Coin Rarities & Related Topics: News and Analysis regarding scarce coins, markets, and coin collecting #395

By Greg Reynolds …..

The early silver coins of Ecuador are very rare yet not that difficult to find and acquire, as few people are collecting them in the present. From logical and historical perspectives, these are good values. The early silver coins are those minted after Ecuador became fully autonomous in 1830 and before 1863.

While the early silver coins of Ecuador are different in metallic composition and design from corresponding coins of the Spanish Empire, it was economically efficient for the denominations (the face values of the coins) of the empire to be maintained after Latin American nations became independent. For centuries, people in South America and Central America had been accustomed to the Spanish monetary system.

Before the Empire began to unravel around 1809, Spain had dominated Mexico, Central America and most of South America since the 1500s. Still, the widescale acceptance of the coins of the Spanish Empire was broader than its political reach. In the geographical area that now constitutes the continental United States, the coins of the empire were the most widely used mediums of exchange during the 1700s.

Even in New York during the 1830s, more than half the silver coins in circulation originated in Spanish-speaking societies and were of denominations of the Spanish Empire. The U.S. silver dollar was based upon the ‘Spanish Milled Dollar’, which was the Eight Reales coin of the Spanish Empire. It was often referred to as a ‘Piece of Eight’.

A Four Reales coin was a half of a Spanish Milled Dollar, essentially a half dollar. The major reason why few U.S. quarters were minted before the 1830s is that Spanish Two Reales coins widely circulated all over the United States, Mexico, Central America, South America, the West Indies and the Orient. Spanish Two Reales coins were the quarter-dollars (1/4 crowns) of the world.

Silver Content

It is curious that the early silver coins of Ecuador were specified to be two-thirds (66.67%) silver rather than at least seven-eighths (87.5%). During the last 750 years, it has been unusual for silver coins to be less than three-fourths (75%) silver.

Between 1794 and 1837, U.S. silver coins were specified to be 1485/1664 silver (89.24%). In another discussion, it was noted that the silver content of early Argentine silver coins was similar to that of early U.S. coins, seemingly about 1491/1664.

The word “fineness” refers to the precious metal content of a coin on a scale of one to one thousand, which is noted in a manner similar to the way that baseball batting averages are written. A coin that is seven-eighths (87.5%) silver, with the remainder being base metals, is 0.875 fine, though the period and initial zero are often omitted, ‘875 fine’.

From some point in 1837 to 1964, all U.S. silver coins were required to be 90% silver (0.900 fine) and 10% copper – with the exception of the first type of Three Cent Silvers, which were 750 fine (75% silver). The silver fineness of the coins of the Spanish Empire varied over time: generally 875 or higher though less than 925 (92.5%), which is the standard for ‘sterling’ silver in the British Isles.

The intrinsic value of a coin usually refers to the market value of the silver or gold in the coin, if (hypothetically) the silver or gold were removed and properly assayed. If the intrinsic value of a coin is much higher than its face value, then there is a motive to melt the coin or sell it to a firm that refines metals.

In cases where the face value of a coin was intended to be much higher than its intrinsic value by the entity that authorized the minting, then the coin is known as subsidiary or fiat coinage. The value of a subsidiary coin was wholly or partly determined by statute, decree and/or perception, rather than its value being predominantly determined by the market price of its metal content.

In reality, if a silver coin has a face value that is only slightly higher than its bullion or ‘melt value’ and it trades at face value, it is not a subsidiary coin. The difference has to be substantial. People always knew that it is costly to assay metal objects and mint coins.

The early silver coins of Ecuador, like those of Gran Colombia, were clearly subsidiary. The subsidiary or well below intrinsic value of the coins was not accidental or the byproduct of a political conflict. It was intended and planned for the face value to be much higher than the respective silver content of each coin.

Two Reales coins minted in Lima before Peru was free of royalist rule contained much more silver than Two Reales coins minted in Ecuador or Gran Colombia. Royalists loyal to Spain minted coins in Lima, Peru, until the mid-1820s. Those Two Reales coins were each 896 fine (89.6% silver) and each was minted with a net silver content of 6.0648 grams or about 0.195 Troy ounce.

In contrast, Ecuadorian Two Reales coins of the first type, which were minted in Quito from 1833 to 1836, contained from 3.45 to 3.73 grams of silver. The Spanish Empire Two Reales coins of the same region and time period each contained almost one-fifth of an ounce of silver, while the Ecuadorian Two Reales coins each contained around one-ninth of an ounce of silver. The silver content was increased for Two Reales coins of the second type (1836-41) to around one-eighth of a Troy ounce, according to my interpretation of data in Krause Publications.

There were multiple reasons for subsidiary coinage. First, the government of Ecuador was likely to have been poorly funded and probably could not afford to mint silver coins with bullion values that were close to the respective face values of the coins. Second, there was a shortage of coins in Gran Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and some nearby areas. Residents had recently been fighting revolutionary wars.

Third, if the bullion value of the silver content of each coin was close to its respective face value, coins may have been melted or taken for use in other societies. The government and people of Ecuador did not wish for businessmen and moneychangers to take their coins away and bring them far abroad.

The early silver coins of independent Ecuador were similar to those of neighboring Colombia and probably circulated at face value in Colombia, Peru and Venezuela. Pertinent information may be found in a discussion of the silver coins of Gran (‘Great’) Colombia. This was a confederation active from 1819 to the early 1830s, centered in the area that now constitutes the nation of Colombia. Ecuador and Venezuela departed from this federation in 1830.

The “Central American Republic” (CAR) was a similar confederation. The continued use of denominations of the Spanish Empire is discussed in my articles about CAR silver and the early silver coins of Argentina.

Type Coins

From the early 1830s to the early 1860s, collectible silver coins of the following denominations were struck at various times, all at the Quito Mint: Quarter-Real, Half-Real, One Real, Two Reales, and Four Reales. A Quarter-Real is 1/32 of an Eight Reales coin, and a Half-Real is 1/16. Ecuadorian Eight Reales and Five Francos coins require a separate discussion.

I am assuming that the physical data and other general information regarding these in Krause Publications is accurate. If so, the 1846 Ecuadorian Eight Reales and the Ecuadorian 1858 Five Francos coins were effectively the same denomination; these were specified to be of the same weight and fineness as French Five Francs coins of the same time period.

I am assuming that the physical data and other general information regarding these in Krause Publications is accurate. If so, the 1846 Ecuadorian Eight Reales and the Ecuadorian 1858 Five Francos coins were effectively the same denomination; these were specified to be of the same weight and fineness as French Five Francs coins of the same time period.

According to Carlos Jara, “the Ecuadorian authorities” issued a “decree” on “December 5, 1856,” which established a new monetary order “paralleling the one in France, with a coin of 5 grams with a 0.900 fineness valued at 1 Franc, or, more precisely, 1 Franco.” It is interesting that 1846 Eight Reales pieces were struck to such a standard 10 years before this decree.

Again, my primary source for coin specification data is Krause Publications. Much of this data has been republished on the NGC website.

This data suggests that Capped Bust Two Reales dated 1857 and 1862 were struck in accordance with the old standards, those that prevailed in the 1830s and ’40s. It is rather clear, however, that the new Liberty Head (Barre) design type that was introduced in 1862 corresponded to a change in weight such that the Ecuadorian Two Reales coins each had the same net silver content (4.5 grams) as one French Franc coin.

Regardless of weights, standards and purposes, Ecuadorian silver coins are appealing and fun to collect. It is not difficult to acquire type coins and representatives of a majority of dates. Early Ecuadorian coins cost less than analogous U.S. coins of similar rarity and quality.

Two Reales Coins for Beginners

Two Reales coins are appropriate for beginners and collectors who are unsure as to how much time and resources they can devote to the coins of Ecuador. Except for the last type, Two Reales type coins are fairly available. A pre-1857 type set can easily be completed and a pre-1857 date set of Two Reales coins would be a realistic quest.

The first three types of Ecuadorian Two Reales coins may be practically collected ‘by date’ without spending a great deal of money. The five design types are:

- ‘Ecuador & Colombia’ (1833-36)

- ‘Republic of Ecuador’ on Reverse (1836-41)

- ‘Republic of Ecuador’ on Obverse (1837-38)

- Capped Bust (1847-52, ’57, ’62)

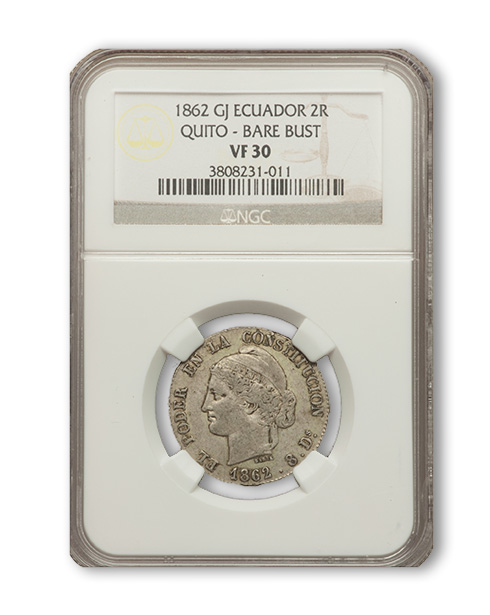

- Liberty Head (1862)

The last type is also termed ‘Barre Head’. The overall design of the Liberty Head 1862 Two Reales and Four Reales coins of Ecuador was probably the work of Albert Désiré Barre, chief engraver of the Paris Mint from 1855 to 1878. It may be true, however, that this head of liberty stems from creations by Albert’s father, Jacques-John Barre, who Albert succeeded as chief engraver.

The head on the Ceres series of postage stamps in France is credited to Jacques-John Barre and is certainly similar to the Liberty Head on 1862 Ecuadorian coins. Both father and son did engraving work for postage stamps and many numismatic items.

As for the first type of Two Reales coins, a fair question is why the legend names both Ecuador and Colombia, as Ecuador had seceded from Gran Colombia in 1830? Perhaps the idea was for Ecuadorian Two Reales coins to trade at par with Colombian Two Reales coins within both societies. The Two Reales coins stuck in Bogotá, Colombia, in 1819 and 1820 are of the same 667 silver fineness (2/3), but are a little lighter in gross weight. Later Two Reales issues in Colombia, however, are of approximately the same weight as the Ecuadorian Two Reales of 1833 to 1835.

The sun and mountains obverse is somewhat similar in design to the coins of the Central American Republic during the same time period. The 1833 is the key to the first type, ‘Ecuador & Colombia’. The 1834 is much less expensive. A well-circulated 1834 Two Reales coin could be found and acquired for well under $100.

In 2014 in Baltimore, Stack’s-Bowers auctioned a large lot of 16 Two Reales coins, which included representatives of eight dates and the first three design types. Unfortunately I did not see this lot and can therefore offer no meaningful opinion about the quality of the individual coins. Instead, the point is that 16 such coins sold for a total of $763.75 – not a vast sum for truly rare coins from the first half of the 19th century.

In September 2013 at the Long Beach Expo, Heritage auctioned an NGC-graded EF-40 1834 for $440.63. Less than two months later, Heritage sold the exact same coin for $329.

In July 2016, an 1835 “Ecuador & Columbia” Two Reales sold for $129.25. This coin is non-gradable and is in an NGC holder that indicates that it has the “details” of a Very Fine grade coin. Coins have to be seen in actuality to be evaluated. Nonetheless, the purchase of a truly rare coin, with a clear design, for $129.25 is not a risky action in the realm of coin markets.

Coins that are two-thirds silver often tone shades of deep green, which blend well with gray colors. The just-mentioned 1835 might plausibly have appealing natural toning, though this is a characteristic that cannot be discerned from pictures. While early Ecuadorian coins will tend to have understandable imperfections, it is helpful to think about degrees of originality, and to understand the colors that tend to come about on coins of particular issues.

The Two Reales type with the ‘Republic of Ecuador’ legend on the reverse dates from 1836 to 1841. In March 2011, Stack’s-Bowers auctioned an NGC-graded MS-62 1836 for $2,242. While the $2,242 result may seem to be an excessive price, a very much inferior 1836 in an NGC details holder brought $587.50 in January 2015.

A well-circulated 1836 could be purchased for less than $200. Indeed, in January 2015, Heritage auctioned a lot of 15 Two Reales coins for $1,292.50. This lot included two 1836 Two Reales coins, each with considerable detail and toning.

Ecuador is named on the obverse of the so-called “Transposed Legends” type. Heritage sold an NGC-graded VF-20 1837 Two Reales coin for $188 in November 2014. In January 2016, Heritage sold an NGC-graded Fine-12 1837 coin for $135.13.

To collectors of U.S. coins, the Ecuadorian Capped Bust type is memorable, as the bust of Miss Liberty is similar to that found on pre-1828 Capped Bust quarters and dimes. Several dates are obtainable for modest prices. While publicly available prices realized for certified coins are cited here, raw Capped Bust Two Reales coins that grade from Good-06 to Fine-15 probably can be purchased for less than $100 each.

In April 2013, Heritage sold an NGC-graded VF-25 1847 Two Reales coin for $182.13. In 2015, an NGC-graded VF-30 1848/7 overdate brought $176.25. In November 2014, Heritage sold an NGC-graded EF-45 1849 Two Reales for $270.25.

The Capped Bust Two Reales coins that were minted in 1857 and again in 1862 are often classified as a separate design type. Such a classification is incorrect, in my view. While there are differences, these are minor. The general design elements are the same as those of Capped Bust Two Reales coins that were minted from 1847 to 1852. As dates, however, the 1857 and the 1862 Capped Bust Two Reales coins are each Great Rarities.

In August 2013, Stack’s-Bowers auctioned one of fewer than five known Ecuador 1857 Two Reales coins. It is non-gradable and was in a “PCGS Genuine” holder. Perhaps it has the design detail of a VF-30 grade coin. The price realized, $7,637.50, is a substantial amount for an Ecuadorian coin, yet a small amount for a similar U.S. coin. If this coin were an 1853-O ‘No Arrows’ half dollar, it would be worth more than $125,000.

In 2014, Baldwin’s auctioned another Ecuador 1857 Two Reales. It exhibits the details of an Extremely Fine grade. It has been holed at 12 o’clock, probably to be used as a pendant or in a necklace. That same 1857 was earlier offered by Ponterio in January 2003. On September 25, 2014, that 1857 realized £2,000, then equivalent to around US$3,265.

The Liberty Head or “Barre Head” Two Reales coins constitute a one-year type. All known pieces are dated 1862. These are of the same 667 fineness (2/3 silver) as the previous issues, but are markedly heavier for the purpose of containing the same amount of silver as a French One Franc coin.

Only four of these are known.

In contrast, her sister the 1862 Four Reales coin is much less rare. An 1862 Four Reales Liberty Head (“Barre”) coin could be found for less than $500.

In contrast, her sister the 1862 Four Reales coin is much less rare. An 1862 Four Reales Liberty Head (“Barre”) coin could be found for less than $500.

Most beginners will ignore the 1862 Two Reales issue. Seeking and buying Two Reales coins from the 1830s to the 1850s is an excellent way to begin a collection of the early silver coins of Ecuador. Decent representatives of the vast majority of dates are not very expensive.

For those who continue after acquiring some Two Reales coins, building a somewhat complete type set of all denominations or a comprehensive collection of coins of the time period are practical options. It is not too difficult to assemble ‘mostly complete’ sets of Ecuadorian coins.

After beginning with Two Reales coins, Four Reales coins may be the next best choice. I myself have been drawn to 19th-century Latin American coins by their attractive designs, their exciting history, their similarities to corresponding U.S. coins, and their noteworthy rarity.

© 2018 Greg Reynolds

Greg, could you do an update on the generic gold article from 2012 with a particular focus on the number of Saint collectors: registry, type, and investment ?

I wonder if your 500 and 25,000 number for registry and type collectors has changed. I think both numbers are reasonable, but I have no idea if they are each too high or too low. Maybe talking to your dealer contacts and some trade organizations would give more details.