By Tyler Rossi for CoinWeek …..

Phoenician traders first landed in northern Tunis and founded Qart-Ḥadašt or the “New City” in the second half of the ninth century BCE. As part of a trans-Mediterranean trade network, Qart-Ḥadašt–also known as Carthage–quickly grew in importance and after several centuries grew to be one of the most powerful cities in the known world. The Carthaginians “dominated trade throughout the western Mediterranean and even into the Atlantic,” and as this new trading empire expanded, so did its currency.

The iconography of Carthaginian coins, and especially the gold denominations, was highly localized and consistent and showed little variation over the centuries. Three main images appear on these coins in various combinations: a bust of the goddess Tanit, a palm tree, and a horse.

Originating from Carthage, Tanit was an indigenous war goddess. The consort of Baal-Hamon, she was worshiped from the fifth century BCE onward. Part of her cult worship included the often debated and controversial practice of child sacrifice. Such sacrifice was not unheard of in the ancient world, but contemporary writers from Greece and Rome considered these rites “eccentric”, in the least.

The significance of the horse is a little more complicated. Noted numismatist and Carthaginian scholar Kenneth Jenkins has posited three possible interpretations. Firstly, the horse may be a symbol of Baal-Hamon, the main god of Carthage. Secondly, it may be a reference to the city’s Phoenician foundation legend, wherein a horse head was dug up from the soil on which they would build it. Thirdly, since the horse was a central part of the Carthaginian army, it may refer to the gold coinage’s military use.

Similar to the rose on Rhodesian coins, the palm tree was a mnemonic visual image representing the city. Except in rare cases, Carthaginian minting authorities employed the pairing of Tanit on the obverse and the horse on the reverse of the larger gold denominations. They reserved the palm tree and horse pair for the smaller 1/10 staters, as seen on the example below.

Since Carthage had no local sources of gold, it relied on trade with other cities and the mines in its overseas colonies.

Until Rome conquered the Iberian Peninsula in the Second Punic War (218 – 201 BCE), most Carthaginian gold came from Spanish mines. According to the Roman author Pliny the Elder, the mines of “Asturia, Gallaecia and Lusitania annually produce[ed] 20,000 pounds weight … of gold.” Roman seizure of these mines, therefore, served as a “severe military budget cut for Carthage, but a significant advantage to Rome” in the two cities’ centuries-long conflict. This “crippling” of the Carthaginian gold supply is the main reason that “no gold or silver coins were minted by Carthage immediately after the end of the Second Punic War.”

Some of this Spanish gold was struck as coins before the gold ever left Carthaginian Iberia. While the imagery is similar to contemporary Carthaginian coinage, the style is quite unique; in fact, the example below is only the second known specimen. This coin depicts a winged and laureate bust of Nike on the obverse, which, while is nearly identical to the image of Tanit on the domestic coinage, is a departure from the norm. This may be because the coin was struck by the ruling Barcid dynasty directly preceding or during the Second Punic War while they had almost complete autonomy from central Carthaginian control. It is impossible to accurately date these coins, but most agree that they were struck between 237 and 209 BCE.

Carthage also sourced gold from the west coast of Africa beyond the Pillars of Hercules. Merchants would either sail through the Straights of Gibraltar and down the coast or put together a caravan to cross the Sahara Desert, both of which were extremely dangerous journeys. Thanks to Herodotus, we have a pretty clear picture of how the trade was conducted once the merchants reached the West African tribes.

After making landfall, “the Carthaginians unload their goods, arrange them in orderly fashion along the beach, and send a smoke signal” before retreating back to their ships. The locals would then approach and “place on the ground a certain quantity of gold in exchange,” before retreating. After “com[ing] ashore and assess[ing] the gold”, the Carthaginians would determine if the quantity was fair. “If it is a fair price for their wares, they collect it and depart. If the gold seems too paltry, they go back to their ships and wait for the natives to add more gold”. According to Herodotus, this was “perfectly honest … for the Carthaginians do not touch the gold until it equals the goods’ value and the natives never touch the wares until the gold is taken”.

This passage was written by Herodotus around 450 BCE, and it is unknown how long this trade continued. However, the earliest gold and electrum coins produced by Carthage were struck in approximately 350 BCE. We can assume that they made subsequent trips since the Barcids did not capture the Iberian mines for Carthage until 241 BCE.

Like many ancient civilizations, the reach and power of the Carthaginian coinage were influenced dramatically by their fortunes in trade and war. When profiting from trade during peacetime fewer gold coins were struck. During wartime, the Carthaginian state would ramp up production and begin striking vast quantities of gold coins to help fund the war efforts and pay their mercenary armies. However, after they lost the First and Second Punic Wars their fortunes took a dramatic downturn. Not only did the gold content in the coins decrease from 98% to nearly 30%, but the style also became degraded. For example, this 1/4 stater produced near the end of the Second Punic War is highly debased and of poor style.

So overwhelming was Rome’s victory in the Second Punic War that “the only silver and gold coins struck at Carthage in the second century belong to the years of the Third Punic War”. These final Carthaginian gold coins were struck from the city’s extremely “limited” bullion supply. In fact, the ancient Sicilian-Greek author Diodorous Siculus suggested that notable Carthaginian women donated their jewelry to be melted down in order to fund the war effort after Rome laid siege to their city in 149 BCE. These rare coins are also the first and only gold serrate produced by Carthage.

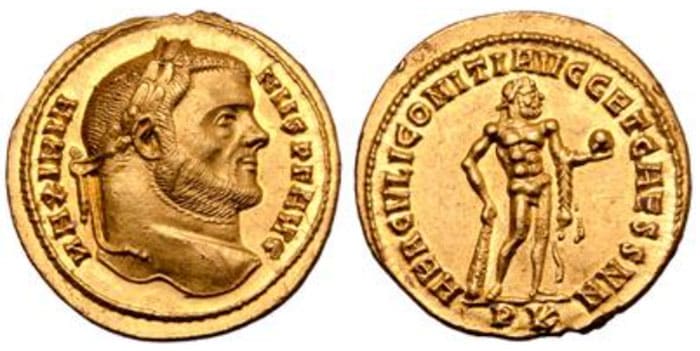

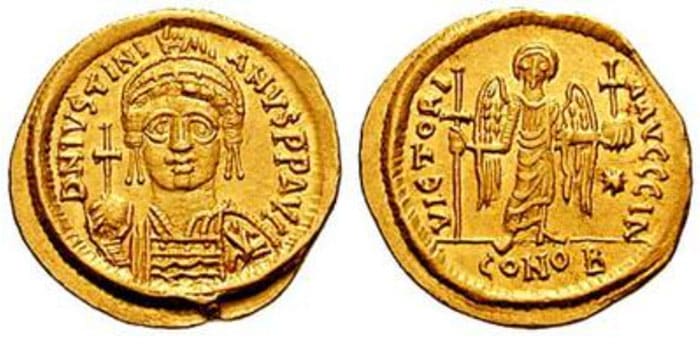

Once completely destroyed by Rome in 146 BCE, a new city was slowly built atop the ashes of the old. New Carthage lasted for the duration of the Roman Empire and the Byzantine Exarchate of Africa until the Islamic conquest seized North Africa in 647 CE. While Imperial Roman mints operated throughout this time period, most gold types were struck in the late third and early fourth centuries CE. While Byzantine authorities seemed to be more prolific, however, there were still a limited number of types struck in Carthage proper.

Happy Collecting!

* * *

Sources

https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1152&context=younghistorians

https://www2.lawrence.edu/dept/art/BUERGER/ESSAYS/PRODUCTION4.HTML

https://web.stanford.edu/dept/HPS/MayorSweatingTruthCarth.pdf

https://dcc.dickinson.edu/nepos-hannibal/carthage-early-history

https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1112&context=history_theses

https://academiccommons.columbia.edu/doi/10.7916/D8H70P28/download

https://www.academia.edu/306673/Carthaginian_Garrisons_in_Turdetania_The_Monetary_Evidence

https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/43580385.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3Adc87bee88d1769d1cdbfe3384c7ca1e4

https://www.ox.ac.uk/news/2014-01-23-ancient-carthaginians-really-did-sacrifice-their-children

Jenkins, G. Kenneth (1971-1978). “Coins of Punic Sicily, Part I-4”, Schweizerische Numismatische Rundschau.

http://digitalvirgil.co.uk/pvs/1998/part11.pdf

* * *

About the Author

Tyler Rossi is currently a graduate student at Brandeis University’s Heller School of Social Policy and Management and studies Sustainable International Development and Conflict Resolution. Before graduating from American University in Washington D.C., he worked for Save the Children creating and running international development projects. Recently, Tyler returned to the US from living abroad in the Republic of North Macedonia, where he served as a Peace Corps volunteer for three years. Tyler is an avid numismatist and for over a decade has cultivated a deep interest in pre-modern and ancient coinage from around the world. He is a member of the American Numismatic Association (ANA).