CoinWeek Ancient Coin Series by Mike Markowitz …..

FOR ANCIENT GREEKS and Romans, Britain was a mysterious land at the northern edge of the world.

As early as 2000 BCE, the Phoenicians traded with the Celtic tribes of Cornwall (the southwestern tip of England) for the valuable tin essential to making bronze.

By the third century BCE, coins from the Mediterranean world began to arrive in Britain, perhaps with mercenaries returning home from service on the Continent. Gold staters issued by the Belgae, imitating the widely circulated issues of the Macedonian king Philip II (reigned 359 – 336 BCE, father of Alexander the Great) entered Britain in large quantities in the second century BCE. Gold quarter staters of about 1.5 grams were the main fractional denomination.

Ancient British coinage was produced in gold, silver, and copper alloys over a period of about 150 years. It ended with the Roman conquest of Britannia by the legions of Emperor Claudius beginning in 43 CE.

Potin

Atrebates

Many ancient British coins are attributed to specific “tribes” on the basis of style and find spot. Thirty-seven different tribes are named in ancient sources but only about 10 issued coins (Rudd, 9). Some of these groups had recently migrated across the English Channel from Gaul or Belgica, and they retained close ties to their kinfolk in continental Europe. Some of these “tribes” were in the process of developing into kingdoms. The Atrebates[3] were an important Belgic group that occupied the central Thames valley.

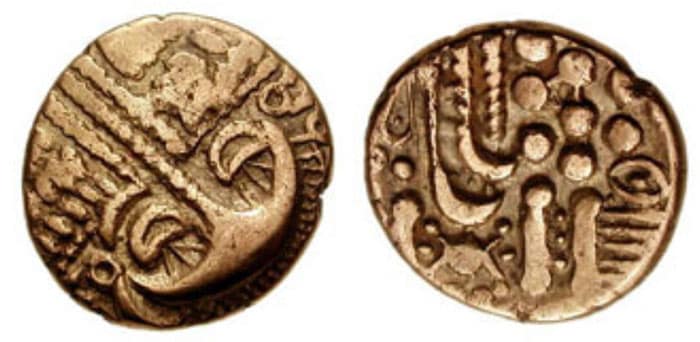

Belgae

An important group of early uninscribed gold staters – about 84 different types, dated c. 65-40 BCE – are attributed to the Belgae, who lived in the area of Hampshire on the south coast. The “Cheriton Smiler” type is named for the prominent crescent shape on the obverse, resembling a broad grin[4]. Cheriton is a village in Hampshire where the type specimen was found. Beneath the disjointed horse on the reverse is a small crab.

Dobunni

Boduoc, (c. 25 – 5 BCE) whose name means “of the battle crow” was king of the Dobunni, a tribe that inhabited the Cotswold Hills in Gloucestershire. He is only known to history from the name boldly inscribed on his rare gold staters[5].

Starfish

The Durotriges lived in the southwest of England, centered in Dorset, with their capital at Durnovaria (now Dorchester). They were seafarers, with major ports at Hengistbury Head and Poole. One of their distinctive coins was the “Badbury Starfish”, a silver piece of about 1 gram, issued c. 58 BCE – 43 CE[6]. The obverse bears a five-armed star with gracefully curved arms on a field of pellets. The abstract design on the reverse is interpreted as a thunderbolt. The common starfish (Asterias rubens)[7] is native to the waters around Britain.

Corieltauvi

The Corieltauvi (or Corieltavi, or Coritani) inhabited a broad area of the East Midlands extending from Lincolnshire into Yorkshire. Their capital, known to the Romans as Ratae Corieltauvorum, is now the city of Leicester[8]. A major hoard of 4,835 their coins, the “Hallaton Treasure”[9], was discovered in 2000.

Uninscribed silver units dated to c. 55-45 BCE feature a bristly long-legged boar and a graceful standing horse, both accompanied by prominent sun symbols[10].

Whaddon Chase

In 1849, a ploughman near the village of Whaddon in Buckinghamshire turned up a hoard of gold staters variously estimated at 450 to 2,200 pieces[11]. These handsome coins, known as Whaddon Chase staters, date to c, 55-50 BCE, during the period of Julius Caesar’s two brief invasions of Britain. A “near Mint State” example of the type sold for over $7,000 in a recent London auction[12].

Norfolk Wolf

Horses and boars are not the only beasts found on ancient British coinage.

The “Norfolk Wolf” type staters, dated c. 45 – 40 BCE, are attributed to the Iceni tribe[13]. On some examples a bird perches on the wolf’s back. The open-jawed wolf, surrounded by pellets, possibly representing the moon and stars, may stand to the right or the left.

Finney’s Thunderbolt

One of the most striking ancient British coins is “Finney’s Thunderbolt”, a very rare gold quarter stater of the Catuvellauni and Trinovantes named for a collector, Ian Finney, whose specimen now resides in the Birmingham Museum. On the obverse, a bold corded zig-zag separates two ringed pellets. On the reverse the sun, moon and stars surround a galloping horse. The type was first recorded in 1976[14].

Verica

Verica, whose name means something like “the high one”, was a son of Commios. A powerful king, he ruled over the Regini and Atrebates for 30 years (c. 10 – 40 CE.) Some of his coins, like the gold quarter stater[15], are boldly inscribed in Latin: VERIC COM F (abbreviating “Verica Son of Commios”). The use of Latin, along with Roman-inspired designs, reflects the growing influence of Rome in the years leading up to the conquest of Britain. On the reverse, the title REX (“King”) appears below a horse and seven-pointed star.

Tasciovanos

Tasciovanos, whose name means “killer of badgers”, became king of the Catuvellauni around 20 BCE, ruling from the town of Verulamium[16] (near modern St. Albans). The mint name appears as VER on many of his coins.

The example illustrated is a gold stater from my own collection, and has a special meaning for me, being the first coin I ever obtained at a major auction by bidding in person from the floor[17]. The obverse is an elaborate design of cross wreaths with hidden faces in the quarters. The reverse shows a warrior on horseback, brandishing a carnyx (a type of Celtic war trumpet.)

Cunobelin

Cunobelin is considered the primary model for Shakespeare’s Cymbeline.

Caratacus

Caratacus or Caractacus, whose name means “the beloved”, was a son of Cunobelin, born about the year 10 CE. Caratacus conquered the territory ruled by Verica, who fled to Rome and appealed for help to the emperor Claudius. Claudius used this to justify his invasion of Britain in 43 CE.

The coinage of Caratacus consists of silver “units” of about 1.3 grams (possibly based on the Roman quinarius, which was half a denarius) and tiny silver “minims” that were probably one-quarter of a unit. Some depict an eagle[18], others bear an image of the winged horse Pegasus. The ruler’s name is consistently abbreviated as CARA.

Caratacus fought a guerrilla war against the Roman legions but was eventually betrayed and captured. Sent to Rome in chains, the British chieftain made such a good impression on the Senate that his life was spared. He died in Rome around 50 CE.

The Roman historian Dio Cassius (lived c. 155-235 CE) records this story:

Caratacus, a barbarian chieftain who was captured and brought to Rome and later pardoned by Claudius, wandered about the city after his liberation; and after beholding its splendour and its magnitude he exclaimed: “And can you, then, who have got such possessions and so many of them, covet our poor tents?”[19]

Iceni

The Iceni occupied the area of Norfolk, with their capital at Venta Icenorum[20]. They were Roman allies during the conquest of Britain by Claudius, and remained nominally independent under their king Prasutagus, who died in 60 CE. His widow Boudicca[21] led a doomed revolt against Rome that was crushed in 61, becoming a legendary British national heroine. Silver units bearing the head of a spiky-haired god and a galloping horse[22] are doubtfully attributed to Boudicca’s brief reign.

Collecting Ancient Brits

A steady stream of newly discovered ancient British coins continues to emerge from the soil of England thanks to an active community of metal detector hobbyists and sensible antiquities laws[23]. The standard reference for this coinage, usually cited in auction catalog listings, is Van Arsdell (2017), which can also be found in a convenient and well-organized online version. The annual Coins of Britain and the United Kingdom provides a useful guide to prices. Ancient British Coins (2010), by Chris Rudd, is a valuable handbook for collectors.

* * *

Notes

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cantiaci

[2] VAuctions 325, June 30, 2017, Lot 4. Realized $120 USD (estimate $200).

[3] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Atrebates

[4] CNG Mail Bid Sale 66, May 19, 2004, Lot 9. Realized $1,100 USD (estimate $750).

[5] Spink Auction 15049, December 2, 2015, Lot 217. Realized £3,800 (about $5,678 USD).

[6] Roma Numismatics, E-sale 36, May 27, 2017, Lot 10. Realized £300 (about $384 USD; estimate £200).

[7] https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/wildlife-explorer/marine/starfish-and-sea-urchins/common-starfish

[8] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corieltauvi

[9] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hallaton_Treasure

[10] Roma Numismatics E sale 35, May 3, 2017, Lot 3. Realized £220 (about $284 USD; estimate £200).

[11] https://coinsweekly.com/buckingham-gold-hoard/

[12] Roma Numismatics Auction XX, October 29, 2020, Lot 1. Realized £5,500 (about $7,098 USD; estimate £3,250).

[13] Hess-Divo Auction 338, December 3, 2019, Lot 1065. Realized CHF 2,400 (about $2,433 USD; estimate CHF 1,000).

[14] Goldberg Auction 65, September 6, 2011, Lot 4007. Realized $2,300 USD (estimate $2,500-$3,500).

[15] Nomos Auction 19, November 17, 2019, Lot 3. Realized CHF 1,500 (about $1,518 USD; estimate CHF 650).

[16] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Verlamion

[17] CNG Triton XXIII, January 16, 2020, Lot 1266. Realized $1,500 USD (estimate $2,000).

[18] Spink Auction 15049, December 2, 2015, Lot 209. Realized £850 (about $1,270 USD; estimate £500-£700).

[19] https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/61*.html#33.3c

[20] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venta_Icenorum

[21] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boudica

[22] Roma Numismatic E-sale 19, August 1, 2015, Lot 3. Realized £210 (about $328 USD; estimate £100).

[23] https://finds.org.uk/treasure

References

Laing, Lloyd R. Coins and Archaeology. London (1969)

Nash, Daphne. Coinage in the Celtic World. London (1987)

Pelegero, Borja. “The Call of the Celts”, National Geographic History 7 (March/April 2021)

Rudd, Chris. Ancient British Coins. Aylsham, UK (2010)

Skingley, Philip (editor). Coins of England and the United Kingdom. London (2011)

Van Arsdell, R. D. Celtic Coinage of Britain, 3rd edition. London (2017)

* * *

Mike Markowitz is a member of the Ancient Numismatic Society of Washington. He has been a serious collector of ancient coins since 1993. He is a wargame designer, historian, and defense analyst. He has degrees in History from the University of Rochester, New York and Social Ecology from the University of California, Irvine. Born in New York City, he lives in Fairfax, Virginia.

Mike Markowitz is a member of the Ancient Numismatic Society of Washington. He has been a serious collector of ancient coins since 1993. He is a wargame designer, historian, and defense analyst. He has degrees in History from the University of Rochester, New York and Social Ecology from the University of California, Irvine. Born in New York City, he lives in Fairfax, Virginia.