullion, and Gold Certificates were out of private hands and under government control. A Time Magazine article dated November 27, 1933, noted the only prosecution of a United States citizen for failure to surrender gold. The prosecution failed, but the court upheld the Government’s right of seizure[3].

It would be 30 years before a second prosecution so publicly threatened to take place.

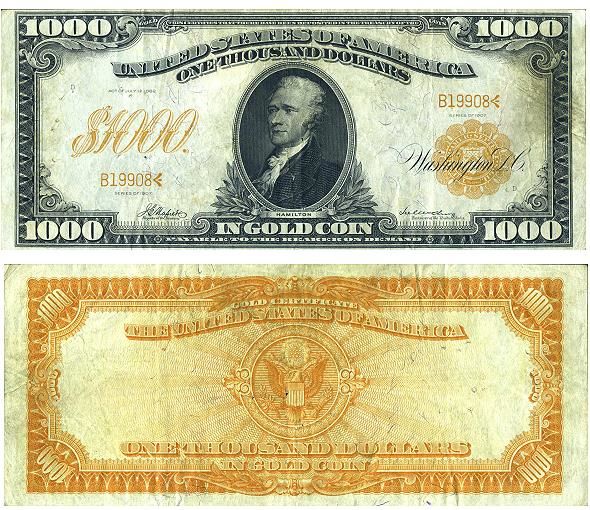

Payable on Demand

As we mentioned above, Gold Certificates were excluded from the protected class of gold numismatic coins. Gold Certificates, in use since 1863, allowed the bearer to receive an amount of gold coin equal to the face value of the note. Since the Federal Government outlawed the private ownership of gold coins and bullion, removing Gold Certificates made a kind of sense because they could no longer serve their original function and perhaps, too, because the government wanted to avoid the political fallout of Americans continuing to see the notes in circulation. And while people surrendered most of the notes in a timely manner, the certificates trickled in for a number of years, with stragglers being redeemed each year well into the late 1950s!

By 1959, the government was ready to end the redemption program for Gold Certificates and other obsolete notes, and wipe its liability for the outstanding notes off of the general ledger. In a letter to the Chairman of the Committee on Banking and Currency, Senator A. Willis, dated March 25, 1959, Vice Chairman C. Canby Balderston wrote that the “total amount of [the] outstanding “old series” Federal Reserve notes… presently is about $37 million”[4]. It became the government’s position that these notes were either “destroyed or irretrievably lost” and, “in the judgment of the Secretary of the Treasury, would never be presented for redemption”[5]. The Act did not demonetize the outstanding notes, but instead freed the Federal Government from securitizing them. In essence, the Treasury didn’t expect to see a considerable amount of old series notes get turned in, and was willing to use the money earmarked for redemption. To wipe the slate clean, Congress passed the Old Series Currency Adjustment Act of 1961.

Interestingly enough, the Treasury granted itself the ability to collect one note from each issue for historical purposes.

A Possible Defense?

In light of the Texas dealer’s dire straits, Herb Hicks considered Gold Certificates legal status after the passage of the Old Series Currency Adjustment Act. Hicks believed that, since Congress had removed the gold backing of all Gold Certificates issued before 1934, the matter of the certificates’ connection to deposited gold was moot. The government recused itself from honoring the certificates in any way besides redeeming them at face value in currently-circulating Silver Certificates or Federal Reserve Notes. Because of this, the Treasury could allow legal ownership without any consequences to the Nation’s gold supply.

He tried to reach out to the dealer but never heard back. He also wrote letters to Charles M. Johnson, Head of the American Numismatic Association (ANA), and to U.S. Representative Philip Philbin (D), who represented Hicks’ home district in Massachusetts.

Johnson expressed support for Hicks’ position, saying, in a letter dated October 31, 1963:

“I have read with considerable interest your three page summary and study of the gold laws and gold certificates… You have raised several worthwhile points of interest to our hobby of numismatics. I hope you will pursue this matter further.”[6]

Congressman Philbin wasn’t so sure, explaining that matters of fiscal and monetary policy were complicated and best left to the experts [our emphasis]. Even still, Philbin pursued the matter with the Treasury Department on behalf of Hicks and for his own personal knowledge.

Stonewalled

On December 13, 1963, Hicks got his first reply. It was from the Director of the Office of Domestic Gold and Silver Operations at the Treasury Department, Mr. Leland Howard, who wrote:

“The present status of United States Gold Certificates is governed by the Order of the Secretary of the Treasury of December 28, 1933, as amended and supplemented, and the Instructions of the Secretary of the Treasury of November 17, 1934… This order and the Instructions require that all Gold Certificates be delivered to the United States for redemption, a requirement which is still in force.”[7]

Furthermore, Howard found “no record that any authority was ever given to anyone to hold [Gold Certificates] as collectors’ items”, noting that such an accommodation was made for United States and foreign numismatic coins. Speaking for the Treasury Department, Howard felt that there was no “substantial educational or numismatic need to be served by permitting the widespread acquisition of [Gold Certificates] by collectors.”[8]

This response was ignorant of the fact that obsolete notes were indeed collectors’ items, and had been since their introduction (the prevalence of Colonial era currency clearly attests to a long tradition of paper money collecting), and the fact that the Treasury Department was granted the privilege to collect examples of redeemed obsolete currency notes in the Old Series Currency Adjustment Act of 1961. Not to mention the fact that some percentage of the outstanding Gold Certificate notes were secretly held by collectors who knew they could be prosecuted or forced to surrender their notes and face a substantial fine if they publicly signaled that they had them (by trying to sell them, for example).

This response was ignorant of the fact that obsolete notes were indeed collectors’ items, and had been since their introduction (the prevalence of Colonial era currency clearly attests to a long tradition of paper money collecting), and the fact that the Treasury Department was granted the privilege to collect examples of redeemed obsolete currency notes in the Old Series Currency Adjustment Act of 1961. Not to mention the fact that some percentage of the outstanding Gold Certificate notes were secretly held by collectors who knew they could be prosecuted or forced to surrender their notes and face a substantial fine if they publicly signaled that they had them (by trying to sell them, for example).

The fact that Secretary Woodin didn’t allow for the collectability of Gold Certificates seemed like an oversight rather than a purposeful omission. He was well aware of the motivations of collectors and notaphilists. Perhaps the Government would have been better off setting a deadline for their use as legal tender instead of criminalizing their possession. Such an announcement would have likely had the desired result.

For his part, Representative Philbin asked for clarification from the Treasury Department concerning the issues that Hicks had presented.

On January 28, 1964, Director Howard replied to Representative Philbin, stating:

“Gold Certificates are obligations of the United States, which, until all in the hands of the public were required to be delivered in 1933, were fully redeemable in gold.

“As I said in earlier correspondence, the value now attributed to Gold Certificates is derived from the fact that practically all were duly turned in to the Government by law-abiding citizens in 1933. We believe that few persons, if any, held these certificates as part of a collection at that time. This is the primary reason they were not exempted, as were coins.”[9]

Essentially, Mr. Howard’s position was that if the notes were outlawed, then only outlaws would still own them. Nevertheless, he acknowledges that what gives them value – numismatic value – is the fact that most of them were turned in and destroyed, an obvious and logical development that Woodin and the Roosevelt Administration should have seen coming. That being said, the Treasury Department gave no indication that it was willing to reverse course, despite the fact that Gold Certificates no longer posed a threat, psychological or otherwise, to the monetary system of the United States. They remained illegal.

Resolution

As far as Hicks knew, the whole thing was going nowhere. His letter writing campaign resulted in some confusing but altogether typical responses from the Federal Government, which gave him little hope that they’d change their minds. Imagine his surprise when he learned that someone within the halls of government had finally seen the light.

A Treasury Department memo dated April 24, 1964 took a position suspiciously similar to the letters he thought were dismissed out of hand. In this memo, the Department removed all restrictions on the holding and acquisition of Gold Certificates issued by the United States Government prior to January 30, 1934. As of this point forward, collectors were allowed to legally hold Gold Certificates. The Texas dealer was now off the hook, and other dealers and collectors clandestinely holding these notes could openly buy and sell them. The Treasury agreed with Hicks’ argument, that the law was no longer necessary because the notes were no longer redeemable in gold but could, if so desired, be exchanged at face value for any other currency of the United States[10].

America’s only illegal currency was legal again.

Representative Philbin told him the good news. Mr. Philbin felt that the action was “prompted in some measure by [Hicks’] persistent efforts and persuasive arguments to get the regulations changed for the benefit of collectors.”[11] Although Mr. Hicks didn’t get any public credit for his efforts, the power of his ideas still carried the day. He doesn’t recall what happened to the dealer in Texas, or if the normalization of Gold Certificates had any effect on the gentleman’s legal situation. What he does know is that the Treasury Department’s easement of restrictions on Gold Certificates meant that a generation of currency collectors could now lawfully pursue the study and collection of an important historical issue. If you’ve seen one of these notes in person, it’s because of Herb Hicks.

* * *

Notes

[1] Authors’ note: In our estimation, Herb Hicks is one of the great unsung numismatists of the 20th century. Without seeking attention for himself, Hicks has been instrumental in the research and discovery of Eisenhower dollars and Washington quarters, among other series and topics. We hope to bring you more about Hicks in the future.

[2] http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=14611&st=&st1=. Web. Accessed 1/15/2013.

[3] Time Magazine. 27 Nov. 1933. Print.

[4] http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/docs/historical/senate/senate_frdp_old1960.pdf . Web. Accessed 12/18/2012.

[5] Ibid., 11.

[6] Letter dated October 31, 1963 to Mr. Herb Hicks from Charles M. Johnson, Board of Governors, American Numismatic Association.

[7] Letter dated December 13, 1963 to the Honorable Philip J. Philbin from Leland Howard, Director, Office of Domestic Gold and Silver Operations.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Letter dated January 28, 1964 to the Honorable Philip J. Philbin from Leland Howard, Director, Office of Domestic Gold and Silver Operations.

[10] United States. Department of the Treasury. “TREASURY REMOVES RESTRICTION ON UNITED STATES GOLD CERTIFICATES ISSUED BEFORE 1934”. Memo. 24 April, 1964.

[11] Letter dated May 6, 1964 to Herb Hicks from Philip J. Philbin, 3D District, Massachussetts.

References

http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=14611&st=&st1=

http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/topics/?tid=89

http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Page:United_States_Statutes_at_Large_Volume_75.djvu/186

* * *

FLIP OF A COIN™

What can I get for two beavers?: Conducting trade with America’s indigenous peoples was necessary for the survival of many European colonists in the New World. One common commercial instrument was the use of animal skins. The exchange of goods for these skins was called peltry.

Stoppers vs. Key Dates: In a series, there exist one or more issues that are more expensive than the rest. These coins may or may not be out of the price range of most collectors, but are within reach of those with patience and determination (the 1909-S VDB, for instance). If you want to put together a complete Lincoln cent collection, you will likely find a way to get this key date coin. A stopper, on the hand… well, this is a special kind of coin that transcends key date status. Stoppers are the 1913 V Nickels, 1933 Saint-Gaudens double eagles, and any number of elusive-to-unique colonial issues.

Germans spent marks. Did you know we almost did, too? Before the dollar was settled on as the basis for the federal monetary system, several alternatives were under consideration. One was devised and proposed by Robert Morris and Gouverneur Morris (no relation) that was valued at 1,000 units and called a Mark. Only one example is known to exist.

* * *

Great article, well written and researched. Never knew about this. Thank you.

You’re very welcome, thanks for reading.

great article

I was given one of these 20 years ago by my elderly neighbor when I was about 12. It’s a $20 certificate and I recently realized it’s a star note as well. He was a ww2 vet and a great guy, I found out recently that it was by far the most valuable thing in his modest coin collection.