By Mike Markowitz for CoinWeek …..

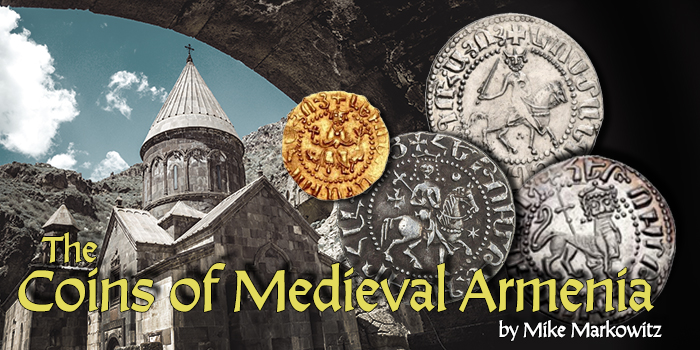

THE CILICIAN KINGDOM OF ARMENIA (1199 – 1375) produced a vibrant culture strongly influenced by interaction with neighboring Crusader states[1]. Wealth derived from trade between East and West led to an extensive royal coinage that includes some of the most handsome and popular medieval coins collected today.

Cilicia[2] is a mountain-ringed region of southern Anatolia (now largely the Turkish province of Adana). Ruled in succession by Hittites, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, and Byzantines, it became home to increasing numbers of Armenians fleeing Muslim domination in their Caucasian homeland during the 11th century. Armenian warlords carved out semi-independent baronies based around hilltop fortresses. Two rival noble families emerged: the “Roupenids” and the “Hetoumids”. Some of these barons (c. 1080 – 1198) struck rare copper small change for local use.

Levon I

On January 6, 1199, a Roupenid prince named Levon (or Leo – Cilician personalities are variously known by their Armenian names and the Latin or “Frankish” equivalent, and there are many variant spellings) was crowned as king at Tarsus, with the approval of the German emperor Henry VI and the blessing of both the Pope and the head of the Armenian Church.

More recent scholarship attributes these coins to Levon III, who ruled from 1289 through 1307 (Vardanyan, 130). This is a common problem in medieval numismatics, where multiple rulers bear the same name, and sequence numbers were not used in inscriptions.

Levon reigned for over 20 years and his royal coinage is complex. He moved the capital and the main mint to the hilltop fortress of Sis (near modern Kozan, Turkey). The so-called “coronation” issue[3], a tram weighing just under three grams[4], bears an unusually ambitious image (medieval die cutters rarely had the skill to tell a story pictorially). Levon kneels before the Virgin Mary, her hands raised in prayer, while a ray of light shines down from above. The reverse is a pun on his name; “Leo” means lion. A crowned lion holds a double-barred “patriarchal” cross. A more common reverse shows a pair of lions, back to back. There were rare double trams, and occasional half trams (about 1.5 grams)[5]. There was even a “half double tram” struck to a slightly different weight standard for uncertain reasons.

For the obverse, Levon’s engravers copied the design of emperor Henry VI’s contemporary imperial coinage: crowned ruler enthroned holding a scepter in the form of a lily, and an orb topped by a cross. These lightweight silver coins (known today as “bracteates”) were struck on such thin blanks that the design appears on both sides[6].

A disappointment of Levon’s reign was his failure to conquer the strategic city of Antioch from Prince Bohemond IV (reigned 1201 – 1216). Some rare Crusader-style deniers in debased silver alloy (“billon”) inscribed in Latin rather than Armenian were struck in anticipation of this conquest. The obverse bears a crowned head, and the reverse bears a cross. The inscription reads “Leo, by the Grace of God / King of the Armenians.” The only example to appear at auction recently brought over $4,000 USD in a 2010 US sale[7].

There are very rare gold tahekans[8], probably based on the weight standard of the contemporary Islamic dinar. A unique half tahekan[9] brought $40,000 in a 2016 US auction. Bedoukian argues that “these were not struck for circulation, but rather as gifts that were distributed on special occasions” (50). Some collectors doubt the authenticity of the Cilician gold coins that have appeared on the market.

The small change consisted of copper tanks weighing about seven grams[10]. The obverse bore a crowned lion, and the reverse a patriarchal cross between two stars. Abundant copper coinage in the medieval era is usually evidence of a vigorous urban economy, where people need to make small daily purchases, such as a loaf of bread.

After reigning 34 years, Levon died in 1219 aged about 69, leaving a three-year-old daughter, Zabel (“Isabella”) as heiress. One regent was assassinated, and another arranged a political marriage between the child Queen and Philip, son of Bohemond IV of Antioch. Philip proved so offensive to Armenians that he was imprisoned and poisoned (1226). Zabel was then forced to marry the regent’s son, Hetoum (or Haython), uniting the kingdom’s two noble families.

Hetoum I

Trams of Hetoum and Zabel, well-struck, in good silver, survive in abundance[11]. On the obverse, the couple stands together holding a long cross between them. Typically for male-dominated medieval society, no coins of this long reign name the queen in the inscription. The crowned lion appears on the reverse.

A major threat to the kingdom was the neighboring Seljuq Turkish Sultanate of Rum. To secure a peace treaty in 1228, the Armenians agreed to accept Sultan Kaykhusraw as their nominal overlord, and issued a handsome series of “bilingual” trams[12], showing Hetoum on horseback on the obverse, and an Arabic inscription on the reverse proclaiming “The Supreme Sultan, Helper of the World and the Faith, Kaykhusraw ibn Kayqubad”. Hetoum’s copper coinage consisted of a large tank weighing nearly eight grams[13], and its half, the kardez.

With the kingdom facing threats from Muslim Turks to the north and the Fatimid Caliphate (and the Crusader states) to the south, in 1247 Hetoum made an alliance with the Mongols. Mongol Khans generally tolerated all religions, as long as subjects paid tribute[14]. Hetoum’s brother, Smpad (or Smbat), made the long trek to Karakorum in Mongolia to pay homage to Güyük Khan (reigned 1246-1248, grandson of Genghis Khan). In 1254 Hetoum traveled to meet Möngke Khan (reigned 1251-1259), who had conquered much of Iraq and Syria. Armenian armored cavalry fought alongside the Mongols in many campaigns. After Cilicia was invaded and ravaged by Egyptian Mamluks, Hetoum abdicated in 1270, retiring to a monastery, and his son Levon II took the throne.

Levon II

Levon II became king at the age of about 34 and ruled for 19 years. His wife Keran (or Guerane) bore 14 children, including five sons who would, in turn, become Armenian kings. A daughter, Rita, married the Byzantine emperor Michael IX Palaeologos. In 1271 Marco Polo passed through the Cilician port of Ayas on his epic journey to China. Levon II’s trams followed the design of his father’s coins: the king on horseback, with a crowned lion on the reverse[15]. Trams of Levon II are scarce; it appears the alloy was gradually debased over the course of the reign, “wide variations in the silver content made transactions difficult, and that most of his silvers were eventually melted to make the more uniform coins of his successors” (Bedoukian, 54).

Hetoum II

Eldest surviving son of Levon II, Hetoum II, aged about 23, reluctantly took the throne upon his father’s death in 1289, although he much preferred the life of a monk. He abdicated twice, once in 1293 and again in 1296, in favor of younger brothers. His coinage consists of poorly struck billon deniers[16], similar to contemporary Crusader issues, and copper kardez, “possibly the most carelessly executed coins of the Roupenian dynasty. The lettering is seldom legible and quite often the die has been struck off center” (Bedoukian, 89). In 1307 Hetoum, his nephew King Levon III (aged 18) and about 40 Armenian nobles were treacherously murdered at a banquet by Bilarghu, a Mongol general who had converted to Islam. When Mongol Khan Oljaitu (reigned 1304 – 1316) learned of this treachery, he had Bilarghu and his troops executed.

Smpad

Smpad (or Smbat) seized the throne in 1296 while his brothers Hetoum II and Thoros were visiting their sister, Empress Rita, in Constantinople. He murdered Thoros and had Hetoum partially blinded. Rare silver trams of Smpad’s brief reign are similar in style to those of Levon I; many were probably melted down to erase the memory of the rebel king. Smpad was overthrown with the aid of another brother, Gosdantin, when Hetoum regained his sight.

Gosdantin

“Gosdantin, the fourth brother, was outraged by Smpad’s behavior, and gathered an army to confront him. A pitched battle was fought near Sis, the royal capital, in which Gosdantin was victorious. Smpad was thrown into prison and with Hetoum’s permission, Gosdantin became king of Armenia in 1298 (Saryan, 202).”

Gosdantin celebrated his victory on magnificent double trams. On the obverse the king on horseback holds a sword; on the reverse, he stands with a sword in one hand and a cross in the other. The unfamiliar image of the king holding a sword was a remarkable innovation, recalling the coinage of Byzantine emperor Isaac Comnenus (reigned 1057 – 1059). Only a few examples are known; one realized almost $26,000 in a 2018 auction[17].

In 1299, Hetoum II returned to the throne. When Gosdantin plotted to restore Smpad, he was jailed for the rest of his life.

Oshin

Oshin was the last of Levon II’s sons to rule Armenia. He became king when his nephew Levon III was murdered in 1307. His rare, high-quality silver trams (sometimes described as a “coronation issue”) were the last examples of this denomination[18]. They show the king enthroned, with the hand of God reaching out from the left to bless him. Early in his 13-year reign, these trams were replaced by the takvorin in a grayish low-grade silver alloy[19]. Oshin’s small copper poghs (about 1.5 grams) are scarce.

Guy

“During his short reign of only two years, Guy had little time to issue coins in large numbers … his silver coins are quite rare (Bedoukian, 95).”

Guy de Lusignan reluctantly accepted the crown when his cousin Levon IV was murdered by Armenian barons. Guy then took the name Gosdantin II. A capable military leader, he refused to pay tribute to the Mamluks, but he aroused so much resentment by promoting French-speaking courtiers that he was assassinated (April 17, 1344). A rare copper pogh of King Guy brought $2,100 in a 2010 auction[20].

Levon V

The tragic last king of Cilician Armenia was born about 1342 on Cyprus to the aristocratic House of Lusignan, which ruled that island and was related by marriage to the Armenian ruling dynasty. He was elected to the throne after his cousin Gosdantin IV was murdered in 1373. The kingdom was in desperate straits, repeatedly invaded by Turks and Mamluks, most trade in the hands of Venetian and Genoese merchants, and society wracked by civil strife between Roman Catholic and Armenian Apostolic factions. Mamluks captured Sis in 1374, and King Levon V surrendered the last castle on 16 April 1375. Taken to Cairo as a prisoner, he was eventually ransomed by King Juan I of Castile (reigned 1379 – 1390) and lived out the rest of his life in exile in France, dying in 1393. Levon’s rare coinage consists of wretched little billon deniers (about half a gram[21]), bravely inscribed “Levon, King of All the Armenians”, and a few copper poghs.

* * *

Notes

[1] See www.coinweek.com/world-coins/medieval-numismatics-coins-of-the-crusaders

[2] The common English pronunciation is sil-ISH-ya. The Greek pronunciation, kil-ik-KEE-ya is also correct.

[3] CNG Auction 97, 17 September 2014, Lot 905. Realized $1,000 USD; estimate $200.

[4] The word “tram” or “dram”, related to the Greek drachma and Arabic dirham, is still used for the modern currency of Armenia ($1 USD = 474 AMD).

[5] CNG Auction 46, 24 June 1998, Lot 722. Realized $200 USD.

[6] Nomos Auction 14, 17 May 2017, Lot 501. Realized $174 USD.

[7] CNG Auction 85, 15 September 2010, Lot 100. Realized $4,100 USD; estimate $1,250.

[8] Spink Auction 13012, 26 March 2013, Lot 180. Realized UK£1600 ($2,425 USD); estimate UK£2,000-3,000

[9] CNG Triton XIX sale, 5 January 2016, Lot 2219. Realized $40,000 USD; estimate $50,000

[10] CNG Electronic Auction 407, 11 October 2017, Lot 652. Realized $120 USD.

[11] CNG Auction 85, 15 September 2010, Lot 102. Realized $310 USD.

[12] Stephen Album Auction 34, 23 May 2019, Lot 561. Realized $400 USD; estimate $200 – 240.

[13] Nomos AG, obolos 6, 20 November 2016, Lot 1091. Realized $89 USD.

[14] See www.coinweek.com/ancient-coins/coinweek-ancient-coin-series-coinage-mongols

[15] Leu Numismatik Web Auction 2, 3 December 2017, Lot 963. Realized $97 USD.

[16] Leu Numismatik, Web Auction 2, 3 December 2017, Lot 965. Realized $112 USD.

[17] Leu Numismatik Auction 3, 27 October 2017, Lot 362. Realized $25,964 USD; estimate $7,500.

[18] Leu Numismatik, Web Auction 6, 9 December 2018, Lot 1520. Realized $605 USD.

[19] CNG Triton XIII, 5 January 2010, Lot 1727. Realized $500 USD; estimate $150.

[20] CNG Auction 85, 15 September 2010, Lot 126. Realized $2,100 USD; estimate $1,000.

[21] CNG Auction 85, 15 September 2010, Lot 128. Realized $320 USD; estimate $300.

References

Bedoukian, Paul Z. ‘The Coinage of Cilician Armenia’, American Numismatic Society NNM 147. New York (1962)

Bournoutian, George. A Concise History of the Armenian People. Costa Mesa, CA (2006)

Der Nercessian, Sirapie. “The Kingdom of Cilician Armenia”, A History of The Crusades. Philadelphia (1962)

Evans, Helen C. (editor). Armenia: Art, Religion and Trade in the Middle Ages. New York (2018)

Malloy, Alex, Irene Preston and Arthur Seltman. Coins of the Crusader States (2nd edition). Fairfield, CT (2004)

Macler, Frederic, “Armenia”, The Cambridge Medieval History, Vol. IV. Cambridge (1923)

Metcalf, D. M. “Notes on the classification of the trams of Cilician Armenia”, Numismatic Chronicle 141. (1981)

Nercessian, Y. T. Armenian Coins and Their Values. Armenian Numismatic Society, Los Angeles (1995)

Saryan, Leon. “Analyzing Armenian coin values”, The Celator 12. (October, 1998)

Saryan, Leon. “An Unpublished Silver Double Tram of Gosdantin I (1298-1299), King of Cilician Armenia”, American Journal of Numismatics 12. (2000)

Vardanyan, Ruben. “Corrections to deep-rooted errors in the attribution and classification of coins of the Cilician Armenian kingdom, part I”, Armenian Journal of Near Eastern Studies 12. (2018)