by Joshua T. Herbstman for CoinWeek….

At some time or another, we have all gotten an email that resembles the following:

Dear Sir,

During the regime of our late head of state, General Sani Abacha, the government officials set up companies and awarded themselves contracts which were grossly over-invoiced in various Ministries.

The new civilian government set up a Contract Review Panel and we have identified a lot of inflated contract funds which are presently floating in the Central Bank of Nigeria. However, due to our position as civil servants and members of this panel, we cannot acquire this money in our names.

I have therefore, been delegated as a matter of trust by my colleagues of the panel to look for an overseas partner into whose account the sum of US$31,000,000.00 (Thirty one Million United States Dollars) WILL BE PAID BY TELEGRAPHIC TRANSFER. Therefore we are writing you this letter today…

I must solicit your confidence in a most valuable transaction. This is by virtue of its nature as

being utterly confidential and top secret.

And henceforth the scam goes along something like this: the recipient must wire funds to some foreign agent to process the transfer of said funds. Then a bank will release the money and everyone will walk away with a share of the aforementioned $31 million.

Or so it’s supposed to go. And by now you undoubtedly know how this story always ends.

It would be comforting to think that in our information-rich modernity, such brazen cons would be nearly impossible to achieve. One need only Google a few terms or contact any number of authorities to scrutinize such suspect a proposition. Why would anyone fall victim to this most obvious of crimes?

But they do, and in staggering numbers. Complicating the matter further is that victims are often reluctant to come forward to authorities in time (if at all) due to feelings of shame and guilt over being conned. Nigerian email schemes are but a small part of the mosaic of Internet fraud, which the FBI estimated cost Americans some $500 million in 2010 alone. Worldwide, online fraud in all of its forms is now estimated to cost the global economy hundreds of billions per year.

To be sure, there are cons in almost every conceivable area of life. That is certainly true of numismatics. Fake coins and counterfeit notes have been around for centuries. And in the world of scripophily, there is now a 21st century scam using worthless paper from the 19th and 20th centuries. The fraud involves the defaulted sovereign bonds of China, Mexico, and Russia, among other nations. On occasion it will even use American railroad bonds from the 1800’s. But no matter the security used in the deception, to prosecutors and law enforcement officials alike, the scam is known as historical bond fraud. The premise of the fraud is this:

There are many nations and indeed corporations out there that have issued debt that traded in the international markets. Some of these entities have stopped paying on their sovereign (or) corporate obligations, and owe interest and principal to their bondholders. These overdue funds are often denominated in terms of the price of gold, and moreover, in the price of gold decades ago when the bonds were issued. So with compounded interest, along with the historic rise in the price of gold, these securities, available at a discount, should be worth a fortune today!

Sounds a bit sophomoric, no? But the explanation goes on with language like this:

In terms of international law, when governments change, they are not permitted to simply repudiate the obligations of past administrations, however much they may disagree with the politics of the prior regimes. If this were the case, no one would ever loan money to any country. Therefore these bonds must be valid obligations. As they have a value to them, there are several international trading platforms that you can deposit your bonds into for collateral, turning them into hefty profits!

An explanation is then proffered on how these “trading platforms” are backed by the IMF, the World Bank, NYSE Euronext, Luke Skywalker and the Rebel Alliance, or whomever else they can think of to add to their bouillabaisse of bullshit.

In one online solicitation, the fraud promises that a portion of the profits will go directly to UN human relief programs. And that is only fair of course, because in this particular exchange, it is the UN itself that is running the trading program for the benefit of the international investors:

The bonds will be leveraged 20 times, roll over 40 times and payable every 2 weeks for 10 years. The profit will be paid to the bondholders at 20%; the United Nations will keep 80% for humanitarian projects and repatriate countries for losses incurred with these debt instruments.

Of course, the UN does not run any international bond redemption programs, and the use of a charitable purpose only makes such scams more appealing and thereby harmful. Many governments and financial institutions have issued warnings regarding this type of fraud, but these often go unnoticed. And so investors and collectors alike are duped into overpaying for worthless debt certificates.

All bonds are equal; some are more equal

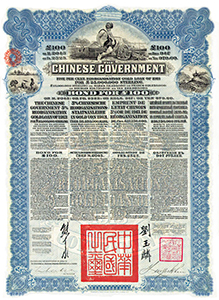

Some of the most common bonds used in historical bond fraud are the various debt instruments of both the governments of Imperial China and its successor, the Republic of China.

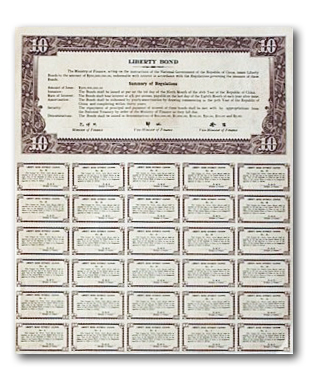

From railroad expansion to wartime “Liberty Bonds,” China tapped international markets through various bond offerings. Banks such as HSBC and J.P. Morgan helped sell these securities to Western markets, on the promise of course that the Chinese government would repay their sovereign obligations. But two World Wars and a domestic crisis leading to the Chinese Civil War would drastically change any promise of repayment. On October 1, 1949, Mao Zedong declared the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, also known as the PRC.

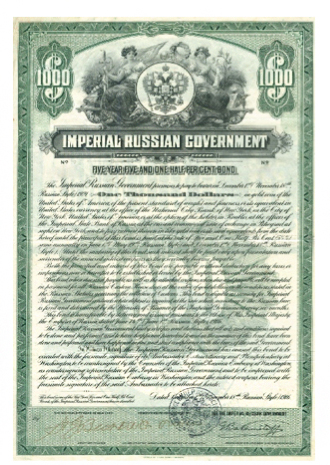

One of the first acts of the new communist government was to repudiate the debt accumulated by previous Chinese regimes. Such repudiation was common for communist governments in the 20th Century. The government of the USSR repudiated the debt of Imperial Russia in 1917, and the Castro regime repudiated the debt of Batista’s Cuba in 1960.

As investments go, sovereign bonds such as the aforementioned were considered attractive investments to many foreigners in the West. British and American citizens bought large amounts of Chinese debt, while many French citizens bought the “Czar Bonds” of Imperial Russia. It is estimated that by the time of the Russian revolution, one in two French households owned Russian sovereign paper. And like China, radical political upheaval, revolution, and regime change brought with it a repudiation of current outstanding bond debt.

Of course the story doesn’t end here, for if it did it would be just your run of the mill sovereign debt default. Such a scenario has played out numerous times throughout world history. In the cases of China and Russia, payment on certain bonds, owned by a certain classes of investors, was eventually to come albeit decades later. These specific one-time repayments have given a false sense of hope to some investors, and a fraudulent marketing ploy to some con artists. Also worth noting is the fact that legal challenges in to these sovereign defaults in no way facilitate any sort of future repayment by these governments. A court of one country can order payment of debts by another, but such verdicts are routinely ignored.

Communist China chose to repay certain bondholders of its disavowed imperial debt. To maintain access to British financial markets, (and perhaps with the future return of Hong Kong in mind), China agreed in 1987 to pay British holders of its 1913 5% Reorganization Gold Loan bearer bonds, notes which many other bondholders around the world still hold today as defaulted paper. In debt finance, such a step is highly improper and is a type of selective default. Bondholders are not to be treated differently based on their nationality or country of residence. Either the 1913 5% “Reorgs” were a valid obligation to be honored, or they were not.

In the case of the Russia’s 1917 default, settlement negotiations for partial payment on the securities began in 1997. By 2000, an agreement had been reached whereby French bondholders could receive up $12,500 per claim for their redeemed bonds, sometimes a fraction of an original investment. The total settlement Russia offered was around $400 million, which is significantly less than the billions invested by French and other European investors.

Russia had come to a similar arrangement with the British government back in 1986. Britain had long seized Soviet-era assets held there after the USSR failed to pay the $75 million it owed to British investors. This figure was later estimated to be about $1.3 billion in terms of a 1986 exchange rate valuation. (The Russians for their part claimed the value of the assets seized by Great Britain far exceeded the debt payments it owed. The British government however disputed such inflated Russian assertions.) In response to the seizure, the USSR subsequently seized British assets and property within the Soviet Union.

The ultimate settlement allowed British investors to recoup some $600 million in lost property and bond repayments, and provided each government a way to cancel their claims against each other. The British government’s own holdings of Czar Bonds were not repaid as part of this agreement.

The Mechanics (and Morality) of the Fraud

You may be wondering how exactly historical bond fraud works. The specifics for transactions can and do vary, but there are unmistakable hallmarks to this scam. And unfortunately many victims are proactive participants in their own dubious con.

Whether through Internet chat boards, email solicitations, or direct in-person conversations, the pitch to invest in defaulted bonds is quite insidious.

A story is presented that tells of great returns on old historic securities, many of them sovereign issues of foreign governments. As these bonds are payable in gold, at current prices, these securities are quite valuable as the principal and interest payments have compounded over years of non-payment. When one adds in the rise in the price of gold, these certificates are worth a fortune in today’s dollars.

Certain collectibles dealers are finding the sale of these defaulted securities very lucrative. To be sure, they themselves never promise any marketability or negotiable value to the bonds. Disclaimers are given, and buyers are informed they are purchasing a collectible only. And on the surface, this caveat emptor may seem like the seller is adequately covering his part of the transaction.

Many old bonds are collectible, and although they have no negotiable value as investments, are wonderful treasures of history. But most of this defaulted debt is not rare and never counterfeited, which makes the next part of this tale all the more insidious.

When it comes to the fraud, buyers and sellers now often include third-party authentications of bonds. But history clearly shows these securities are not counterfeited. There are the occasional stories that have made the news, but they are of counterfeited U.S. Treasuries, not defaulted Chinese or Mexican bonds from 80 years ago. Sellers use the authentication to enhance these bonds, which in turn lead to buyers now requiring it when buying such certificates. Within this fraud, it is now taken for granted around the world that these worthless bonds need to have a pedigree to be transacted.

Consider this: No one bothers to authenticate, let alone grade, defaulted Confederate bonds. Why is that? Well, who has the chutzpah to actually represent that the South will rise again and its debt obligations will finally be paid off? Collect them? Sure. Frame them? Why not? But authenticate defaulted CSA debt certificates… Why would you even bother to spend the money?

This fraud is wrought with other specious terms that accompany a sale.

Dealers often black out the serial numbers of the certificates, as if keeping them a mystery preserves their marketability or freshness.

To the educated collector, this premise is of course patently absurd. The rarest collectibles in the world are photographed, catalogued, auctioned, and sold with serial numbers in full public display. (To be sure, certain items, such as popular Swiss watches subject to frequent counterfeiting, often have serial numbers blocked out when sold online.) But in numismatics it is unheard of.

A 1913 Mexican “White Dove” bond is not a Rolex.

And when it comes to bonds the logic makes no sense. Securities that have no history of counterfeiting should not need to have their serial numbers protected.

Besides, aren’t these bonds accompanied by the aforementioned third-party authentications? And public knowledge of a particular bond number in no way compromises the value of a bearer security. It is either money-good or not. The blocked out numbers are merely another clever trick, one to reinforce a false narrative to buyers. These bonds must be valuable ‘less why would their serial numbers be so closely guarded?

Many transactions go even further beyond the protected serial numbers and third-party authentication requirements. Some parties will require a “hostage photograph” with their transactions- meaning the bonds along with the third-party paperwork must be photographed with a currently dated newspaper. One can only wonder why Heritage and Stack’s have not employed such a useful tool of verification.

As mentioned earlier, global institutions such as the World Bank and the IMF are routinely promoted as the end facilitators of these debt transactions. The fact that no trading platform has ever or will ever exist at these institutions is lost on victims. Also lost is the clear warning posted online by the U.S. Treasury Department about this scam. It is hard to fathom how people would overlook such an easy verification in our age of Google. And any reputable securities broker would verify that defaulted bearer bonds have no collateral value in an investment account- let alone even being allowed for deposit in the first place.

And what also escapes victims is the most obvious of observations: If these historical bonds could somehow be collateralized and traded in international markets for huge profits, why would they be available on eBay or from a dealer at a discount? Wouldn’t investment professionals have long ago bought up this debt to reap such gains?

Yet victims are led to believe they will be opening investment accounts with greatly appreciated assets serving as collateral. In reality however they find themselves holding worthless paper that, in the world of scripophily, usually has little collectible value as well. While dealers may not themselves be breaking the law, they are benefiting from the deliberate manipulation of others who are doing just that.

And so the only people profiting here are those selling the worthless securities at inflated prices, authenticating the certificates for others to trade, and promoting these bonds as a legitimate investment. The exact same certificates one could find cheaply on eBay or in a bargain bin at the FUN Show are being sold for thousands of dollars. Such precipitous differentiations cannot be dismissed away as a normal retail markup. The same dealers would never pretend to sell Confederate bonds or other common defaulted issues with such rapacious profits. And they know there are con artists out there who have hyped up the market for these worthless securities.

To pretend that a defaulted Mexican bond signed by Santa Anna is either very rare or has some investment value (beyond being an autographed collectible) is dishonest.

To pretend that a defaulted Mexican bond signed by Santa Anna is either very rare or has some investment value (beyond being an autographed collectible) is dishonest.

That defaulted securities, with no history of counterfeiting, would need third-party authentication also strains credulity. Of course careful sellers are sure to make no investment representations about these bonds, as that would violate U.S. securities law. But their actions are directly contributing to the food chain of historical bond fraud.

A man who opens up a hypodermic needle booth in the worst crime-ridden area of town doesn’t evade moral responsibility simply because he is not selling the heroin himself to strung-out junkies. Although few in number, the dealers and authenticators involved know the end-use purpose of these bonds, and the existence of these scams.

A $500 “Santa Anna” bond issued in 1886 to raise funds for the exiled Mexican leader. Please note that while the United States of America is prominently engraved on this security, it relates to where this debenture was issued, and is no guarantee of value by the U.S. government.

But if dealers are not directly promoting the investment scams, who is, and how are they making any money off of this? This part of the equation is more difficult to trace, as the fraud solicitations are initially couched in ambiguous terms. Solicitations are usually done online by dubious fly-by-night characters that come and go from the scene. And there are no doubt those who are charging fees to “process” the securities, although such fees are never disclosed upfront.

This said, historical bond fraud makes up a tiny fraction of the crime found today online. The story presented here is not one of involving billions in losses. But the numismatic community should bear some responsibility in directly addressing such a well-established and known fraud. Of course scripophily dealers should make profits, and no one should be casually dictating to them how to run their businesses. Old stocks and bonds can be wonderful collectibles, and some have a real rarity to them. But the securities mentioned here do not have such attributes beyond being relatively common (and thus reasonably priced) collectibles in today’s market.

When researching this subject matter, a well-respected currency dealer posited a simple question: What would the man who just sold you that collectible buy it back from you for?

Caveat emptor, as the famous Latin admonition goes. Buyer beware. There is a popular Yiddish saying worth remembering too: A halber emes iz a gantser ligen. A half-truth is a whole lie. Honest dealers respect the hobby, their clients, and hopefully, themselves.

About the author

Joshua Herbstman is a portfolio manager based in Florida. He holds an MA in history from Georgia State University. He is an avid collector of U.S. Treasury bonds, and is currently working on cataloging the history of U.S. Treasury securities along with an online census for Treasury debt collectors. He can be reached at [email protected]