By Heinz Tschachler …..

When in the early 1990s the United States was getting ready to commemorate the quincentennial of Christopher Columbus first landing on the Caribbean island of Guanahani, a bill was proposed that would eliminate the cent and the half-dollar and create a new small-dollar coin bearing a portrait of the discoverer (Wilcox, 1006-7).

Nothing ever came of this, though in November 1991 the United States Mint announced its plan for a “500 Years of Discovery Medal” for the U.S. Christopher Columbus Quincentenary Jubilee Commission. A year later, the Mint released a half-dollar commemorative coin. Designed by T. James Ferrell, the coin’s obverse shows Columbus at landfall; in the background is the Santa Maria and a smaller ship with the crew disembarking. The coin’s reverse shows Columbus’ flotilla of three ships.

The half-dollar is part of a set of three commemorative coins–a silver dollar designed by John Mercanti, which shows, on the obverse, a standing Columbus with a banner in his right hand and a scroll in his left; on the reverse, designed by Thomas D. Rogers, Sr., is a jarring juxtaposition of the Santa Maria and the Space Shuttle Discovery; a half eagle (a $5 gold coin) bears a Columbus profile bust against the eastern shoreline of the Western hemisphere on the obverse (created by T. James Ferrell) and a chart with a compass rose overlapping the western Old World with the date 1492, and Columbus’ coat of arms on the reverse (the work of Thomas D. Rogers, Sr.) (Vermeule, 206).

Emitting the coins at best was a half-hearted endeavor, done in order not to fall behind international practice (Spain, Portugal, and Italy–as well as the Bahamas, Colombia, El Salvador, Costa Rica, Cuba, Jamaica, the Dominican Republic, and other Latin American countries already had produced their commemoratives[1]).

Worse, sales figures were more than modest: of the six million pieces minted, only some 600,000 were sold to the public. Most of the coins were later melted down. The economic failure of the coin shows that in the United States there was not then much to write home about Columbus’ numismatic presence, and the 1992 commemorative did little to improve the situation[2].

The quincentennial of Columbus’ death, in 2005, did not occasion any numismatic activity on the part of the Mint, and the six-hundredth anniversary of Columbus’ birth, presumably in 1451, seems too far in the future to make any predictions.

You won’t find it in the public literature surrounding the quincentennial, but Columbus had been a popular motif on coins, currency, and medals (almost 270 altogether) in the 19th century. And beginning with Independence, he became a cultural investment throughout the new nation, an ideal founding figure visible in the arts, literature and, lest one forgets, place and event names, from the Columbia River to the World’s Columbian Exhibition in Chicago in 1892.

How, then, to explain the flagging interest in the great discoverer?

In the remainder of this essay, I will probe the following two reasons for Columbus’ decline in the American nation’s collective memory.

One, there is not a single portrait of Columbus that was taken from life. Portraits that generally passed for those of the discoverer were either pictures of his son Don Diego Columbus or purely fantasy products. Moreover, by the middle of the 19th century, the use of photographs became standard for illustrations in printed media and banknote and coin production. Increasingly, designers would think twice about using purely imaginary Columbus portraits–especially on new notes. As of the 1920s, there was no longer a place on American currency for the discoverer, whose portrait had appeared together with George Washington’s on a one-dollar note of 1869.

Two, the problem of an authentic Columbus portrait was, however, a minor issue in comparison with larger societal and cultural trends. Columbus was a Genoese in the service of the Spanish crown. By the end of the 19th century, this fact was being held against the discoverer. Strong nativist sentiments had emerged against newcomers from Southern and Eastern Europe, and concomitantly, Columbus’ status as an important figure of social cohesiveness was challenged.

And opposition to Columbus Day, which began in earnest with the quincentennial of 1892, has not gone away. As of the final years of the 20th century, the opposition, initially led by Native Americans and later expanded upon by left-leaning activists, has decried the actions taken, both by Columbus and other Europeans, against indigenous populations in the Americas. This opposition reached a new peak in June 2020, when protesters damaged Columbus statues in Richmond, Virginia; Boston, Massachusetts; and St. Paul, Minnesota.

The Problem of an Authentic Portrait of Christopher Columbus

American author Washington Irving, who in 1828 published an authoritative Columbus biography that secured the explorer’s place in narratives of America’s historical progress, had found to his chagrin that the portraits that generally passed for those of Columbus were actually portraits of Columbus’ son Don Diego.[3].

Irving then settled, half-heartedly, for a portrait painted by one Antonio Moro. The portrait, from an old volume of Italian engravings, was favored by Irving’s contacts in Spain, which included Martín Fernández de Navarrete, the author of a collection of Columbus-related documents called Colección de los viajes y descubrimientos, and the Duke of Veragua. Irving included the painting in the abridgment published by Murray of London in 1830[4].

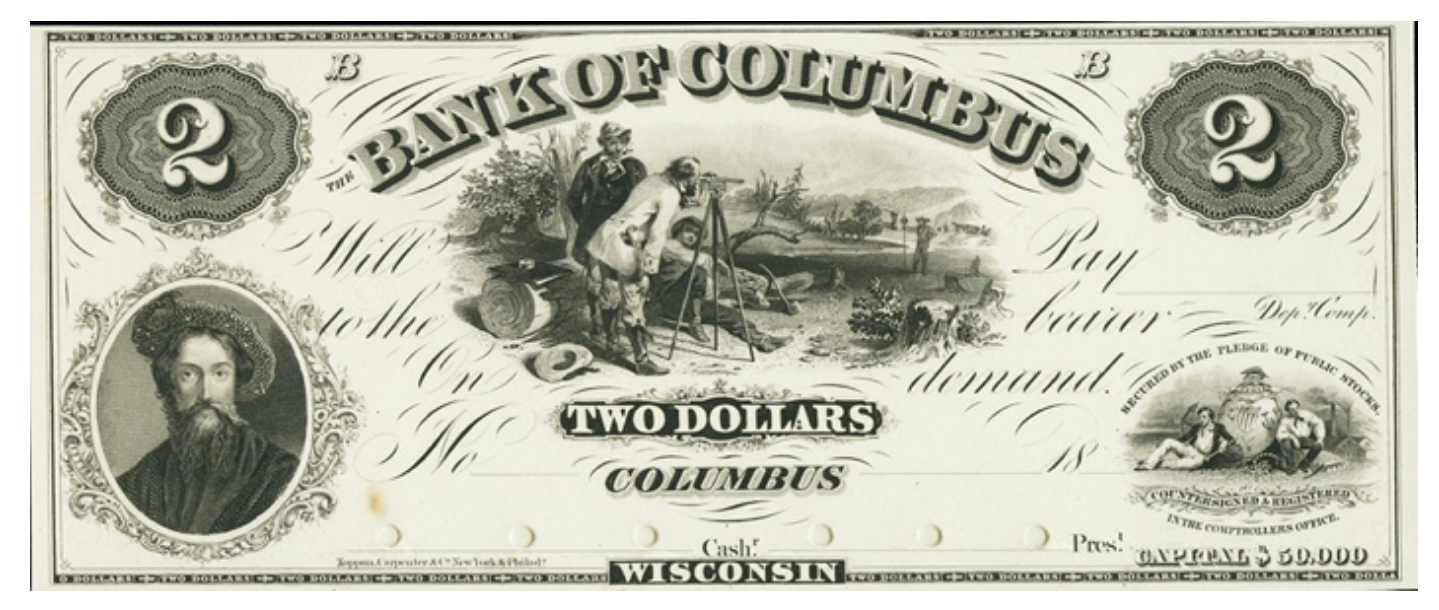

Irving’s next finding, in 1829, was a late 16th-century portrait by one Aliprando Caprioli; he had it copied but was equally unconvinced about the “authenticity of the likeness”[5].

The problem of an accurate likeness concerned Irving for the next twenty-some years.

Writing to William Cullen Bryant in December of 1851, he discusses more than half a dozen alleged Columbus portraits, though he adds a note of resignation:

“I know of no portrait extant which is positively known to be authentic.”

He finally settled for a portrait by the Spanish artist Juan de Borgoña, knowing full well that this likeness, too, might have been “purely imaginary”[6].

Depictions of Columbus on 19th-century currency notes likewise were fantasy products, including those based on a 16th-century portrait by Francesco Mazzola Parmigianino or on a 17th-century painting by Mariano Maella[7].

At the time, use of photographs had become standard for banknote production (President Lincoln’s portrait, based on Christopher S. German’s photograph, in an engraving by Charles Burt, had appeared on $10 Demand notes in 1861)[8], so why print “purely imaginary” Columbus portraits on new notes?

In the long run, Columbus gradually disappeared from currency notes.

However, as the quatercentenary of 1892 was approaching, an early 16th-century painting of a beardless man of learning, attributed to Lorenzo Lotto, was accorded something like official support, possibly because it somehow matches the description by Columbus’ second son and biographer Fernando[9]. It was thought that Lotto’s portrait of 1512, which had served for a Spanish medal, was to be the choice for the American half dollar.

Yet neither this likeness (which shows a cleanshaven man with an almost monk-like appearance who holds, in one hand, a conically projected map of Brazil) nor a plumper one by Sebastiano del Piombo was taken from life. Instead, they are thought to be copied after the sketch of an unknown artist working in Rome about 1500. A claim by the Chicago businessman C. F. Gunther that the Antonio Moro painting in his possession was the only genuine portrait of Columbus in existence was ignored.

The dilemma was resolved when the United States Mint forwarded an etching by F. Focillon, which in turn was based on a painting by Bartolomeo Suardi (aka Bramantino), in the possession of a Dr. di Orchi of Como, and hung in the Naval Museum, Madrid[10].

Also in 1892, a Henri-Emile Lefort published an etching titled Christophorus Columbus (New York: M. Knoedler, 1892). The etching, presumed to be based on an anonymous portrait in the Naval Museum at Madrid (it does look similar to the Focillon etching), was later used as the frontispiece for the Complete Works edition of Irving’s A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus[11].

Until the Civil War, depictions of Columbus on banknotes were mostly based on Parmigianino’s painting.

One reason is that once a vignette was engraved, it was offered to as many banks as possible in order to make up for the original outlay.

Gene Hessler, in “Capturing the True Columbus”, has identified bills from 10 states that used the Parmigianino portrait as a model:

- The Ansonia Bank, Seymour, CT ($5, H-CT-5-G8 and G8a, 1862)

- The Bank of America ($5, not listed in Haxby) and the Tolland County Bank, Tolland, CT ($10, H-CT-430-G64, 1840s)

- Bank of Augusta, Augusta, GA ($1, H-GA-30-G26, mid-1840s to early ’50s) and Exchange Bank, Brunswick, GA ($10, H-GA-95-G8, 1840s)

- New Orleans Canal & Banking Company, New Orleans, LA ($10, H-LA-105-G22a, late 1840s)

- Kenduskeag Bank, Bangor, ME ($5, H-ME-85-G36, late 1840s)

- Cochituate Bank, Boston, MA ($100, H-MA-130-G16, 1849 to early 1850s); Suffolk Bank, Boston, MA ($5, H-MA-370-G100 and G100b, late 1850s 1860s)

- Piscataqua Exchange Bank, Portsmouth, NH ($5, H-NH-285-G8, 1840s to ’60s)

- Bank of New Jersey, New Brunswick, NJ ($1, H-NJ-345-G2a and G20a-d, early 1850s, and see below); Somerset County Bank, Somerville, NJ ($50, H-NJ-500-G14 and G14c, 1848-1860s); and State Bank of Elizabeth, Elizabeth, NJ ($5, H-NJ-120-G40 and G40b, 1850s-1860s)

- Bank of Owego, Owego, New York ($1, H-NY-2155-G22 and G22a-d, late 1840s-’60s, and see below); Henry Keep’s Bank, Watertown, NY ($1, H-2860-G2 and G2a, 1840s); Commercial Bank of Troy, Troy, NY ($50, H-NY-2690-G28 and G28a-b, 1840s-1860s)

- Lehigh County Bank, Allentown, PA ($5, H-PA-20-G8, early 1840s) and The Miners Bank of Pottsville, Pottsville, PA ($20, H-PA-575-G32, 1840s-1850s, and see below)

- Mechanics Bank, Providence, RI ($20, H RI-340-G36, 1850s); New England Commercial Bank, Newport, RI ($2, H-RI-155-G40, 1850s); and National Bank, Providence, RI ($10, H-RI-360-G58 G58a-b, 1860s)

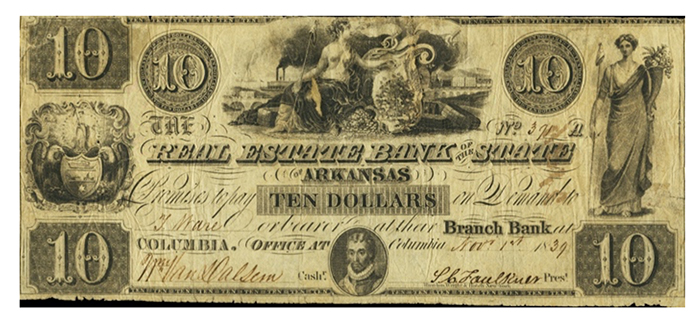

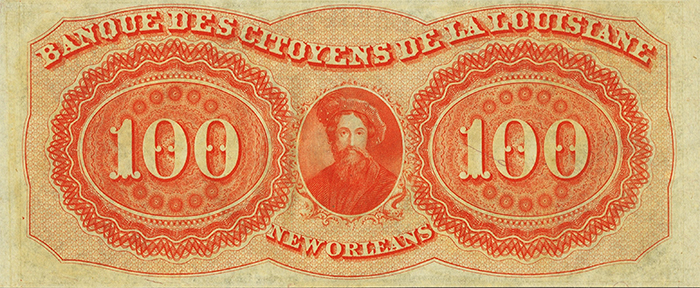

Small engravings of the so-called “Muñoz portrait“–so-named after its first appearance as the frontispiece in Juan Bautista Muñoz’ Historia del Nuevo-Mundo (Madrid, 1793)–were also used on a number of obsolete bank notes, including:

- The Real Estate Bank of the State of Arkansas, Columbia, AR ($10, H-AR-5-G32)

- The Commercial Bank of Florida, Apalachicola, FL ($2, H-FL-5-G4, 1830s)

- The Augusta Insurance & Banking Company, Augusta, GA ($100, H GA-35-G50, ca. 1828-’40s) and The Merchants and Planters Bank, Augusta, GA ($100, H GA-65-G52)

- The New Jersey Manufacturing & Banking Company, Hoboken, NJ (H-NJ-210: $1, G4 and G4a-b; $3, G26; $5, G38 and G38a; $10, G42 and G42a; $20, G44a and G46; $50, G50; $100, G54, all from the 1820s; the image is reversed on the $20, $50, and $100 notes)

- The Mississippi & Alabama Rail Road Company, Brandon, MS ($5, H-MS25-G8 and G8a-b, late 1830s)[12]

The portrait, which Mariano Maella probably painted about a century after Columbus’ death, shows a bearded man in armor and a ruff of the 17th century. Bearing no resemblance to descriptions of Columbus’ person, it is just as fanciful as others of its kind[13].

A great many currency notes bearing Columbus’ portrait came from banks that bore Columbus in their names. Early examples are $5 notes issued by the Columbiana Bank of New Lisbon, New Lisbon, Ohio, in the 1830s. The central vignette, which depicts an agrarian scene, is flanked by unidentified portraits of Columbus[14].

In the 1840s, the Columbian Bank, Boston, Massachusetts, issued Columbus notes in several denominations: the $5 notes had as their central vignette the landing of Columbus, a motif that was also used, from the late 1850s, for the $500 notes; on the $10 notes, an unidentified portrait of Columbus appears at right; the identical portrait was used, with an additional portrait of George Washington at left, for the $100 notes in the 1860s[15].

The landing of Columbus also appeared on $1 notes issued in the late 1850s by the Bank of Columbus, Columbus, Wisconsin. Other denominations from this bank also bear portraits (after Parmigianino) of the seafarer[16].

A large number of banks had “Columbia” or similar denominations as part of their names, though they did not necessarily issue notes depicting Columbus: the fraudulent, possibly non-existent Columbia Bank, Washington, D.C. (H-DC-195); The City Bank of Columbus, Columbus, Ohio (H-OH-170); the Bank of Columbus, Columbus, Georgia (H-GA-105), etc.

Still other banks had no reference to the seafarer in their names though they printed Columbus on their notes. Some of these banks have been mentioned, but prime examples, especially on account of the striking orange coloring on the back and the Parmigianino portrait in the center, were the $100 notes from the Citizen’s Bank of Louisiana (on the notes’ front a decidedly “Roman” bust of George Washington is surrounded by three scantily clad female allegories).

Less spectacular examples came from the Market Bank, Boston, MA, which in the 1830s issued $50 notes bearing an unidentified portrait of Columbus at right, with the numeral 50 above and below[17].

Also in the 1830s, the Bank of Grenada, Mississippi, and the Bank of Wilmington and Brandywine, Wilmington, Delaware, emitted $100 notes bearing as their central vignette Columbus standing, with his crew and Native Americans at a huge cross[18].

A Parmigianino portrait also graced $5 notes from the Tolwanda Bank, Tolwanda, Pennsylvania, in the 1840s. A framed Parmigianino portrait of a Renaissance-type Columbus, flanked by two females, appeared on $1 notes from the Bank of Owego, Owego, New York, during the 1840s and ’50s. The same portrait was printed on $1 notes from the Bank of New Jersey, New Brunswick, New Jersey, and the Peoples Bank, Carmi, Illinois, both in the early 1850s.

Unidentified framed portraits of Columbus also appeared on $2 notes from the Newport Bank, Newport, Rhode Island, in the 1820s and ’30s; from the Brunswick Bank, Brunswick, Maine, in the late 1840s; from the Mechanics & Traders Bank, Portsmouth, New Hampshire, the Warwick Bank, Warwick, Rhode Island, the White River Bank, Bethel, Vermont and the Bank of Brattleboro, Brattleboro, Vermont, in the 1850s; and from the Monadnock Bank, Jaffrey, New Hampshire, in the 1850s and ’60s[19].

Likewise in the 1840s, the Canal Bank, New Orleans, Louisiana, issued $10 notes bearing a Parmigianino portrait of Columbus at left, with the numeral 10 placed above and below[20].

Finally, the Boylston Bank, Boston, Massachusetts, in the 1840s and ’50s issued $10 notes with portraits both of George Washington and Christoph Columbus. Washington (flanked by a winged angel) and Columbus (after Parmigianino) were likewise put on $20 notes from the Miners Bank of Pottsville, Pottsville, Pennsylvania; in the 1860s, the Columbian Bank, Boston, Massachusetts, issued $100 notes with the identical double fare[21].

$100 notes from the Lime Rock Bank, East Thomaston, Maine, had ONE HUNDRED written across the numeral 100, with an unidentified portrait of Columbus below[22]. The identical design appeared on $100 notes from the Wrentham Bank, Wrentham, Massachusetts, in the 1840s-’50s[23].

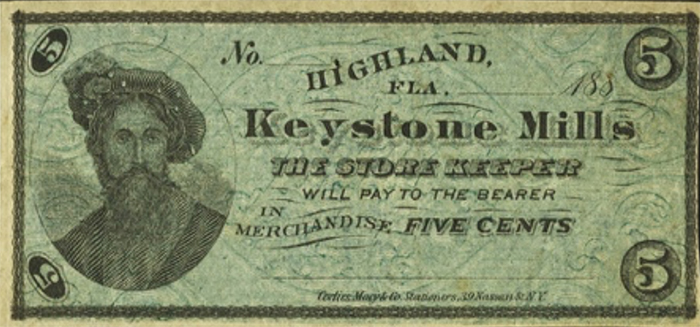

A rare fractional note, emitted by the Keystone Mills, Highland, Florida, likewise shows a Parmigianino portrait of Columbus:

After the era of private money, the new national currency–a wartime expediency–was to show scenes that would represent noteworthy events from the still-young nation’s founding history. All designs were to put as much distance between the country’s hard-won independence and its former British rule.

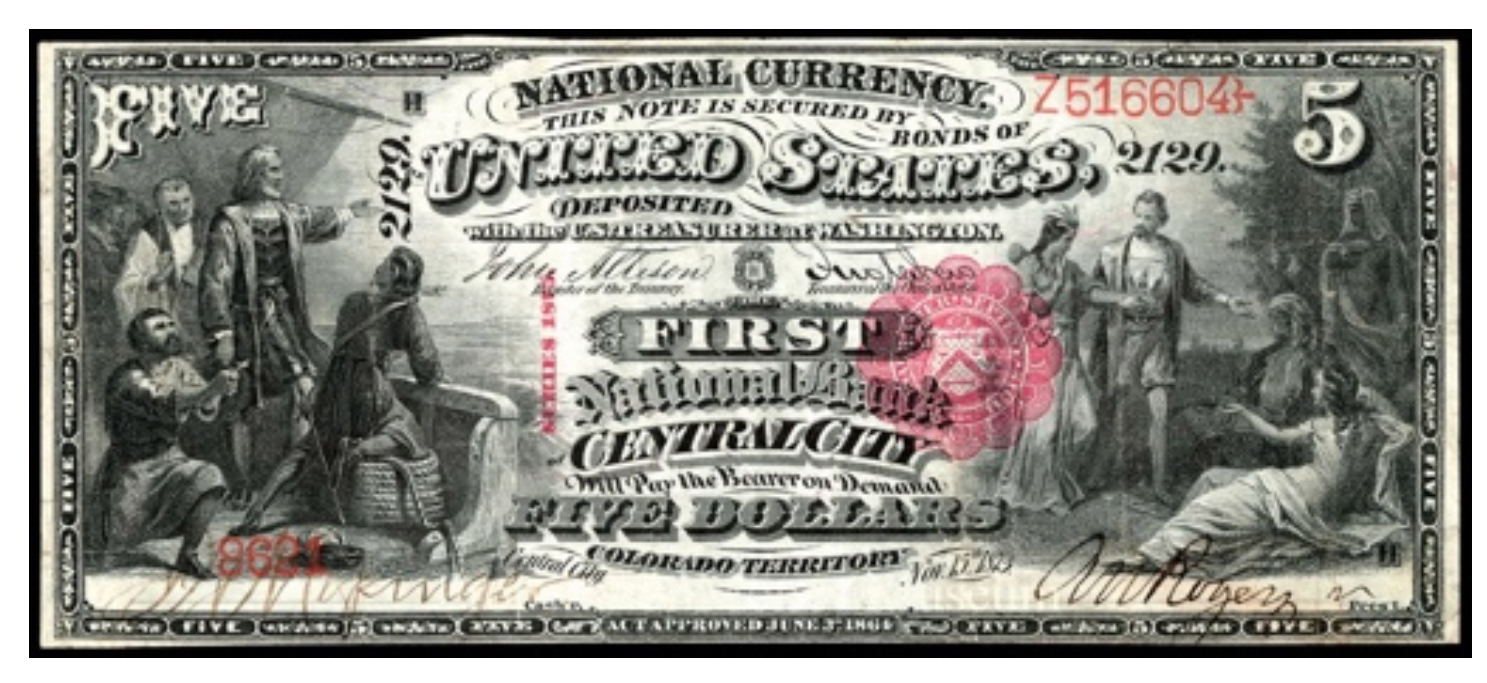

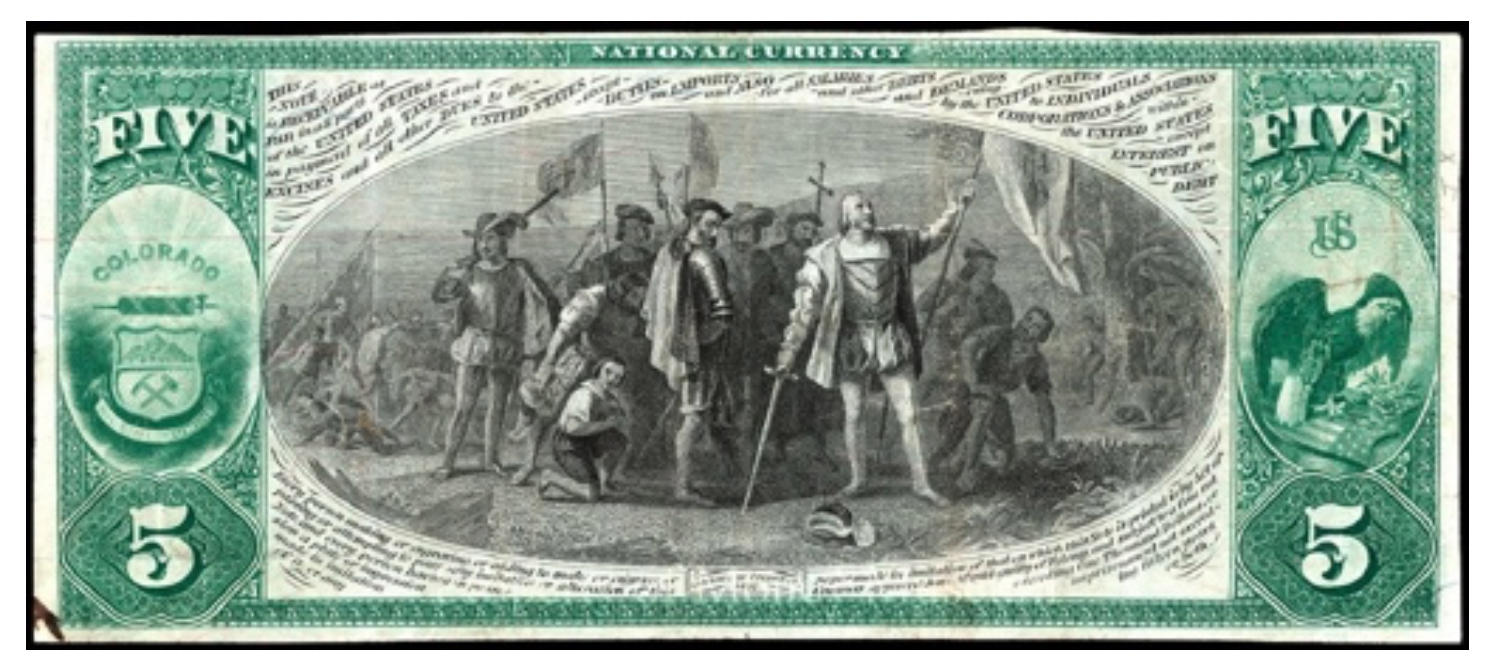

In the eyes of the authorities, Christopher Columbus symbolized the New World, not the Old. The discoverer was an ideal founding figure, and representations of him–portraits as well as historical scenes–can be found on several types of federal notes[24]. National Banknotes (and National Gold Banknotes of California) showed, in chronological order, Columbus discovering land and the landing of Columbus.

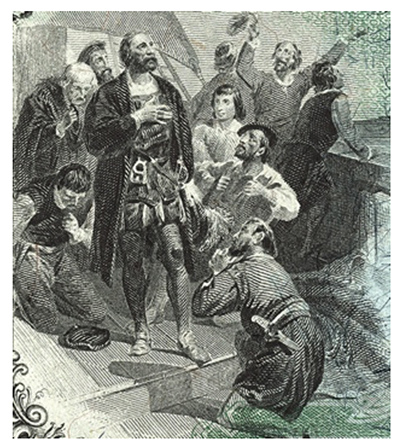

Another Columbus scene appeared on the $5 National Bank Notes, Original Series (1863-1875) and Series 1875 (1875 to 1902), and the $5 National Gold Bank Notes, Original Series. The vignette on the front is like the one on the 1869 United States note, and it is also called “Columbus in Sight of Land” (however, the engraving is by Charles Burt, after Charles Fenton’s design; more of this anon). The discovery of new land is at left. The vignette (which Louis Delnoce engraved after Charles Fenton) shows Columbus as the principal figure on deck of his caravel, thus depicting the moment of dramatic climax in the explorer’s life. At right, we see Columbus introducing America in the form of an Indian female to her three sisters of the Old World—Europe, Asia, and Africa (W.W. Rice adapted a painting by T.A. Liebler, America Presented to the Old World).

On the back of the notes is James Bannister’s version of John Vanderlyn’s The Landing of Columbus at the Island of Guanahani, West Indies, October 12, 1492, the monumental history painting from the national Capitol that shows the seafarer and discoverer standing in a triumphant pose on the beach of Guanahani, surrounded by his men[25]. The bills became tremendously popular.

However, they were counterfeited so widely (an estimated $200,000 were in circulation before the forgers were caught) that the Treasury Department initiated a design change with the Second Charter in 1882. On the new notes, Columbus was replaced by James Garfield, who had been assassinated in 1881.

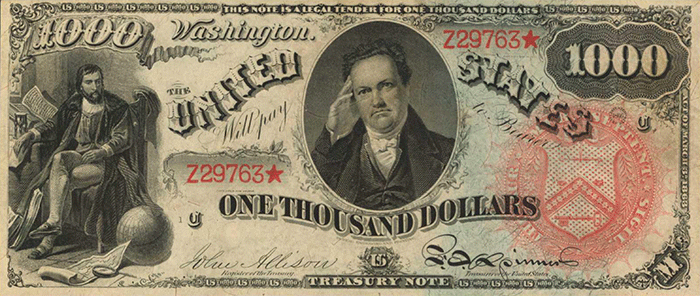

$1,000 United States notes (Series of 1869, 1878, 1880) likewise depicted Columbus. In these instances, he is shown in his study, seated, his legs crossed, and dressed in what were thought to be contemporary garments–a tunic, tights, and cloak. He is holding a piece of paper in one hand, while he contemplates the earth on the ground to his right. Next to the terrestrial globe is a map and a magnifying glass. The vignette, placed at left on the note’s face, conveys an image of learning and erudition, together with Columbus’ abilities as a navigator, his visionary courage and genius, and his conviction that the earth was not flat.

Columbus’ virtues, the note suggests, lived on in DeWitt Clinton, United States Senator, Mayor of New York City, and Governor of New York, in which capacity he was largely responsible for the construction of the Erie Canal, finished in 1825. His portrait is in the note’s center[26].

Probably the most compelling Columbus note is the $1 United States (Legal Tender) Note from 1869. Known among collectors as the “Rainbow” note because of its blue-tinted paper and colorful overprintings of red and light green, it carries a portrait of George Washington (engraved by Alfred Sealey from the famous Athenaeum painting by Gilbert Stuart) and a vignette showing Christopher Columbus in sight of land. The Columbus vignette was done by Joseph P. Ourdan after a painting by Christian (sometimes called Charles) Schussele, Columbus, Discovery of Land. It shows a bearded captain among his crew. Columbus is wearing a tunic, knee breeches, and a mantle. A few of the sailors are jubilant, if not ecstatic, pointing toward the land in the background. Others are on their knees, praying, their eyes on the captain. Columbus is depicted in an upright position, looking dignified and self-confident, his right hand over the heart. The emphasis in the representation clearly is on Columbus’ heroic character as well as on the epochal moment of discovery.

The $1 United States note of 1869 is an artistic and technical success, justly chosen for the cover of Q. David Bowers’ Whitman Encyclopedia of U.S. Paper Money. But it was its ideological message which proved tone-setting. The note’s composition—Washington’s portrait in the center, looking at Columbus at left—suggests both a chronological and a causal relationship between the face of the nation and the momentous event of October 12, 1492.

Claudia Bushman has termed this relation the “Columbus-Washington-Connection”. The “connection” constitutes the basis of a larger cultural narrative, with Columbus and Washington as the main protagonists.

Put simply, the narrative suggests that Washington became the Father of His Country because Columbus had discovered the New World for the Americans[27]. The narrative continued to be an important element in the popular imagination, as the design was kept for subsequent series, in 1874, as well as for several series from 1875 to 1917 (all with the “sawhorse reverse”, so-called because the inscription “United States of America” was set in a flattened “X” reminiscent of a sawhorse).

It also had a spectacular comeback on the back of the $5 Federal Reserve Note, series 1914, and on the Federal Reserve Bank Note, series 1915 and 1918 (on these notes, we see Columbus in sight of land at left, and the landing of the Pilgrims at right; the front is graced by a portrait of Lincoln)[28].

The arrangement, in 1869, of Founding Father of the new nation (an American of the present) and discoverer of the continent (a man of the European past) provided ideological stability and comfort for a nation that had been ravaged by the Civil War. The beginning of the “Columbus-Washington-Connection” must be sought in the War of Independence, though. Then Columbus was used to legitimize the rebellion against England, the mother country. Although the navigator himself had been convinced that he had reached India, he was nonetheless found serviceable as the protagonist of a counter-narrative against prevailing myths–of pious puritans as well as of noble cavaliers. Thus, the discoverer in the service of the Spanish kings transmogrified into an “American” hero, if not a messiah[29]. His voyages along the coasts of the Americas came to both reflect and anticipate the settlement, putatively ordained by God, by the English colonists.

Columbus was popular not just in numismatics and banknote production. He became a cultural investment throughout the new nation. As early as 1792, the Tammany Society of New York and the Massachusetts Historical Society in Boston celebrated the 300th anniversary of Columbus’ landing. Five years before, in 1787, the poet Joel Barlow published his epic poem The Vision of Columbus (it grew into the much more expansive Columbiad by 1807). William Dunlap’s play The Glory of Columbia was first performed in 1803[30]. Noah Webster’s American Spelling Book ended with two pages of important dates in American history, beginning with Columbus’ discovery of America in 1492 and ending with the Battle of Yorktown in 1781. Horatio Greenough’s 12-ton marble statue of George Washington was commissioned in 1832, the year of the centennial of the founder’s birth. Small flanking figures of an American Indian and Christopher Columbus represent the New and the Old World[31].

By 1850, three major biographies and histories of Columbus had been published, attesting to the discoverer’s prestige. The books’ authors–Washington Irving (1828), George Bancroft (1834), and William Hickling Prescott (1837)—did not see Columbus as a man of a remote past, but rather as a romantic hero and pioneer, one to help legitimate westward expansion, a harbinger of civilization and the modern era.

Irving’s History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus became spectacularly successful, especially among the general public. New editions were published almost every year until 1850, then about every two or three years. Altogether, there were about 175 editions from 1828 until 1900, some of them expressly for the use as schoolbooks[32]. And that is not counting the many translations–into Spanish, French, German, Dutch, Greek, Italian, Polish, Swedish, and Russian–made before Irving’s death in 1859.

By the time Columbus was being prepared for Irving’s Complete Works edition in 1980, the biography had seen almost 200 editions.

“Few books in modern times,” Andrew Burstein writes, “have had such a reach, or such an impact.”[33] The work, especially the one-volume abridgment of it that Irving first published in 1829, was the most popular biography of Columbus in the English language until the publication of Samuel Eliot Morison’s Admiral of the Ocean Sea in 1942[34].

Name-giving was another cultural investment.

“Columbia” had been a poetic denomination already for the North American colonies. Following the colonists’ victory at Yorktown, New York’s “King’s College” was renamed “Columbia College” (it became Columbia University in 1896). South Carolina’s new capital became Columbia. The area of the new federal capital became “Territory of Columbia”, later “District of Columbia.” There are other place names galore, such as Columbus, Mississippi, or Columbus, Ohio; and there is the Columbia River, reached by Lewis and Clark in 1805. New York’s Columbia Avenue was opened in 1892. In the same year, the World’s Columbian Exposition was dedicated in Chicago (it opened only in 1893, because of delays)[35].

On the occasion of the World’s Columbian Exposition, the United States Mint produced a half-dollar coin bearing a portrait of Columbus. It was the very first U.S. coin bearing the portrait of a historic person as well as the first official commemorative coin.

The Columbus half-dollar, of which some five million examples were struck for the Exposition, was a complete failure.

The coins would be sold for $1 each and were expected to raise some $10 million. While many were sold at the fair, countless others remained in Treasury vaults and subsequently had to be released for circulation at their face value.

Already before the coins were even designed, there had been objections. Senator John Sherman of Ohio claimed that the enormous number of the coins “would destroy their value as souvenirs.” Senator William Allison of Iowa surmised that too many “children would cry for them, and the old men would demand them,” so that the coins would be “withdrawn from circulation and fall into a condition of innocuous desuetude.”[36]

Artistically, there also is not much to write home about. Both the obverse (designed by Olin Lewis Warner and engraved by Charles E. Barber) and the reverse (created by George T. Morgan) display the academicism fostered by the Mint in Philadelphia.

The public reception too was anything but glowing. “… it will pass,” was all that the New York Press had to say, while the Boston Globe observed that to look at the coin will make one “regret that Columbus wasn’t a better looking man.” The Philadelphia Ledger noted, “If it were not known in advance whose vignette adorns the Columbian souvenir half dollar, the average observer would be undecided as to whether it is intended to represent Daniel Webster or Henry Ward Beecher.”[37]

But if the 1892 half-dollar was “a great disappointment” as a work of art, then the official medal for the Chicago fair was its exact opposite.

The obverse, the creation of no less an artist than Augustus Saint-Gaudens, who completed the design only at the fair’s closing in November 1893, shows an exuberant Columbus striding ashore on an island in the New World. Yet unlike Ourdan’s vignette on the 1869 note, on the Saint-Gaudens obverse, the other participants are kept away from the center, appearing at lower right (there are three male figures, one bearing an unfurling banner, and above are them the Pillars of Hercules [the Straits of Gibraltar] with three Spanish caravels and the inscription plus ultra, “more beyond”). The medal is dominated by a transfigured Columbus, arms extended, palms turned upward, and eyes to the sky.

With all the details centered around the powerful emotions of the discoverer, the composition becomes a complete entity, breathing, in the words of art historian Cornelius Vermeule, “mastery of the human figure over a limited area made interesting by variations in surface planes.”

Saint-Gaudens also created a reverse design, though his models were rejected–the combined result, the sculptor’s son later explained, of Victorian naughtiness and prudery. Instead, Charles E. Barber’s design was chosen for the reverse[38].

At the Chicago fair, Columbus also was commemorated through a replica of the Santa Maria anchored in the lake, a copy of the convent of La Rabida, a triumphal arch topped by a quadriga showing Columbus standing in a Roman chariot drawn by four horses, as well as any number of elongated souvenir coins and, to display the United States’ technological progress, medals and tokens made from aluminum[39].

Numismatic tributes to the quincentennial also came from around the world.

A French medal, modeled by W. Mayer after the U.S. Columbian two-cent stamp, depicts the landing on its obverse. Clad in armor, Columbus wields a sword in his right hand; a group of his fellow adventurers stands behind him. The inscription reads “Dedicated to the American People in Honor of the 400th Anniversary of the Discovery of America” and, below, “United We Stand Divided We Fall.” The reverse features a high-relief bust of Liberty encircled by stars, with the 1892 date below[40].

Another medal was produced in Milan, Italy. Known as the Milan medal, the original issue of this rare beauty was 102 mm in diameter and struck in bronze and white metal. It portrays a bust of Columbus on its obverse with allegorical figures of an Indian Princess and a draped Liberty around the sides clasping hands under a globe. The inscription “Cristoforo Colombo” surrounds the bust. The reverse shows the shields of a number of American states around a scene filled with allegorical figures. The United States Capitol at Washington and the Brooklyn Bridge can be seen in the background[41].

Questioning Columbus’ Significance

The years of the Columbian celebrations are customarily regarded as the apex of the explorer’s popularity. In 1892, 400 years after Columbus’ first voyage, President Benjamin Harrison first proclaimed Columbus Day a national holiday.

Yet 1892 also was the year when Columbus’ descent began.

Howard Kretschmar’s monumental Columbus statue at Lakefront Park (today’s Grant Park) had been unveiled with much fanfare, yet it was almost immediately considered offensive and eventually taken down, replaced by a statue of William McKinley, the martyred president.

In other respects, too, Columbus was at best the eminence grise of Chicago. Already at the fair, which was attended by more than 27 million people between May 1 and October 30, 1893, the significance of the seafarer and his discovery for the progress of the American nation was being questioned by historians like Justin Winsor, Eugene Lawrence, and Charles Francis Adams. In their wake, the discovery itself was credited to any number of individual explorers or groups—from Leif Ericson to the Portuguese to the Chinese to the Basques[42].

In themselves, these questionings were only symptoms of a deeper social conflict: the growing ethnic and cultural diversity of American society during the era of the New Immigration, 1880-1925, when some 25 million people arrived in the U.S[43]. During those years, strong nativist sentiments emerged against newcomers from Southern and Eastern Europe; concomitantly, Columbus’ status as an important figure of social cohesiveness was challenged. While the Italian community continued to claim him as their hero, his significance for the symbolic constitution of the American nation was in steady decline at the same time as an emphasis on a distinctly American past was given more and more weight.

“Emphasis on a distinctly American past” was the hidden or not-so-hidden agenda in the great currency reform of the 1920s.

The figures are impressive: between 1863 and 1929 more than 160 different types, classes, and varieties of federal banknotes were put in circulation. By 1929, the number was cut in half; as of 1930, only 15 were left. As for portraits, they were limited to those of “the Presidents of the United States”. This was the work of a special committee installed by Treasury Secretary Andrew W. Mellon, which had decided that such portraits “have a more permanent familiarity in the minds of the public than any others.”[44]

Never mind that the word “presidents” is somewhat of a misnomer, as neither Alexander Hamilton, Benjamin Franklin, nor Salmon P. Chase ever served as president. What is important is that by 1929, “all historical scenes of national significance had disappeared from American paper money and with them all depictions of Columbus’ great discovery.”[45]

Instead, the currency, the “state’s calling cards”[46], mirroring the values the state represents, such as stability, continuity, and resilience to crises, was graced by national heroes—such as Lincoln, whose portrait replaced Columbus on the $5 Federal Reserve and Federal Reserve Bank notes (until 1929, the back still showed Columbus’ landing, juxtaposed to the landing of the Pilgrims; it was then replaced by the Lincoln Memorial, which had been opened in 1922).

It is not that Christopher Columbus–or Cristoforo Colombo, as the Italians knew him–was completely eliminated from America’s cultural memory.

Columbus may have lost his status as an American national hero, but the Italian American community in particular considered Columbus’ landing as part of their heritage.

There had been private celebrations of a “Festa di Colombo” in Chicago in the 1840s, though the first public celebration was held in New York City on October 12, 1866[47]. Celebrating the achievements of the “Almirante de la Mar Océana” (the “Admiral of the Ocean Sea”, a title Columbus had received from King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, Los Reyes Católicos) continued. Columbus Day was first enshrined as a legal holiday in the United States through the lobbying of Angelo Noce, a first-generation Italian American, in Denver. Colorado governor Jesse F. McDonald proclaimed it a statewide holiday in 1905; it was made a statutory holiday in 1907. Again in 1907, a Columbus Memorial was commissioned in Washington, DC, thanks to the persistent lobbying of the Knights of Columbus.

Designed by sculptor Lorado Z. Taft of Chicago, the monument consists of a semi-circular fountain, at the center of which is a pylon crowned with a globe supported by four eagles connected by a garland. A 15-foot statue of Columbus, facing the U.S. Capitol and wrapped in a mantle, stands in front of the pylon. Flanking Columbus are two seated allegorical figures representing the Old and the New World.

The inscription reads:

“TO | THE MEMORY OF CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS | WHOSE HIGH FAITH | AND INDOMITABLE COURAGE | GAVE TO MANKIND | A NEW WORLD.”

The monument was unveiled on June 8, 1912, under the presence of President William Taft[48]. Since then, the National Columbus Day Celebration Association and the National Park Service have been honoring Columbus’ achievements by co-hosting a Columbus Day celebration at the Memorial.

The Knights of Columbus continued to be active in other avenues as well, annually emitting a medal to be sold to those joining in the parade in celebration of Columbus Day in Massachusetts. Columbus Day had been established as a holiday in that state in 1910. The 1911 medal, for instance, has a square tablet topped by a Columbus bust on its obverse; at left are the three caravels, at right a modern ocean steamer, an airplane above it, symbolic of the changed conditions of navigation. The medal’s reverse shows a laurel wreath enveloping a lighted torch, entwined with a ribbon scroll with 1492 at left and 1911 at right. Below is the inscription: COLUMBUS DAY | MASSACHUSETTS | OCTOBER 12, 1911[49].

In 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt designated the Giornata Nazionale de Cristoforo Colombo, that is, October 12, as Columbus Day. In 1966, Mariano A. Lucco, from Buffalo, New York, founded the National Columbus Day Committee, which lobbied to make Columbus Day a federal holiday. These efforts were successful, and October 12 became a federal holiday in 1968. This was changed in 1971 when Columbus Day was set on the second Monday in October (it is purely coincidental that in 2020 that day is October 12; next year’s Columbus Day will be celebrated on October 11).

Columbus Day is generally observed nowadays by banks, the bond market, the U.S. Postal Service and other federal agencies, most state government offices, many businesses, and most school districts. Actual observance, however, varies in different parts of the United States, and most states do not celebrate Columbus Day as an official state holiday. Some states, among them Hawaii and South Dakota, have replaced it with celebrations of Indigenous People’s Day.

American cities too are eschewing Columbus Day to celebrate Indigenous People’s Day. Beginning with Berkeley, CA, in 1992, the year of the quincentennial, the list now includes Austin, TX; Boise, Idaho; Los Angeles; Portland, Oregon; Seattle; and dozens of other cities. Two surveys conducted in 2013 and 2015 found that 26 to 38 percent of American adults are not in favor of celebrating Columbus Day.

Opposition to Columbus Day dates back to at least the late 19th century when anti-immigrant nativists fought its celebration because of its association with immigrants from Catholic countries, most notably Italy, as well as with the American Catholic fraternal organization, the Knights of Columbus. Anti-Catholics like the Ku Klux Klan opposed celebrations of Columbus or monuments about him because they believed that it would increase Catholic influence in the United States.[50].

But by far, the most widespread opposition began in the final years of the 20th century.

This opposition, which decries the actions taken by Columbus and other Europeans against the indigenous populations of the Americas, was initially led by Native Americans and later expanded upon by left-leaning activists. It was at a gathering of Native Americans in Davis, California, that October 12, 1992, was declared to be the “International Day of Solidarity with Indigenous People“[51].

Columbus Day celebrations and the myths surrounding the discoverer, some critics have said, only mask the ongoing actions and injustices against Native Americans. Anthropologist Jack Weatherford even declared, in 2016, that on Columbus Day, Americans celebrate “one of the greatest waves of genocide known in history.”[52]

Columbus’s character also did not escape criticism.

He was certainly a brilliant navigator, yet Columbus never hesitated to exploit and enslave the indigenous population.

Washington Irving in 1829 could still exempt Columbus from the charge of the discoverers’ “excesses”, laying the blame on his followers–villains like Roldán, Bobadilla, and Porras[53]. Norman Solomon, in Columbus Day: A Clash of Myth and History (1995), has no patience for Irving’s “double standard”, which upheld the myth of Columbus’ “sound policy and liberal views”.

Solomon quotes from Columbus’ initial description in his logbook (“They would make fine servants …”) and, at greater length, from Bartolomé de las Casas’ multivolume Historia de las Indias, which describes the discoverers as driven by “insatiable greed,” leading to “killing, terrorizing, and torturing the native peoples” with unspeakable cruelty[54]

Criticism of Columbus reached a new peak when on June 9, 2020, protesters tore down the Columbus statue in downtown Richmond, Virginia, following a peaceful demonstration outside of the statue in honor of indigenous people. The statue was ripped from its foundation, spray painted, set on fire, and subsequently thrown in a lake.

Statues of Columbus were also damaged in other places. Outside the State Capitol in St. Paul, Minnesota, protesters tied ropes around the statue’s neck and yanked it from its pedestal, while in Boston, the head of a Columbus statue was removed overnight. But these acts need to be seen in the context of the wave of protests initially set off by the murder of George Floyd.

Directed at first toward monuments to the Confederacy, the rage expanded to encompass a swath of imperialist or genocidal Europeans, including Columbus[55] Predictably, President Trump’s response has been a bellicose executive order and aggressive intimidation of people who would “impede the purpose or function” of the monuments, memorials, and statues.

The issue is more complicated, though. As Susan Tallman recently argued, it is impossible to limit public art to works “whose subjects and styles are in lockstep with our own ethics; our museums would be empty if we did.”

On the other hand, it is equally impossible to ignore the reality that “certain forms of public display act as endorsements of the values of those who erected them. Classical sculptures could only be loved by Christians once the gods they represented had died. Robert E. Lee is not yet a dead god.”[56]

Nor, of course, is Christopher Columbus.

But is Columbus Day really about the historical person? Or is it rather about the momentous, world-changing event that took place on a small island in the Caribbean on October 12, 1492?

Professor of History and Italian Studies William J. Connell thinks that the latter is the case, adding that what Columbus gets criticized for nowadays are “attitudes that were typical of the European sailing captains and merchants who plied the Mediterranean and the Atlantic in the 15th century.”[57]

While these words are hardly sufficient to assuage the anger and sense of injustice among indigenous people, it is nevertheless true that Columbus Day does not commemorate Columbus’ birthday (as was the practice for Presidents Washington and Lincoln, and as is still done for Martin Luther King, Jr.). Nor does it commemorate his death date (which is when Christian saints and martyrs are memorialized), but rather the date of his arrival in the New World.

And that, Connell adds, was precisely the intention of the people who put together the Columbus Day celebrations of 1892.

When President Benjamin Harrison in that year proclaimed Columbus Day a national holiday, praising Columbus as “the pioneer of progress and Enlightenment”, it was part of a wider effort–after the massacre by U.S. troops of about 200 Lakota Sioux at Wounded Knee on December 29, 1890 and the March 14, 1891, lynching in a New Orleans prison of 11 Italians by a mob led by prominent Louisiana politicians–to placate Native Americans and Italian Americans. President Harrison in his opening speech did not allude to either the massacre or the lynching, though he made it clear that October 12, 1892, would be a national holiday recognizing both Native Americans, who were here before Columbus, and the many immigrants–Italians included–who were just then coming to the United States in astounding numbers. It was to be a national holiday that was not about the Founding Fathers or the Civil War, but about the rest of American history, about the land and all its people[58]

During the anniversary in 1892, teachers, the clergy, poets, and politicians made use of various rituals to inculcate in people the ideals of patriotism. There were themes such as citizenship boundaries, social progress, and the importance of loyalty to the nation, brought to prominence by Francis Bellamy’s “Pledge of Allegiance”.

And there were parades.

In New York, about 12,000 public school students grouped into 20 regiments. The boys marched in school uniforms, while the girls, dressed in red, white, and blue, sat in bleachers. Also present were military drill squads and marching bands, some 5,500 students from the Catholic schools, as well as students from the private schools. These included the Hebrew Orphan Asylum, the Italian and American Colonial School, the Dante Alighieri Italian College, and the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. A college division brought together students from New York University and Columbia College (it was not yet Columbia University), who marched in white hats and white sweaters, with a message on top of their hats that spelled out “We are the People.”

For Connell, what follows from this is that “Columbus Day is for all Americans. It marks the first encounter that brought together the original Americans and future ones. A lot of suffering followed, and a lot of achievement too.”[59]

One wonders: if Columbus Day really is for all Americans, then why are some groups not part of the picture? There surely has been enough suffering loaded upon them, much as there has been achievement.

* * *

Notes

[1] See Rulau, “Numismatic Recognition of the New World, 1770-72”, 1856-58.

[2] For the sake of completeness, the American Numismatic Society (ANS) produced a tasteful medal (available in silver, lead, and bronze), which showed, on the obverse, one of Columbus’ ships mirrored in a raised globe, and, on the reverse, an American eagle hovering over the globe: http://numismatics.org/collection/1992.136.1. The St. Augustine/St. Johns County (Florida) Columbus Commission also sanctioned a medal in recognition of the quincentennial. The obverse shows Columbus’ three ships heading out to sea; the reverse features, inter alia, a portrait of Don Pedro Menendez, a Spanish soldier who founded and named St. Augustine, the oldest city in North America. See The Numismatist, October 1992, 1365-66. In fact, the American Numismatic Association (ANA) dedicated the entire issue to the quincentennial. Apart from many feature articles, the front cover showed Charles Burt’s engraving of the 1892 coin as well as the Franklin Mint’s bronze 1992 calendar/art medal. Worth mentioning is also the 1992 souvenir card program of American Banknote Commemoratives (ABNC), which included many issues featuring Columbus bank notes, stamp dies, and admission tickets to the Chicago Fair of 1893. See ibid., 1387-88, and, for an illustration of admission tickets, some of which bore a portrait of Columbus, Schefler, “The World’s Columbian Exposition,” 58. For an authoritative book about Columbian Exposition paper memorabilia, see Doolin, 1893 Columbian Exposition Admission and Concession Tickets.

[3] Irving to Lady Granard, Madrid, May 7, 1827, CW-Letters, 2:235.

[4] Ibid., and 237n9.

[5] Irving to Prince Dmitri Dolgorouki, Seville, February 4 and March 11, 1829, ibid., 2:377- 78, 388; see also Irving’s letter to John Murray, his publisher, of February 14, 1829, ibid., 383.

[6] Irving to Bryant, December 26, 1851, ibid., 4:283. See a. Irving’s lengthy letter to Bryant of December 20, 1852, in Pierre M. Irving, The Life and Letters of Washington Irving, 4:93-96, as well as Ben Harris McClary, Washington Irving and the House of Murray (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1969), 115, and John Boyd Thacher, Christopher Columbus, His Life, His Work, His Remains, 3 vols. (1903-1904; repr. New York: AMS Press; 1967), 1:69- 70.

[7] Vermeule, Numismatic Art in America, 87-88, 230, and Hessler, “Capturing the True Columbus,” 1436-39. In the late 1850s, the “Parmigianino” Columbus was identified as the condottiere Galeazzo Sanvitale of Fontanello, Province of Parma:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:(formerly_thought_to_be)_Christopher_Columbus, _1451_-_1506_RMG_RP6231.jpg. For a fanciful illustration by F. O. C. Darley for a projected illustrated volume of Irving’s Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, see The Worlds of Washington Irving, 54; the drawing, which shows a hardened and warlike Columbus kneeling on the beach of Guanahani, is available from the New York Public Library, Manuscript and Archives Division in the Duyckinck, Hellman, Seligman’s collections and Washington Irving Papers.

[8] Tschachler, The Greenback, 111.

[9] “The Admiral was a well-built man of more than average stature, the face long, the cheeks somewhat high, his body neither fat nor lean. He had an aquiline nose and light-colored eyes. His complexion too was light and tending to bright red. In youth his hair was blond, but when he reached the age of thirty, it all turned white.” Ferdinand Columbus, The Life of the Admiral Christopher Columbus by His Son Ferdinand, 9.

[10] Vermeule, Numismatic Art in America, 87-88, 230, and Curtis, Christopher Columbus, item 25; for a different genealogy of the portrait used for the Columbian half dollar, see Schefler, “The World’s Columbian Exposition,” 55-56. The Musei Civici di Como, Italy, also holds a portrait by an unknown artist, which is similar to but not identical with the Lotto portrait; and it is dated 1516: http://www.cristoforocolombo.com/ritratti-co lombo/ritratto-cristoforo-colombo-anonimo-ai-musei-civici-como/, accessed September 15, 2020.

[11] See Irving, CW-Columbus, viii, and view the etching at the Library of Congress: https://www.loc.gov/resource/pga.02005/, accessed June 29, 2020. For more on Columbus por traits, see Lester, “Looks Are Deceiving”, 221-27, Annaloro, “Man of Mystery”, 33 (both on the Lotto portrait), and Oliver and Kelly, “Columbus Controversy”, 98-99.

[12] Hessler, “Capturing the True Columbus”, 1,439. Haxby in his Standard Catalog of United States Obsolete Bank Notes (2:1113) mistakenly identified the portrait on the notes from the Mississippi & Alabama Rail Road Company as Fernando de Soto’s.

[13] Maella’s original was in the possession of the Duke of Veragua, a descendant of Columbus. Veragua did not think much of the Muñoz, favoring, in his correspondence with Washington Irving, the Antonio Moro portrait. A copy of the Muñoz hangs in the Archives of the Indies at Seville. Another copy was presented to the Philadelphia Academy of Arts in 1818 but disappeared a few years later and has remained untraceable. “Report of the United States Commission to the Columbian Historical Exposition at Madrid, 1892-1893”, 237. https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=ucm.5325305690&view=1up&seq=10

[14] Haxby, OH-320-G40.

[15] Haxby, MA-140-G66, G-122, G-84, and G-118.

[16] Haxby, WI-95-G2, G2a, and R5 ($3b notes raised from the G2 series); for the $2 notes, see G4, G4a, and R7 ($5 notes raised from the G4 series).

[17] Haxby, MA-265-G50.

[18] Haxby, MA-265-G50, MS-80-G20 and DE-85-G56; for good illustrations, see Bowers, Whitman Encyclopedia of Obsolete Paper Money, 7:399 and 8:46. Another bank issuing notes with the identical vignette was the Farmers Bank of the State of Delaware, Dover, Delaware (Haxby, DE-15-G90a and G90b).

[19] Haxby, PA-650-G4, NY-2155-G22, G22a through G22d, NJ-345-G2a, G20a and G20b, IL-115-G2, RI-160-G20 (illustration in Bowers, Whitman Encyclopedia of Obsolete Paper Money, 5:88), ME-125-G8, NH-265-G10, RI-545-G30 (illustration in Bowers, Whitman Encyclopedia of Obsolete Paper Money, 5:288), VT-20-G8 (illustration ibid., 5:326), VT35- G24, and NH-135-G6 and G6b. $5 notes from the City Bank of Troy, Troy, New York, also bore the identical vignette (Haxby-NY-2735-G36 and G36a-b, 1840s-’60s), as did $20 notes from the Mechanics Bank, Providence, RI (Haxby, RI-340-G36, 1850s).

[20] Haxby, LA105-G20.

[21] Haxby, MA-120-G10, PA-575-G32, MA-140-G118 (illustration in Bowers, Whitman Encyclopedia of Obsolete Paper Money, 3:90).

[22] Haxby, H-ME-275-G72.

[23] Haxby, MA-1335-G86.

[24] Altogether, between 1863 and 1929, four different representations of Columbus and his landing appeared on five types of federal currency, in 14 different series. For an overview of the development of America’s paper money since the Civil War, see Lauer, “Money as Mass Communication”, 121–24.

[25] Vanderlyn’s painting was inspired by the description of the landing in Washington Irving’s biography. Loock, “Goodbye Columbus, Hello Abe!”, 87-89 and for illustrations, Friedberg and Friedberg, Paper Money of the United States, 80, 332, 339, and Bowers, Whitman Encyclopedia of U.S. Paper Money, 217, 219, and 223.

[26] Loock, “Goodbye Columbus, Hello Abe!”, 86; for illustrations and brief descriptions, see Friedberg and Friedberg, Paper Money of the United States, 32-33, 325, and Bowers, Whitman Encyclopedia of U.S. Paper Money, 734-37.

[27] Bushman, America Discovers Columbus, 53. On the “Columbus-Washington-Connection” on the national currency, see Loock, “Goodbye Columbus, Hello Abe!”. On Columbus’ influence on the rewriting of America’s national origin myth, see Kubal, Cultural Movements and Collective Memory.

[28] Bowers, Whitman Encyclopedia of U.S. Paper Money, 111-16 (for the $1 notes), 253-61 (for the Federal Reserve notes), and 262-65 (for the Federal Reserve Bank notes).

[29] On Columbus as an American “messiah”, see Boorstin, The Discoverers, 232.

[30] Smorag, “From Columbia to the United States of America”, 74-75, and Schlereth, “Columbia, Columbus, and Columbianism”, 937-68.

[31] Greenough’s statue was on display in the Capitol Rotunda from 1841 to 1843, when it was relocated to the east lawn. In 1908 Congress transferred the statue to the Smithsonian Institution, where it was exhibited in the Smithsonian Castle until its relocation to the new National Museum of American History in 1964. It has resided on the second floor of the Museum ever since. When the Museum reopened November 21, 2008, the Washington statue became the signature artifact for a section in the west wing of the museum focused on American lives. National Museum of American History, “Landmark Object: George Washington Statue, 1841.”

[32] According to Andrew Burstein, Irving’s Columbus generally was “the most commonly owned book” in American libraries in the mid-19th century and “undeniably influenced how American school-children were taught their country’s origins.” Burstein, The Original Knickerbocker, 196. For the 1833 recommendation by the New York State Legislature that Irving’s Columbus be used as a textbook for the common schools, see Myers, The Worlds of Washington Irving, 73.

[33] Burstein, The Original Knickerbocker, 205.

[34] On the popularity of Irving’s Columbus, see a. Williams, Life of Irving, 1:355, 2:304.

[35] For a history of the fair, see Larson, The Devil in the White City, and Loock, Kolumbus in den USA, 85-91, 118-39.

[36] Schefler, “The World’s Columbian Exposition”, 55-56, quotations 55.

[37] All press comments qtd. in The Numismatist, January 1943, 20.

[38] Vermeule, Numismatic Art in America, 90-92, quotation 90. Saint-Gaudens had rendered a nude male youth representing the Spirit of America in his initial design for the reverse. Both this and two more proposals were turned down. Instead, Charles E. Barber’s uncontroversial (and cluttered) design was selected. The decision infuriated Saint-Gaudens, who later savaged Barber’s accepted design.

[39] Virginia Culver, “The Medal Collectors’ Corner”, The Numismatist, July 1968, 395. For an illustration of the quadriga, see Loock, Kolumbus in den USA, 131.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Medals from recut dies and a new obverse were 59 mm in diameter and were struck in bronze, white metal, and aluminum. The new obverse deleted the allegorical figures around Columbus’ bust, “Cristoforo” was anglicized to “Christopher”, and the inscription around the rim became “Memento of the World’s Fair, Chicago 1893”. Culver, “The Medal Collectors’ Corner”, 395.

[42] Loock, Kolumbus in den USA, 348-51 and 361-81.

[43] Higham, Strangers in the Land, 64-65, 87-96.

[44] United States Bureau of Engraving and Printing (USBEP), “U.S. CURRENCY FAQs”. On the currency reform, see Tschachler, George Washington on Coins and Currency, 123-28.

[45] Loock, “Goodbye Columbus, Hello Abe!” 91.

[46] Deutsche Bundesbank, “Das besondere Objekt” [“The Special Object”], web document: Not simply “ein Gegenstand des täglichen Gebrauchs für jedermann … als Werbeträger sollte sie ein Spiegelbild der Werte sein, die sie repräsentiert, wie Stabilität, Kontinuität und Krisenfestig keit. […] Daher wird die Banknote gelegentlich auch als Visitenkarte eines Staates bezeichnet.”

[47] In this and the following paragraphs I have drawn on Loock, Kolumbus in den USA, 244-45, 309-45.

[48] See Schenkman, “Mementoes of the Columbus Memorial”, 75.

[49] For further details, see Anon., “A Columbus Day Medal”, 207.

[50] Loock, Kolumbus in den USA, 23-37.

[51] As if in (a somewhat awkward) response to the declaration, American schoolchildren designed a pattern dollar showing a bust of Columbus on the obverse and an Indian head and tree on the reverse: http://numismatics.org/collection/1992.13.1?lang=en.

[52] Weatherford, “Examining the Reputation of Christopher Columbus”, web document; the article originally appeared in the Baltimore Evening Sun on October 20, 2016.

[53] Irving, History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, CW-Columbus, 353.

[54] Solomon, “Columbus Day: A Clash of Myth and History”, (1995). References to Irving’s “double standard” and Columbus’ purportedly “sound policy and liberal views” are to Hazlett, “Literary Nationalism and Ambivalence in Washington Irving’s The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus”, 567.

[55] NBC12 Newsroom, “Christopher Columbus Statue torn down, thrown in lake by protesters”, and Johnny Diaz, “Christopher Columbus Statues in Boston, Minnesota and Virginia Are Damaged”.

[56] Tallman, “Who Decides What’s Beautiful?”, 16, 20.

[57] Connell, “What Columbus Day Really Means”.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Ibid.

Bibliography

Annaloro, Victor. “Man of Mystery”, The Numismatist (October 2004): 33.

Anon. “A Columbus Day Medal”, American Journal of Numismatics 45 (1911): 207.

Boorstin, Daniel J. The Discoverers. New York: Random House, 1983.

Bowers, Q. David. Whitman Encyclopedia of Obsolete Paper Money. 8 vols, to date. Atlanta, GA: Whitman, 2014-.

———. Whitman Encyclopedia of U.S. Paper Money. Atlanta, GA: Whitman, 2009.

———. Obsolete Paper Money Issued by Banks in the United States, 1782-1866. Atlanta, GA: Whitman, 2006.

Bundesbank, Deutsche. “Das besondere Objekt” [“The Special Object”]. November 24, 2010. Web. December 2, 2014.

Bushman, Claudia L. America Discovers Columbus: How an Italian Explorer Became an American Hero. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1992.

Columbus, Ferdinand. The Life of the Admiral Christopher Columbus by His Son Ferdinand. Trans. Benjamin Keen. New Brunswick, NJ: Greenwood Press, 1959. Spanish edn. Historia del almirante Don Cristóbal Colón … [1604], 2 vols. Madrid: T. Minuesa, 1892.

Connell, William J. “What Columbus Day Really Means”, The American Scholar. October 4, 2012. Web. February 13, 2017.

Culver, Virginia. “The Medal Collectors’ Corner”, The Numismatist (July 1968): 395.

Curtis, William Elroy. Christopher Columbus: His Portraits and His Monuments. Chicago: Lowdermilk, 1893. Internet Archive, 2014. September 15, 2020.

Diaz, Johnny. “Christopher Columbus Statues in Boston, Minnesota and Virginia Are Damaged“, The New York Times, June 10, 2020, updated July 24, 2020. Web. September 26, 2020.

Doolin, James. 1893 Columbian Exposition Admission and Concession Tickets. Dallas, TX: Doolco, 1981.

Eglit, Nathan N. Columbiana: The Medallic History of Christopher Columbus and the Columbian Exhibition of 1893. Chicago: Hewitt Brothers, 1965.

Friedberg, Arthur L., and Ira L. Friedberg. Paper Money of the United States. 16th Edition. Clifton, NJ: The Coins and Currency Institute, 2001.

Haxby, James A. Standard Catalog of United States Obsolete Bank Notes, 1782-1866. 1988. 4 CD-ROMS. Iola, WI: Krause Publications, 2009.

Hazlett, John D. “Literary Nationalism and Ambivalence in Washington Irving’s The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus”, American Literature 55.4 (1983): 560-75.

Hessler, Gene. “Capturing the True Columbus”, The Numismatist 105:10 (October 1992): 1436-39.

Higham, John. Strangers in the Land: Patterns of American Nativism, 1860-1925. 1955; New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1988.

Irving, Pierre M. The Life and Letters of Washington Irving, 4 vols. New York: Putnam, 1862-1864.

Irving, Washington. The Complete Works of Washington Irving: The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus. Ed. John Harmon McElroy. Boston: Twayne, 1981. Abbrev. as CW-Columbus.

———. The Complete Works of Washington Irving: Letters. Ed. Ralph M. Aderman, Herbert L. Kleinfield, and Jenifer S. Banks. 4 vols. Boston: Twayne, 1978-1982. Abbrev. as CW-Letters.

Kubal, Timothy. Cultural Movements and Collective Memory: Christopher Columbus and the Rewriting of the National Origin Myth. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. Larson, Erik. The Devil in the White City: Murder, Magic, and Madness at the Fair that Changed America. New York: Crown Publishers, 2003.

Lauer, Josh. “Money as Mass Communication: U.S. Paper Currency and the Iconography of Nationalism.” The Communication Review 11 (2008): 109–32.

Lester, Paul Martin. “Looks Are Deceiving: The Portraits of Christopher Columbus.” Visual Anthropology 5 (1993): 221-27.

Littleton Coin Company. “Discovering Christopher Columbus on Coins and Currency.” October 2018. Web. August 27, 2019.

Loock, Kathleen. “Goodbye Columbus, Hello Abe! – Changing Imagery on U.S. Paper Money and the Negotiation of American National Identity”, Almighty Dollar: Paper and Lectures from the Velden Conference. Ed. Heinz Tschachler, Eugen Banauch, and Simone Puff. American Studies in Austria, Vol. 9. Wien-Münster: LIT Verlag, 2010. 81-101.

———. Kolumbus in den USA: Vom Nationalhelden zur ethnischen Identifikationsfigur. Bie lefeld, Germany: Transcript Verlag, 2014.

Myers, Andrew B. The Worlds of Washington Irving, 1783-1859. Tarrytown, NY: Sleepy Hollow Restorations, 1974.

National Museum of American History. “Landmark Object: George Washington Statue, 1841.” N.d. Web. February 27, 2017.

NBC12 Newsroom. “Christopher Columbus Statue torn down, thrown in lake by protesters.” June 10, 2020. Web. September 17, 2020. https://www.nbc12.com/2020/06/09/christopher-columbus-statue-torn-down-thrown-lake-by-protesters/.

Oliver, Nancy, and Richard Kelly. “Columbus Controversy”, The Numismatist 126:11 (November 2013): 98-99.

“Report of the United States Commission to the Columbian Historical Exposition at Madrid, 1892-1893”, The Executive Documents of the House of Representatives for the Third Session of the Fifty-Third Congress, 1894-1895, vol.31 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1895).

Rulau, Russell. “Iconography: Numismatics”, The Christopher Columbus Encyclopedia. Ed. Silvio A. Bedini. 2 vols. Basingstoke, UK: Macmillan, 1992. 1:325-27.

———. Discovering America: The Coin Collecting Connection. Iola, WI: Krause, 1989.

———. “Numismatic Recognition of the New World”, The Numismatist (November 1989): 1768-72 and 1856-59.

Schefler, Erik. “The World’s Columbian Exposition: A Fair of Firsts”, The Numismatist (June 2011): 54-58.

Schenkman, David E. “Mementoes of the Columbus Memorial”, The Numismatist (July 2003): 75-76.

Schlereth, Thomas J. “Columbia, Columbus, and Columbianism”, Journal of American History 79 (December 1992): 937-68.

Smorag, Pascale. “From Columbia to the United States of America: The Creation and Spreading of a Name”, American Foundational Myths. Ed. Martin Heusser and Gudrun Grabher. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag, 2002. 67-82.

Solomon, Norman. “Columbus Day: A Clash of Myth and History” (1995). Archived in WebArchive.org. October 8, 1998. September 20, 2020.

Tallman, Susan. “Who Decides What’s Beautiful?”, The New York Review of Books LXVII, Number 14 (September 24, 2020): 16-20.

Tschachler, Heinz. George Washington on Coins and Currency. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2020.

———. The Greenback: Paper Money and American Culture (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2010.

United States Bureau of Engraving and Printing (USBEP). “U.S. CURRENCY FAQs.” N.d. Web. July 7, 2014.

Vermeule, Cornelius C. Numismatic Art in America: Aesthetics of the United States Coinage. 2nd edn. Atlanta, GA: Whitman, 2007.

Weatherford, Jack. “Examining the Reputation of Christopher Columbus“, Documents of Taino History and Culture. N.d., September 20, 2020.

Wilcox, Rick. “Columbus Not Appropriate for Proposed Dollar Coin”, The Numismatist (July 1991): 1006-1007.

Williams, Stanley T. The Life of Washington Irving. 2 vols. New York: Oxford University Press, 1935.

* * *

Fascinating, impressively researched piece, but I think the author would have benefited from reading (if he did not) Brent Staples Oct. 12, 2019 NYTimes article “How Italians Became ‘White,'” which explains the origins of the 1892 proclamation of Columbus Day. To quote the author: “Few who march in Columbus Day parades or recount the tale of Columbus’s voyage from Europe to the New World are aware of how the holiday came about or that President Benjamin Harrison proclaimed it as a one-time national celebration in 1892 — in the wake of a bloody New Orleans lynching that took the lives of 11 Italian immigrants. The proclamation was part of a broader attempt to quiet outrage among Italian-Americans, and a diplomatic blowup over the murders that brought Italy and the United States to the brink of war.”

“Historians have recently showed that America’s dishonorable response to this barbaric event was partly conditioned by racist stereotypes about Italians promulgated in Northern newspapers like The Times. A striking analysis by Charles Seguin, a sociologist at Pennsylvania State University, and Sabrina Nardin, a doctoral student at the University of Arizona, shows that the protests lodged by the Italian government inspired something that had failed to coalesce around the brave African-American newspaper editor and anti-lynching campaigner Ida B. Wells — a broad anti-lynching effort.”

The lynching referenced was one in which 19 Italian immigrants were falsely accused or murdering the New Orleans police chief despite any evidence they were involved or any trial. During the 19th century largely because as the author of this piece explains, Italian immigrants from southern Italy were grouped with black Americans as dark-skinned people, there were many other incidents of them being lynched due in good part to the spreading of racist stereotypes by papers like the NYTimes.

11, not 19, Italian immigrants.

The Problem of an Authentic Logbook

It is most certainly worthwhile pointing out the lack of any extant portrait of Columbus when discussing how he has been depicted on currency, etc. At the same time, it is probably also just as important to point out the lack of any extant logbook when discussing him as a historical figure. For example, Norman Solomon could not have actually taken direct quotes from logbooks that did not exist. What exists are transcriptions, some of which, at least, were translated into other languages and were, therefore, quite possibly subject to some degree of interpretation. Consequently, we can never really know how accurate our understanding is of how he looked or what he wrote, and the reason is the same in both instances.

What an excellent article. I love coins for many reasons, one of them being that they take you through time and there’s a story for each. Whether an empire, kingdom, city state, or whatnot. Coins are also a great place to immortalize great people and places. The Age of Discovery is a perfect era that coins can use to highlight and educate.

It’s shameful that we portray Columbus and other explorers who took great risk and expanded our knowledge and world as one-dimensional villains. It’s not as if native Americans lived in blissful peace until Europeans showed up. There was near-permanent war, genocide, slavery, mutilation, and ritual sacrifice. When Columbus landed in the Caribbean, the Arawak asked him for protection from the Carib people, who slaughtered and ate them. When Cortez landed in what is now Mexico, the people living there saw him as a savior who could free them from the Aztecs who had conquered and enslaved them. The Aztecs, Inca, and Maya all practiced large-scale human sacrifice.

So without downplaying the other side of the story, let’s not outright pretend none of the items I mentioned happened either. Unfortunately you can’t say any of this nowadays because actual debate and facts are just inconvenient and need to be instantly canceled and shut down.